THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

Markets

|

YOUR MONEY

|

WEEKEND INVESTOR

Bogle Sounds a Warning on Index Funds

The

father of the index fund says it’s probably only a matter of time

before they own half of all U.S. stocks; ‘I do not believe that

such concentration would serve the national interest’

|

Jack Bogle after speaking at

the 2018 Bogleheads Conference. The creator of the index fund

says their increasing dominance may create some of the ‘major

issues of the coming era.’ PHOTO: RYAN COLLERD FOR THE WALL

STREET JOURNAL |

By John C. Bogle

Nov. 29, 2018 10:15 a.m. ET

There no longer can be any doubt that the creation of

the first index mutual fund was the most successful

innovation—especially for investors—in modern financial history. The

question we need to ask ourselves now is: What happens if it becomes

too successful for its own good?

The First Index Investment Trust, which tracks the returns of the

S&P 500 and is now known as the Vanguard 500 Index Fund, was founded on December

31, 1975. It was the first “product,” as it were, of a new mutual fund manager,

The Vanguard Group, the company I had founded only one year earlier.

The fund’s August 1976 initial public offering may have been the

worst underwriting in Wall Street history. Despite the leadership of

the Street’s four largest retail brokers, the IPO fell far short of its original

$250 million target. The initial assets of 500 Index Fund totaled but $11.3

million—falling a mere 95% short of its goal.

The fund’s struggle for the attention (and dollars) of investors

was epic. Known as “Bogle’s

folly,” the fund’s novel strategy of simply tracking a broad market

index was almost totally rejected by Wall Street. The head of Fidelity, then by

far the fund industry’s largest firm, put the kiss of death on his tiny rival:

“I can’t believe that the great mass of investors are [sic] going to be

satisfied with just receiving average returns. The name of the game is to be the

best.”

Almost a decade passed before a second S&P 500 index fund was

formed, by Wells

Fargo in 1984. During that period, Vanguard’s index fund attracted

cash inflow averaging only $16 million per year.

Now let’s advance the clock to 2018. What a difference 42 years

makes! Equity index fund assets now total some $4.6 trillion, while total index

fund assets have surpassed $6 trillion. Of this total, about 70% is invested in

broad market index funds modeled on the original Vanguard fund.

Yes, U.S. index mutual funds have grown to huge size, with their

holdings doubling from 4.5% of total U.S. stock-market value in 2002 to 9% in

2009, and then almost doubling again to more than 17% in 2018. Even that

penetration understates the role of mutual fund managers, as they also offer

actively managed funds, and their combined assets amount to more than 35% of the

shares of U.S. corporations.

If historical trends continue, a handful of giant institutional

investors will one day hold voting control of virtually every large U.S.

corporation. Public policy cannot ignore this growing dominance, and consider

its impact on the financial markets, corporate governance, and regulation. These

will be major issues in the coming era.

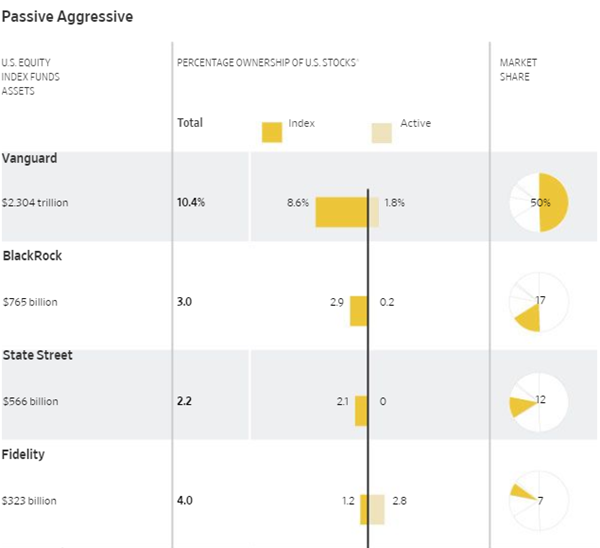

Three index fund managers dominate the field with a collective

81% share of index fund assets: Vanguard has a 51% share; BlackRock, 21%; and

State Street Global, 9%. Such domination exists primarily because the indexing

field attracts few new major entrants.

