|

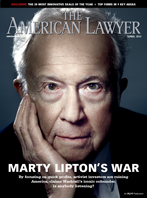

Marty Lipton's War on Hedge Fund

Activists

Michael D. Goldhaber, The

American Lawyer

March 30, 2015

Steven Laxton |

In November 2012, the corporate law guru who is most revered by

managers faced off against the corporate law guru who is most feared

by managers, at the Conference Board think tank in New York, in a

friendly debate that was about to turn hostile. Martin Lipton has

defended CEOs against all comers since forming Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen

& Katz 50 years ago. Lucian Bebchuk, a Harvard Law School professor,

champions the "activist" hedge funds that assail CEOs in an

intensifying struggle for control of America's boardrooms.

Speaking with a thick Israeli accent ("Vock-tell is wrong"), Bebchuk

argued that shareholder activism helps companies in both the short and

long term. Lipton, whose voice carries a trace of Jersey City ("The

bawd is right"), countered that activism is awful for companies and

the economy over the long run. "Nor do I accept [your] so-called

statistics," said Lipton fatefully. "Your statistics are all based on

things like 'What was the price of the stock two days later?'"

As Lipton finished the thought, Bebchuk twitched his foot. He unfolded

his right leg over his left knee, and then reset his body. He licked

his lips, pressed the button of an imaginary pen with his thumb, then

lunged for a pad and started scribbling with a real one. Thus was born

"The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism," the paper that turned

a genial debate into a nasty war over the direction of corporate

America. (It's to be published in June by the Columbia Law Review.)

At 83, Lipton is a blue chip stock. He's one of two people to make

every list of the 100 Most Influential Lawyers in America since it was

launched by the National Law Journal 30 years ago. (The other is

Beltway legend Thomas Hale Boggs Jr., who died last September, just

months after ailing Patton Boggs merged with Squire Sanders.) Wachtell

Lipton remains The Am Law 100's runaway leader in profits per partner,

as it has been for 15 of the past 16 years.

Lipton is most famous as the inventor in 1982 of the "poison pill"

defense to corporate takeovers, which enables a company to dilute the

value of its shares when a hostile bidder draws near. He's also

heavily identified with the "staggered board," which deters takeovers

by spreading the election of a board's directors over several years.

It's often forgotten that Lipton helped to pioneer the concept of the

corporation that undergirds corporate social responsibility. In his

seminal 1979 work, "Takeover Bids in the Target's Boardroom," Lipton

argued that directors should protect the interests of not only

shareholders, but all who have a stake in the company: creditors,

community members and most notably employees. Lipton's whole career

(and much of Wachtell Lipton's business model) has been organized

around these few ideas. His lifelong goal has been to safeguard

managers against hostile takeovers and, increasingly, activist

campaigns conducted in the name of shareholders.

Lucian Bebchuk, age 59, likes to attack blue chip stocks. His

astonishing success has made him the only law professor listed among

the 100 Most Influential People in Finance by Treasury and Risk

magazine. A lowly student clinic led by Bebchuk—the Shareholder's

Rights Project—has destaggered about 100 corporate boards on the

Fortune 500 and the S&P 500 stock index since 2011. As a critic of CEO

compensation, Bebchuk paved the way for the Dodd-Frank Act rules that

give shareholders more "say on pay." Shareholder activism has drawn

him into debates with Lipton in 2002, 2003, 2007, and more or less

continually since 2012.

In 2012, Lipton still referred to Bebchuk with senatorial decorum, as

"my friend," and teased him about reenacting the Hamilton-Burr duel.

But something soon changed. Perhaps Lipton was disturbed by the effort

to debunk his deepest belief about the long-term effects of activism.

Or perhaps what changed were the tides of fortune. For the only thing

that the two can agree on is that, in Lipton's words, the "activist

hedge funds are winning the war." And so the iconoclast is no longer

amusing to the icon.

With a revolving cast of big-name partners, Lipton has churned out

ever more frequent and vicious memos. He called Bebchuk's paper

"extreme and eccentric"; "tendentious and misleading"; and "not a work

of serious scholarship." He gleefully noted that a sitting SEC

commissioner called another paper by Bebchuk so "shoddy" as to

constitute securities fraud. (Thirty-four professors rallied in

Bebchuk's defense and jumped on the commissioner for abusing his

power.) Bebchuk and Lipton lobbed posts back and forth on the Harvard

corporate governance blog with "na-na-na-na-na" titles. "Don't Run

Away From the Evidence" led to "Still No Valid Evidence," which led to

"Still Running Away From the Evidence."

