Shareholder Activism:

Who, What, When, and How?

Posted by Mary Ann Cloyd,

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, on Tuesday, April 7, 2015

|

Editor’s Note: Mary Ann Cloyd is leader of the

Center for Board Governance at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. The

following post is based on a PricewaterhouseCoopers publication,

available

here. |

Who are today’s activists and what do they want?

Shareholder activism spectrum

“Activism” represents a

range of activities by one or more of a publicly traded corporation’s

shareholders that are intended to result in some change in the

corporation. The activities fall along a spectrum based on the

significance of the desired change and the assertiveness of the

investors’ activities. On the more aggressive end of the spectrum is

hedge fund activism that seeks a significant change to the company’s

strategy, financial structure, management, or board. On the other end

of the spectrum are one-on-one engagements between shareholders and

companies triggered by Dodd-Frank’s “say on pay” advisory vote.

The purpose of this

post is to provide an overview of activism along this spectrum: who

the activists are, what they want, when they are likely to approach a

company, the tactics most likely to be used, how different types of

activism along the spectrum cumulate, and ways that companies can both

prepare for and respond to each type of activism.

Hedge fund activism

At the most assertive

end of the spectrum is hedge fund activism, when an investor, usually

a hedge fund or other investor aligned with a hedge fund, seeks to

effect a significant change in the company’s strategy.

Background

Some of these activists

have been engaged in this type of activity for decades (e.g., Carl

Icahn, Nelson Peltz). In the 1980s, these activists frequently sought

the breakup of the company—hence their frequent characterization as

“corporate raiders.” These activists generally used their own money to

obtain a large block of the company’s shares and engage in a proxy

contest for control of the board.

In the 1990s, new funds

entered this market niche (e.g., Ralph Whitworth’s Relational

Investors, Robert Monks’ LENS Fund, John Paulson’s Paulson & Co., and

Andrew Shapiro’s Lawndale Capital). These new funds raised money from

other investors and used minority board representation (i.e., one or

two board seats, rather than a board majority) to influence corporate

strategy. While a company breakup was still one of the potential

changes sought by these activists, many also sought new executive

management, operational efficiencies, or financial restructuring.

Today

During the past decade,

the number of activist hedge funds across the globe has dramatically

increased, with total assets under management now exceeding $100

billion. Since 2003 (and through May 2014), 275 new activist hedge

funds were launched.

|

Forty-one

percent of today’s activist hedge funds focus their activities

on North America, and 32% have a focus that spans across global

regions. The others focus on specific regions: Asia (15%),

Europe (8%), and other regions of the world (4%). |

Why?

The goals of today’s

activist hedge funds are broad, including all of those historically

sought, as well as changes that fall within the category of “capital

allocation strategy” (e.g., return of large amounts of reserved cash

to investors through stock buybacks or dividends, revisions to the

company’s acquisition strategy).

How?

The tactics of these

newest activists are also evolving. Many are spending time talking to

the company in an effort to negotiate consensus around specific

changes intended to unlock value, before pursuing a proxy contest or

other more “public” (e.g., media campaign) activities. They may also

spend pre-announcement time talking to some of the company’s other

shareholders to gauge receptivity to their contemplated changes.

Lastly, these activists (along with the companies responding to them)

are grappling with the potential impact of high-frequency traders on

the identity of the shareholder base that is eligible to vote on proxy

matters.

|

Some contend

that hedge fund activism improves a company’s stock price (at

least in the short term), operational performance, and other

measures of share value (including more disciplined capital

investments). Others contend that, over the long term, hedge

fund activism increases the company’s share price volatility as

well as its leverage, without measurable improvements around

cash management or R&D spending. |

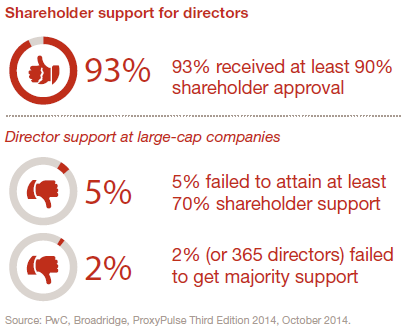

“Vote no” campaign

Moving down the

activism spectrum are “vote no” campaigns where an investor (or

coalition of investors) urges shareholders to withhold their votes

from one or more of the board-nominated director candidates.

Why?