Why? Partly because of two high barriers to entry: the huge scale

enjoyed by the big indexers would be difficult to replicate by new entrants; and

index fund prices (their expense ratios, or fees) have been driven to

commodity-like levels, even to zero. If Fidelity’s 2018

offering of two zero-cost index funds has established a new “price

point” for index funds, the enthusiasm of additional firms to create new index

funds will diminish even further. So we can’t rely on new competitors to reduce

today’s concentration.

Most observers expect that the share of corporate ownership by

index funds will continue to grow over the next decade. It seems only a matter

of time until index mutual funds cross the 50% mark. If that were to happen, the

“Big Three” might own 30% or more of the U.S. stock market—effective control. I

do not believe that such concentration would serve the national interest.

My concerns are shared by many academic observers. In a draft

paper released in September, Prof. John C. Coates of Harvard Law School wrote

that indexing is reshaping corporate governance, and warned that we are tipping

toward a point where the voting power will be “controlled by a small number of

individuals” who can exercise “practical power over the majority of U.S. public

companies.” Professor Coates does not like what he sees, and offers tentative

policy options—some necessary, often painful to contemplate. His conclusion—“The

issue is not likely to go away”—is unarguable.

Solutions to resolve the issues connected with the concentration

of corporate ownership are not self-evident, but a number of tentative

possibilities have already been advanced:

• More competition from new entrants to the index field. For the

reasons noted above, this eventuality seems highly unlikely.

• Force giant index funds to spin off their assets into a number

of separate entities, each independently managed. Such a drastic step would—and

should—face near-insurmountable obstacles, for it would create havoc for index

investors and managers alike.

• Require index funds to hold just one company in any industry.

Leaving aside the dubious ability of either academia or federal bureaucrats to

define precisely what constitutes a given industry, such a drastic change would

lead to the destruction of today’s S&P 500 index fund, by common agreement, the

most beneficial innovation for investors of the modern age.

• Timely and full public disclosure by index funds of their

voting policies and public documentation of each engagement with corporate

managers. This would take today’s transparent and constructive governance

practices several steps further.

• Require index funds to retain an independent supervisory board

with full responsibility for all decisions regarding corporate governance. The

problem with this idea is that it is not clear how such a board could add to the

present scrutiny of the fund’s independent directors.

• Limit the voting power of corporate shares held by index

managers. But such a step would, in substance, transfer voting rights from

corporate stock owners, who care about the long-term, to corporate stock

renters, who do not... an absurd outcome.

• Enact federal legislation making it clear that directors of

index funds and other large money managers have a fiduciary duty to vote solely

in the interest of the funds’ shareholders. While I believe that such a

fiduciary duty is implicit today, making it explicit, with appropriate penalties

for violations, would be a constructive step.

It is time for public officials to consider the pros and cons of

these issues with indexers, the financial community, academia, and active

managers alike—and develop national policies that support high standards of

corporate governance. It will require their working together constructively and

cooperatively.

But one thing seems crystal clear. Even if present trends

continue (sometimes they don’t), the enormous value of index funds should not be

ignored. First, index funds provide investors with the most effective

stock-market strategy of all time: buy American business and hold it forever,

and do so at rock-bottom cost. Second, index funds are among the few truly

long-term owners of stocks—for all practical purposes, permanent owners of

capital—an enormously valuable asset to society. The long-term focus of index

funds is a much needed counterweight to the short-termism favored by so many

market participants.

Prof. Coates agrees that nothing should jeopardize the existence

of today’s index funds.

“Indexing has created real and large social benefits in the form

of lower expenses and greater long-term returns for millions of individuals

investing directly or indirectly for retirement,” he writes. “A ban on indexing

would clearly not be a good idea.” I can only say, “Amen” to those words.

Mr.

Bogle is founder of The Vanguard Group and creator of the first index mutual

fund. This article is adapted from his new book, “Stay the Course: The Story of

Vanguard and the Index Revolution,” to be published by Wiley on Dec. 6.