When Lipton was recently asked what he'd say to Bebchuk over a cup of

coffee, he could no longer contemplate the idea: "I am afraid that

professor Bebchuk is so invested in, and obsessed with, his mistaken

views as to business and the economy that any conversation about

governance and activism over a cup of coffee, or other venue, would be

a waste of time."

Lipton blames "short-termist" hedge funds for America's economic

stagnation and inequality since the financial crisis. He even touts a

study blaming them for the financial crisis. His memos on activism are

themselves obsessive, overgeneralized, and over-the-top. They also may

be right.

Age of the activist investor

it has become a common meme that we live in the "age of the activist

investor." Estimated assets under activist management in 2014 ranged

from $120 billion to more than $200 billion. On the low end, that's up

269 percent since 2009, or 4,344 percent since 2001, according to the

Alternative Investment Management Association, a trade group.

Activists attract funds because they win. Nearly three-quarters of

activist demands were at least partially satisfied in 2014, according

to the data collector Activist Insight. Ernst & Young says that half

of S&P 500 companies engaged with activists in 2013. But even that

understates their impact, because the way to pre-empt an attack is to

adopt their mindset. Boston Consulting Group advises companies to "be

your own activist."

Wachtell is rare among top law firms in categorically refusing to

advise activist hedge funds. It helped 20 companies to quell activism

in 2014, and Wachtell dealmakers spend an increasing amount of time

playing firefighter. Lipton put the portion of his time devoted to

manning the fire hose at 25 to 30 percent. Daniel Neff, one of the

co-chairmen of the firm, estimates that activism consumes about 20

percent of his own time; he had answered an alarm from a Fortune 200

CEO just before we spoke.

Lipton urges directors to go through a "fire drill" at least once a

year, practicing how they would respond to an activist demand.

Sometimes the fire drill takes the form of play acting. Who gets to

play billionaire activist investor Carl Icahn, they wouldn't say.

The Wachtell lawyers didn't see the comic potential because they take

activism so seriously, and so personally. When asked if the tone of

their memos was perhaps a touch Scalia-esque, Steven Rosenblum, the

mild-mannered corporate co-chairman, replies that activists are far

more shrill. "They are flat-out uncivil, rude, loud and obnoxious," he

says. "They are incredibly unpleasant and total bullies. People should

not conduct themselves that way." Sabastian Niles, a young counsel

whom Lipton jokingly calls the firm's activist defense department,

says that over the past three months, three separate activists had

said to three CEO clients of Wachtell: "I will destroy you" if they

didn't do XYZ.

Lipton rose to prominence in the 1980s defending against corporate

raiders like Icahn, when they needed to win an outright majority of

the board to gain corporate control. For Lipton, the only difference

between corporate raiding and modern activism is that the Icahns of

the world figured out how to get their way with only 2 percent of the

share register. To seize effective control of the board, activists

harness the voting power of the largest investors. Their secret is

that giant stock funds outsource their votes to proxy advisory firms,

which routinely side with activists. And thanks in no small part to

Bebchuk, there are few staggered boards left to retard shifts in

voting power.

The activist trend has snowballed in recent years for several reasons,

some observers say. First, share ownership has consolidated among a

handful of giant asset managers, so the top few shareholders can swing

control of the board. Second, the giant asset managers are rapidly

losing market share to low-fee Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs). That

makes the institutional investors desperate to show high immediate

returns. So instead of activists going hat in hand to the

institutions, the institutions now approach the activists with

"requests for activism." This practice is so common that there is even

a name for them in the industry: RFAs.

Competing perspectives

Whether all this is for good or evil, or both, depends on which

narrative you accept. According to the hedge fund narrative, activists

champion little-guy shareholders against fat-cat CEOs of lousy

companies, who feed at the corporate trough with their cronies. "Wachtell

has a great business defending corporate America and particularly

Lipton himself," says Marc Weingarten of Schulte Roth & Zabel, the

dominant firm for activists along with Olshan Frome Wolosky. "It gives

no credit to what activists are clearly doing, which is making

managers more focused on maximizing shareholder value than on

self-aggrandizement and lining their own pockets."

According to the corporate narrative, activists are billionaire

hedgies who are out to make a quick buck, while driving great

companies and the economy into a ditch. Studies find that activists

typically hold a stock for only nine months before bailing out. In

that short time, they will aim at all costs to hack employment, R&D

and capital expenditures; overload the company with debt; return money

to shareholders through dividends and buybacks; and, as the ultimate

goal, goose the stock through M&A activity. "At bottom, every activist

campaign is one or two steps to sell the company," says Wachtell's

Neff.