These campaigns are

rarely successful in forcing an involuntary ouster of a director,

because at most companies this would require support from a majority

of outstanding shares—not just a majority of the votes cast at the

meeting, which is a much lower threshold. But, particularly when the

challenged director is not the company’s CEO/chair, a “vote no”

campaign can influence the candidate to voluntarily withdraw from the

election. If the level of “negative” vote was relatively significant,

a director may be replaced during his/her subsequent term.

Who?

These campaigns are

usually sponsored by public or labor pension funds.

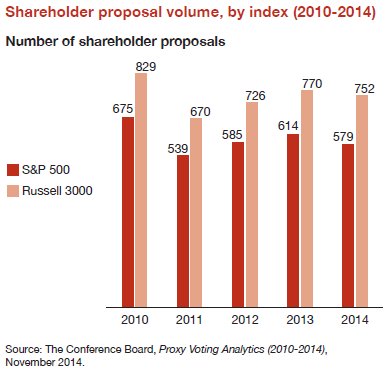

Shareholder proposal

Further down the

spectrum is sponsorship of a shareholder proposal (or, more often, the

threat of a shareholder proposal).

Why?

The goal of these

investors is usually to encourage one of four types of change.

-

A change to the

board’s governance policies or practices (e.g., declassify the

board, adopt majority voting, limit the company’s ability to shift

legal fees to unsuccessful shareholder litigants, remove exclusive

forum bylaw provisions, provide transparency around succession

planning, provide proxy access), or a change to the board

composition (e.g., increase board diversity, name an independent

director as chair);

-

A change to the

company’s executive compensation plans (e.g., a change in vesting

terms);

-

A change to the

company’s oversight of certain functions (e.g., audit, risk

management); or

-

A change to the

company’s behavior as a corporate citizen (e.g., political spending

or lobbying, environmental practices, climate change or resource

scarcity preparedness, labor practices)

|

Recently, some investors have also used shareholder proposals

to address more fundamental changes to corporate strategy

(e.g., break up the company, sell certain assets, return

capital to shareholders, or retain an advisor to evaluate

alternative ways to increase shareholder value). These

proposals are usually related to a more assertive activism

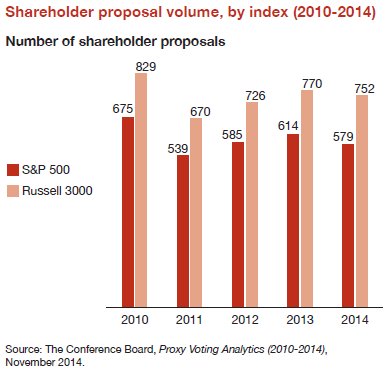

campaign, as discussed under “Hedge Fund Activism.”Source:

PwC analysis, The Conference Board, Proxy Voting Analytics

(2010-2014), November 2014. |

Who?

Shareholder proposals

are sponsored by a wide range of different types of investors:

-

Governance, executive

compensation and risk/audit oversight proposals are usually

sponsored by public pension funds, labor pension funds, or

individual investors. These investors believe that these changes may

promote more effective corporate governance (including more reliable

financial reporting), and that good governance enhances shareholder

value.

-

Environmental and

social proposals are usually sponsored by labor pension funds, ESG-oriented

investment managers, religious groups, or coalitions of like-minded

investors. These investors believe that these changes may provide

broader societal value which also—over the long-term—benefits the

corporation and all of its stakeholders.

-

“Shareholder value”

proposals are usually sponsored by hedge funds as a component of a

more assertive activist campaign.

Say on pay

On the more passive end

of the spectrum are investor activities triggered by a company’s “say

on pay” advisory vote proxy item. These activities are usually limited

to letters to a company (typically directed to the compensation

committee of the board) or meetings/phone calls with the company

(typically involving the company’s general counsel, corporate

secretary, and/or compensation committee chair).

Why?

The goal of these

conversations is, generally, either to effect a substantive change to

the compensation plan, or to alter how it is described in shareholder

communications.

Who?

A wide range of

investors participate in this type of “activism,” including

traditional asset managers, mutual funds, pension funds, and

individuals. Since “say on pay” is a proxy item presented to all

shareholders for an advisory vote, all shareholders who vote generally

must form a view about the company’s executive compensation plans. A

subset of these voting shareholders may decide to convey these views

to the company; doing so generally does not require a significant

amount of resources. These investors are particularly likely to do so

if they believe the plan does not align pay with performance, contains

objectionable features (e.g., certain vesting terms), or utilizes

inappropriate performance metrics.

