Technology

How Amazon’s Long

Game Yielded a Retail Juggernaut

Parcel delivery in Battery

Park City in New York. One analyst predicts that in five years, 50 percent

of American households will have joined Amazon Prime.

Credit Ángel Franco/The New

York Times |

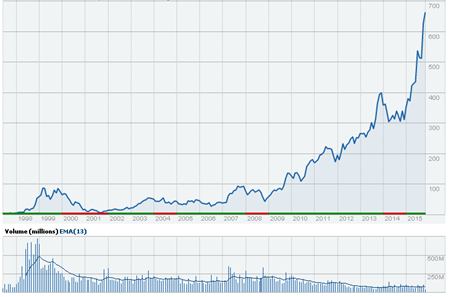

To study

the graph of Amazon’s stock performance in 2015

is to witness a series of stepwise lurches toward commanding new heights. Over

all, the stock market has been flat this year, and technology companies, as a

group,

haven’t fared much better.

Then there’s

Amazon, which slipped the atmosphere.

Shares of

Jeff Bezos’s company have doubled in value

so far in 2015, pushing

Amazon into the world’s 10 largest

companies by stock market value, where it jockeys for position with General

Electric and is far ahead of Walmart.

There is a

simple explanation for Amazon’s rise, and also a second, more complicated one.

The simple story involves Amazon Web Services, the company’s cloud-computing

business, which rents out vast amounts of server space to other companies.

Amazon began disclosing A.W.S.’s financial performance in April, and the numbers

showed that selling server space was a much bigger business than anyone had

realized.

Deutsche Bank estimates that A.W.S., which

is less than a decade old, could soon be worth $160 billion as a stand-alone

company. That’s more valuable than Intel.

Yet the

disclosure of A.W.S.’s size has obscured a deeper change at Amazon. For years,

observers have wondered if Amazon’s

shopping business — you know, its main business — could ever really work.

Investors gave Mr. Bezos enormous leeway to spend billions building out a

distribution-center infrastructure, but it remained a semi-open question if the

scale and pace of investments would ever pay off. Could this company ever make a

whole lot of money selling so much for so little?

As we embark

upon another holiday shopping season, the answer is becoming clear: Yes, Amazon

can make money selling stuff. In the

flood of rapturous reviews from stock

analysts over

the company’s earnings report last month,

several noted that Amazon’s retail operations had reached a “critical scale” or

an “inflection point.” They meant that Amazon’s enormous investments in

infrastructure and logistics have begun to pay off. The company keeps capturing

a larger slice of American and even international purchases. It keeps attracting

more users to its Prime fast-shipping subscription program, and, albeit slowly,

it is beginning to scratch out higher profits from shoppers.

The Rapid Rise in Amazon Shares

Now that Amazon

has hit this point, it’s difficult to see how any other retailer could catch up

anytime soon. I recently asked a couple of Silicon Valley venture capitalists

who have previously made huge investments in e-commerce whether they were keen

to spend any more in the sector. They weren’t, citing Amazon.

This week I also

asked several stock analysts if they could see any potential competitive threat

to Amazon’s online sales dominance. Some literally laughed at the question.

“The truth is

they’re building a really insurmountable infrastructure that I don’t see how

others can really deal with,” said Ben Schachter, who studies Amazon for

Macquarie Securities.

It may be no exaggeration to say that at least in North America and

Europe, e-commerce as an expansive category of Internet exploration is

on the wane. Mr. Bezos has already won the game.

There are many

who will lament that Amazon has reached these heights, and not just its retail

competitors. As with Walmart before it, Amazon’s rise engenders fears of

economic and cultural totalitarianism —

which are reasonable concerns, even if

often overblown. Many critics are worried,

too,

about how the company treats its workers

(Amazon has

argued that they’re treated well) and

how it affects local and national economic activity

(a matter of constant dispute), among many other issues.

And while we’re

in the to-be-sure part of this column, let’s note that Amazon also faces a wider

set of competitive threats internationally. Although it has reported

increasingly brisk sales in India, the company has had a difficult time breaking

into the lucrative Chinese market, where Alibaba dominates the shopping scene.