There's truth to both perspectives, as shown by the two 2014 activist

deals profiled elsewhere in this issue. Both involved takeovers—for

while Neff may overstate matters, Activist Insight confirms that 49

percent of last year's activist campaigns made public demands related

to M&A outcomes. In the CommonWealth

REIT deal, the Icahn protégé Keith Meister appears to have

created real value for shareholders by throwing out the father-and-son

directors to whom the CEO had given exclusive power to manage the

REIT's real estate, and who were botching the job.

In the case of

Allergan, the activist

standard-bearer William Ackman made a failed $53 billion run at the

admired maker of Botox. Allergan typically devoted 17 percent of sales

to R&D. It cut that back to 13 percent during the takeover battle, and

the white knight buyer cut it to 7 percent of combined sales. Ackman's

bidder historically held R&D at 3 percent.

"Ackman said this is the most accretive deal he'd ever seen," notes

Wachtell's Neff, who advised Allergan. "Why? Because they would slash

R&D. They took out the best performer in its sector. Allergan didn't

need fixing." For Neff, Allergan is a cautionary tale of killing

innovation. And while Botox isn't exactly a life-saving drug, it is

innovative. The author of "A Culture of Narcissism" might have noted

that America is now too superficial to invest deeply in cosmetic

surgery.

Despite Allergan, the hedge fund account of shareholder activism

prevails in the press and the legal academy. As Lawrence Fink, CEO of

the giant money manager Blackrock Inc., noted last year in an

interview critical of hedge funds: "The narrative today is so loud now

on the activist side."

Some are searching for a middle ground. Writing in the Harvard

Business Review, Harvard professor Guhan Subramanian laments a debate

characterized by "shrill voices, a seemingly unbridgeable divide

between shareholder activists and managers, rampant conflicts of

interest, and previously staked out positions that crowd out

thoughtful discussion."

The outspoken Chief Justice Leo Strine Jr. of the Delaware Supreme

Court ["Tell Us What You Really Feel, Leo," March 2012] relates a

story that lies somewhere in between the two poles. In Strine's

telling, the little-guy investor needs to be protected from the

self-dealing of both company managers and activist money managers.

"The media and academia are captive to intellectual laziness," Strine

says. "It's easier to write a story about the bad, bad managers

against the innocent shareholders, as if it's still 1935. It's much

harder to write about the current complexities of a system of monied

interests (money manager stockholders) versus other monied interests

(corporate managers), and how the poor incentives of that system often

give the shaft to ordinary Americans, both as investors who have to

invest through money manager intermediaries to save for retirement and

college for their kids, and as workers who need employment from

corporations to feed their families."

At 88, Ira Millstein of Weil, Gotshal & Manges is perhaps the only

corporate law guru to outrank Strine and Lipton. ("If I don't have a

long-term perspective at my age, when am I ever going to have one?" he

jokes.) "As far as Marty's concerned, I disagree because he's damning

the whole movement," says Millstein. "I know activist hedge funds that

are in the business of promoting long-term growth. I know other

activists who are only interested in jerking the stock a little bit. I

think there are plenty of both."

Fishing with dynamite

What Bebchuk does in "The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism" is

to see which narrative dominates if you ignore the anecdotes and study

the data. Working with University of Chicago-trained financial

economists Alon Brav and Wei Jiang, he tracked the performance of

every activist-targeted company over the long term. Not over two days,

but over five years. Bebchuk writes drily, "When available, economists

commonly prefer objective empirical evidence over unverifiable reports

of affected individuals."

The finding that made Lipton go ballistic is put simply by University

of Chicago professor Steven Kaplan: "When you get these activists

involved, the stock price goes up and stays up, and if anything, the

operating metrics improve. Done. End of story."

To its critics, Bebchuk's paper is far from the end of the story.

Scholars ranging from Columbia Law School's John Coffee Jr. to Yvan

Allaire of the Institute for Governance of Private and Public

Organizations find the data ambiguous and methodologically flawed.

Both attribute any gains by shareholders to a combination of fleeting

takeover premiums and wealth transfers from employees (as the result

of layoffs or wage cuts) or bondholders (as the result of downgrades

or bankruptcies). In other words, Ackman and some shareholders are

getting rich on the back of workers and pensioners.

"I don't agree with Bebchuk, because you can't prove a case with a

number," says Millstein. "I'm not saying he's twisting the numbers,

but he's coming up with the conclusions he believes in the first

place." Says Lynn Stout of Cornell Law School: "He's trying to prove

his own theories."

In Stout's view, Bebchuk is looking at the wrong thing. "He should be

looking at what activists do to the economy as a whole," she says. "If

Bebchuk went to a fishing village, he would find that people catch

more fish with dynamite than nets, and he would conclude that everyone

should fish with dynamite." That doesn't mean the dynamite is good for

the pond. For instance, Bebchuk's study says nothing about the fate of

the many activist targets that disappeared from the sample. By

Bebchuk's own numbers, activist intervention increased the chance of

corporate death over the study period from 42 to 49 percent. "To me,

that says we're dynamiting a lot of fish here," says Stout.

