|

THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

Tech

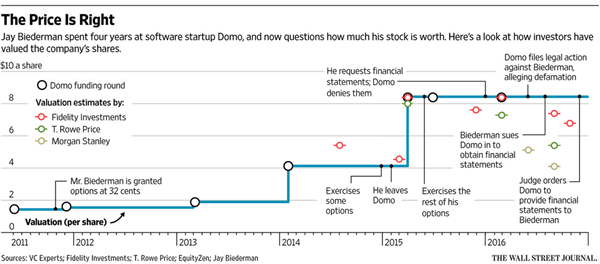

Former Employee Wins Legal Feud to Open Up Startup’s Books

Delaware ruling against Domo highlights shareholders’ rights as

companies stay private longer

|

Inside Domo’s office in American Fork, Utah. The startup shared

its audited financial statements with a former employee, after a

lawsuit.

PHOTO: JEFFREY D. ALLRED/THE DESERET NEWS/ASSOCIATED PRESS |

By

Rolfe Winkler

Jan. 26, 2017 8:00 a.m. ET

A former manager at

privately held Domo Inc. has prevailed in a legal fight to obtain

financial records from the company, affirming the rights of startup

investors and employee shareholders.

Last week, Jay Biederman

received Domo’s audited financial statements, according to people

familiar with the case, after a Delaware judge ruled last month that

he was entitled to the information so he can value his shares in the

business software company.

The ruling came nearly

seven months

after The Wall Street Journal chronicled

Mr. Biederman’s attempt to obtain the documents from Domo. Mr.

Biederman had sought the financial records for more than a year

before suing the company in

August in Delaware, where Domo is incorporated.

Mr. Biederman declined to

comment through an attorney.

Mr. Biederman’s victory

shines a spotlight on shareholders’ rights to inspect their company’s

books, an especially important privilege in an era when startups are

staying private longer and, as a result, avoiding mandatory public

disclosures.

Unlike publicly traded

companies, startups like Domo aren’t required by law to file financial

reports. Instead, mostly for competitive reasons, they typically keep

their revenue, profit and financial projections hidden from everyone

except their top investors.

Tech-startup valuations

also don’t fluctuate daily like the shares of publicly traded

companies. Venture investors typically set the valuations when

startups raise new financing every year or two. So it is difficult to

gauge how much these shares are worth without knowing a company’s

financial health.

It has been nearly a year

since

Domo was valued at $2 billion,

which would have made Mr. Biederman’s shares worth about $541,000. But

some mutual funds that hold the shares have marked them down as much

as 50% from that value, according to

The Wall Street Journal’s Startup Stock

Tracker, raising questions about the company’s current

value.

Mr. Biederman invoked

section 220 of Delaware’s corporate law to compel Domo to provide the

data, one of

a handful of rules that require

private companies to disclose their records to shareholders. The law

gives shareholders the right to inspect a company’s books, including a

list of stockholders, financial statements, articles of incorporation

and more, so long as they provide a “proper purpose” for their

request.

The judge in the Delaware

case, Sam Glasscock III, cited precedent in ruling in December that

Mr. Biederman’s purpose to value his shares was proper and directing

the company to provide audited financials.

At the time, the judge

said that the way Mr. Biederman “was treated at the beginning of his

request for documents was both unfortunate, and certainly…tested the

limits of good faith if not exceeded them.”

Part of the Delaware

dispute also was over provisions of the nondisclosure agreement that

Domo asked Mr. Biederman to sign in exchange for the financial

records, and additional documents related to his other allegations

against the company. The NDA was renegotiated and the judge asked Domo

to provide limited documentation related to the other allegations.

But the time Mr. Biederman

has spent waging his fight shows how difficult it can be for

shareholders to exercise such rights.

In January 2015, Mr.

Biederman, who was a strategic solutions manager at Domo according to

his LinkedIn profile, requested financial statements from the company,

and was fired a few days later, according to his complaint.

A year later, he asked for

the documents again, and Domo’s vice president of investor relations

responded in an email that “shareholders are not entitled to financial

information as a matter of law” since Domo is a privately held

company. Delaware

law states the opposite.

Two months later, in April

2016, Domo General Counsel Dan Stevenson sent him an email raising

questions about his request and threatening to sue him for breaching

his separation agreement.

Domo sued him in June, a

week after the first Journal story ran, filing two legal actions in

Utah where the company is based. One legal action was a demand for

arbitration alleging disparagement, the other a civil lawsuit in state

court alleging defamation and breach of contract.

The defamation case

pointed to allegedly “disparaging posts about Domo” that Mr. Biederman

put on his

Facebook page before the Journal

story ran. Domo claimed the posts—which included one that Domo says

suggested sexual harassment and drug abuse took place at the

company—harmed its business.

Mr. Biederman in September

won a motion in Utah state court to force Domo to arbitrate the

defamation claim, reducing his legal costs by consolidating the two

legal actions. The defamation claim was later dismissed after Domo

declined to arbitrate it, according to court transcripts. A separate

disparagement claim remains before the arbitrator.

To date, Mr. Biederman’s

Utah legal costs have totaled nearly $100,000, according to one of his

attorneys.

Write to

Rolfe Winkler

at

rolfe.winkler@wsj.com

|