Indeed,

Alibaba’s sales and profits dwarf Amazon’s. On Singles Day, held in China on

Nov. 11 to celebrate the proudly unmarried, as best as I can tell,

Alibaba rang in more than $14 billion in

sales, which is more than Americans will spend both offline and online over the

entire post-Thanksgiving weekend. (Because Alibaba’s ecommerce businesses tend

to connect buyers and sellers, its sales aren’t booked directly as revenue;

instead, it takes a cut of each purchase made on its platform.)

Even

domestically, competitors aren’t sitting idle. Over the last year, investors

have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into Jet.com,

which aims to become a discount competitor to Amazon.

The firm’s odds of success, though, have always looked long, and seem to

keep getting longer.

|

Credit

Stuart Goldenberg

|

|

Walmart, which

on Tuesday published earnings that

came in slightly above analysts’ expectations,

is also

spending billions to slow Amazon’s roll.

But Walmart said that in its latest quarter, e-commerce sales had grown only 10

percent from a year ago. Amazon’s retail sales rose 20 percent during the same

period.

Why is Amazon so

far ahead? It is difficult to resist marveling at the way Mr. Bezos has built

his indomitable shopping machine, and the very real advantages in price and

convenience that he has brought to America’s national pastime of buying stuff.

What has been key to this rise, and missing from many of his competitors’

efforts, is patience. In a very old-fashioned manner, one that is far out of

step with a corporate world in which milestones are measured every three months,

Amazon has been willing to build its empire methodically and at great cost over

almost two decades, despite skepticism from many sectors of the business world.

Now those

investments are beginning to bear fruit. It’s happening in fulfillment, which is

the business term for filling and shipping orders. Amazon has built more than

100 warehouses from which to package and ship goods, and it hasn’t really slowed

its pace in establishing more. Because the warehouses speed up Amazon’s

shipping, encouraging more shopping, the costs of these centers is becoming an

ever-smaller fraction of Amazon’s operations.

Amazon’s

investments in Prime, the $99-a-year service that offers free two-day shipping,

are also paying off. Last year

Mr. Bezos told me that people were

increasingly signing up for Prime for the company’s media offerings — the free

TV shows, music and movies that come with the subscription, and which Amazon has

been spending vast sums to produce.

Mr. Schachter,

of Macquarie Securities, estimates that there will be at least 40 million Prime

subscribers by the end of this year, and perhaps as many as 60 million, up from

an estimated 30 million at the beginning of 2015. He argued that Amazon’s

investments in giveaways will help make Prime more attractive to people in

lower-income groups. As a result, he predicted that by 2020, 50 percent of

American households will have joined Prime, “and that’s very conservative,” he

said.

Growth in Prime

subscriptions matters because Prime alters the psychology of shopping. Once

you’ve prepaid for shipping, you tend to start more of your shopping excursions

at Amazon. According to some estimates, people spend three or four times as much

with Amazon after they sign up to Prime.

Because Amazon

is still expanding madly, its expenses remain enormous and its retail profits

tiny. In its last quarter, its operating margin on the North American retail

business was 3.5 percent, while Amazon Web Services’s margin was 25 percent.

But this “Prime

effect” is key to Amazon’s long-term profitability. Analysts at Morgan Stanley

reported recently that “retail gross profit dollars per customer” — a fancy way

of measuring how much Amazon makes from each shopper — has accelerated in each

of the last four quarters, in part because of Prime. Amazon keeps winning “a

larger share of customers’ wallets,” the firm said, eventually “leading to a

period of sustained, rising profitability.”

Of course, many

other retailers could build services like Prime; in fact, many are. But it could

take them years to catch up.

“The thing about

retail is, the consumer has near-perfect information,” said Paul Vogel, an

analyst at Barclays. “So what’s the differentiator at this point? It’s

selection. It’s service. It’s convenience. It’s how easy it is to use their

interface. And Amazon’s got all this stuff already. How do you compete with

that? I don’t know, man. It’s really hard.”

Email:

farhad.manjoo@nytimes.com

A version of this article appears in print on November 19, 2015, on

page B1 of the New York edition with the headline: Long Game at Amazon

Produces Juggernaut.

© 2015 The

New York Times Company