Bebchuk's supporters say it takes a model to beat a model. So why

doesn't Wachtell fund counterresearch? "If we wanted to phony up a

model, we could do the same thing he does," retorts Lipton. He thinks

the evidence, "empirical, experiential, and overwhelming," is already

on his side.

Roughly 95 percent of S&P 500 profits last year were funneled back to

shareholders through buybacks or dividends, according to a Bloomberg

projection. A study by J.W. Mason of the Roosevelt Institute found

that only 10 percent of profits plus borrowings were being reinvested

in public companies today—compared with 40 percent in the 1960s and

1970s. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Center for American Progress

cites a recent study showing investment by private companies to be

more than double today's rate for public ones. Chicago economists say

that shareholders are allocating all that capital efficiently. Others,

like Pavlos Masouros of Leiden University, think the shortfall in

investment is retarding GDP growth, and amplifying inequality.

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers is persuaded that hedge

fund activism is a macroeconomic problem. "We are having an epidemic

right now of activism directed at getting management to choke off

investment," he says. "It seems unlikely to me that there has been a

major increase in managerial abuse the last few years. It seems

unlikely to me that American business has been chronically

over-investing the last few decades. That makes me think there is

likely too much aggressive activism," sometimes at the expense of

employees.

'How do we fix things?'

Lipton speaks of the lifetime contract between a company and its

employees, and Neff says that philosophy carries over to law firm

management. Wachtell Lipton resisted pressure from some partners

during the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, and refused to lay off a

single summer associate or staffer. "We would not put a family's

breadwinner out on the street and change his and his family's life so

the partners can make a couple more dollars," says Neff. "That

attitude comes down from the white-haired gentleman."

Some critics find it a bit rich when Lipton echoes liberal think tanks

on distributional inequality. They note that Lipton never met an

executive pay plan he couldn't defend, including the $210 million that

The Home Depot Inc. awarded in 2006 to CEO Robert Nardelli despite its

flagging share price. Lipton's consistent loyalties lie not with

stakeholders, they suggest, but management.

"Has there ever been an issue where Marty Lipton sided with

shareholders against management?" asks Yale Law School's Jonathan

Macey. "I believe the answer to that question is no."

Macey goes further, and queries whether Lipton's loyalty to CEOs

should disqualify his law firm from acting for directors. "Suppose I'm

a director of a public company, and we are faced with activist

investors. Suppose the CEO says, let's hire Wachtell. If I really

thought that law firm took Marty Lipton's radical view"—and Macey

takes pains to say that although it is possible, he does not really

think the firm would do that—"then I think it would be a violation of

the fiduciary duty of loyalty to hire that firm. Because Marty Lipton

is not interested in protecting shareholders; he's interested in

protecting management."

Lipton replies that while his memos speak only for the lawyers who

sign them, they are absolutely consonant with fiduciary duties. All

Wachtell lawyers advise directors to consult with activists, Lipton

said, and sometimes advise them to change business strategy. "I've had

clients with mediocre management," added Neff, "and I said to the

activist: 'OK, you're right, how do we fix things?'"

So would Lipton concede that in a bad company, activists can be good

for the economy? "No!" he shoots back. "They'll push to fire more

people and cut more R&D and go too far. They'll want two times too

much. It's terribly macroeconomically harmful."

Though his memos chronicle every shot fired across the activists' bow,

Lipton knows he's still losing. The only recent development that truly

comforts him is the letter sent to CEOs a year ago by Blackrock's

Larry Fink. "It concerns us," Fink wrote, "that, in the wake of the

financial crisis, many companies have shied away from investing in the

future growth of their companies. Too many companies have cut capital

expenditure and increased debt to boost dividends and increase share

buybacks." As Fink later put it more succinctly, activists "destroy

jobs."

Fink's opinion matters more than most, because he speaks for $4

trillion in assets.

Lipton will never win his war until institutional shareholders vote

against activists more. He is the first to say so, and others agree.

Chief Justice Strine of Delaware urges institutional shareholders to

tailor their voting policies to their investors' investment

horizons—and to recognize the unique long-term outlook of people

relying on index funds for college or retirement.

That change in mentality could be promoted through systemic reform.

Summers says that policy changes to give long-term shareholders more

voting power or managers more tools to fend off activists deserve

serious consideration. But change could also be achieved through the

exercise of old-fashioned good judgment. "Companies and pension funds

are getting smarter," says Millstein. "If the real investors think the

activists are wrong, then they don't have to go along."

|

Copyright 2015. ALM Media Properties, LLC. |

|