When

is a company likely to be the target of activism?

Although each hedge

fund activist’s process for identifying targets is proprietary,

most share certain broad similarities:

-

The company has a low

market value relative to book value, but is profitable, generally

has a well-regarded brand, and has sound operating cash flows and

return on assets. Alternatively, the company’s cash reserves exceed

both its own historic norms and those of its peers. This is a risk

particularly when the market is unclear about the company’s

rationale for the large reserve. For multi- business companies,

activists are also alert for one or more of the company’s business

lines or sectors that are significantly underperforming in its

market.

-

Institutional

investors own the vast majority of the company’s outstanding voting

stock.

-

The company’s board

composition does not meet all of today’s “best practice”

expectations. For example, activists know that other investors may

be more likely to support their efforts when the board is perceived

as being “stale”—that is, the board has had few new directors over

the past three to five years, and most of the existing directors

have served for very long periods. Companies that have been

repeatedly targeted by non-hedge fund activists are also attractive

to some hedge funds who are alert to the cumulative impact of

shareholder dissatisfaction.

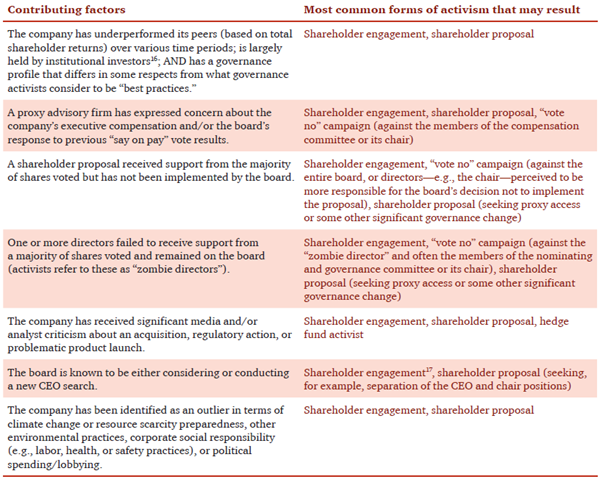

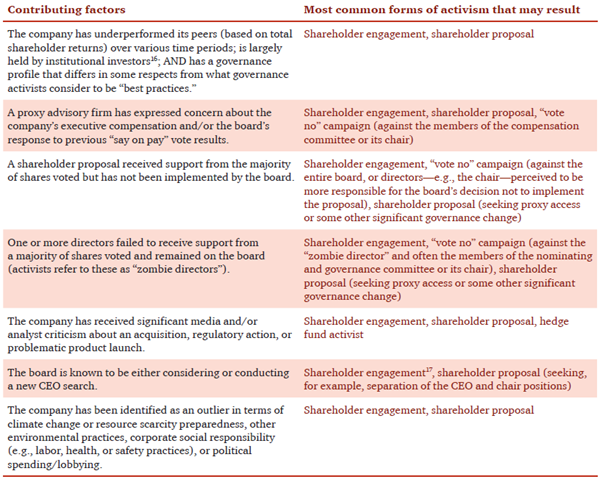

A company is most

likely to be a target of non-hedge fund activism based on a

combination of the following factors:

How can a company effectively

prepare for—and respond to—an activist campaign?

Prepare

We believe that

companies that put themselves in the shoes of an activist will be most

able to anticipate, prepare for, and respond to an activist campaign.

In our view, there are four key steps that a company and its board

should consider before an activist knocks on the door:

Critically

evaluate all business lines and market regions. Some

activists have reported that when they succeed in getting on a

target’s board, one of the first things they notice is that the

information the board has been receiving from management is often

extremely voluminous and granular, and does not aggregate data in a

way that highlights underperforming assets.

-

Companies (and

boards) may want to reassess how the data they review is aggregated

and presented. Are revenues and costs of each line of business

(including R&D costs) and each market region clearly depicted, so

that the P&L of each component of the business strategy can be

critically assessed? This assessment should be undertaken in

consideration of the possible impact on the company’s segment

reporting, and in consultation with the company’s management and

likely its independent auditor.

Monitor the

company’s ownership and understand the activists.

Companies routinely monitor their ownership base for significant

shifts, but they may also want to ensure that they know whether

activists (of any type) are current shareholders.

Evaluate

the “risk factors.” Knowing in advance how an activist

might criticize a company allows a company and its board to consider

whether to proactively address one or more of the risk factors, which

in turn can strengthen its credibility with the company’s overall

shareholder base. If multiple risk factors exist, the company can also

reduce its risk by addressing just one or two of the higher risk

factors.

Develop an

engagement plan that is tailored to the company’s shareholders and the

issues that the company faces. If a company identifies

areas that may attract the attention of an activist, developing a plan

to engage with its other shareholders around these topics can help

prepare for—and in some cases may help to avoid—an activist campaign.

This is true even if the company decides not to make any changes.

-

Activists typically

expect to engage with both members of management and the board.

Accordingly, the engagement plan should prepare for either

circumstance.

-

Whether the company

decides to make changes or not, explaining to the company’s most

significant shareholders why decisions have been made will help

these shareholders better understand how directors are fulfilling

their oversight responsibilities, strengthening their confidence

that directors are acting in investors’ best long-term interests.

-

These communications

are often most effective when the company has a history of ongoing

engagement with its shareholders. Sometimes, depending on the

company’s shareholder profile, the company may opt to defer actual

execution of this plan until some future event occurs (e.g., an

activist in fact approaches the company, or files a Schedule 13d

with the SEC, which effectively announces its intent to seek one or

more board seats). Preparing the plan, however, enables the company

to act quickly when circumstances warrant.

Respond

In responding to an

activist’s approach, consider the advice that large institutional

investors have shared with us: good ideas can come from anyone. While

there may be circumstances that call for more defensive responses to

an activist’s campaign (e.g., litigation), in general, we believe the

most effective response plans have three components:

Objectively

consider the activist’s ideas. By the time an activist

first approaches a company, the activist has usually already (a)

developed specific proposals for unlocking value at the company, at

least in the short term, and (b) discussed (and sometimes consequently

revised) these ideas with a select few of the company’s shareholders.

Even if these conversations have not occurred by the time the activist

first approaches the company, they are likely to occur soon

thereafter. The company’s institutional investors generally spend

considerable time objectively evaluating the activist’s suggestion—and

most investors expect that the company’s executive management and

board will be similarly open- minded and deliberate.

Look for

areas around which to build consensus. In 2013, 72 of

the 90 US board seats won by activists were based on voluntary

agreements with the company, rather than via a shareholder vote. This

demonstrates that most targeted companies are finding ways to work

with activists, avoiding the potentially high costs of proxy contests.

Activists are also motivated to reach agreement if possible. If given

the option, most activists would prefer to spend as little time as

possible to achieve the changes they believe will enhance the value of

their investment in the company. While they may continue to own

company shares for extensive periods of time, being able to move their

attention and energy to their next target helps to boost the returns

to their own investors.

Actively

engage with the company’s key shareholders to tell the company’s

story. An activist will likely be engaging with fellow

investors, so it’s important that key shareholders also hear from the

company’s management and often the board. In the best case, the

company already has established a level of credibility with those

shareholders upon which new communications can build. If the company

does not believe the activist’s proposed changes are in the best

long-term interests of the company and its owners, investors will want

to know why—and just as importantly, the process the company used to

reach this conclusion. If the activist and company are able to reach

an agreement, investors will want to hear that the executives and

directors embrace the changes as good for the company. Company leaders

that are able to demonstrate to investors that they were part of

positive changes, rather than simply had changes thrust upon them,

enhance investor confidence in their stewardship.

Epilogue—life after activism

When the activism has

concluded—the annual meeting is over, changes have been implemented,

or the hedge fund has moved its attention to another target—the risk

of additional activism doesn’t go away. Depending on how the company

has responded to the activism, the significance of any changes, and

the perception of the board’s independence and open-mindedness, the

company may again be targeted. Incorporating the “Prepare” analysis

into the company’s ongoing processes, conducting periodic

self-assessments for risk factors, and engaging in a tailored and

focused shareholder engagement program can enhance the company’s

resiliency, strengthening its long-term relationship with investors.

|

Harvard Law School Forum

on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation

All copyright and trademarks in content on this site are owned by

their respective owners. Other content © 2015 The President and

Fellows of Harvard College. |

|