THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

|

How Etsy

Became America’s Unlikeliest Breadbasket

Homebound

consumers are flocking to the site for scones, biscuits,

breads, muffins, doughnuts and...alkaline tahini spelt

cookies. Homebound chefs are eager to satisfy this newfound

hunger for baked goods.

|

|

|

|

Suzanne McMinn

bakes cookies, scones, biscuits, muffins and breads in her

home kitchen, and mails them to all corners of the U.S. ANDREW

SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL |

Just about every morning since

America went on coronavirus lockdown, Suzanne McMinn has risen at 2 a.m. to bake

in her home kitchen. She’s working there up to 15 hours a day, seven days a

week.

But she’s not cooking for herself,

mostly. She’s cranking out dozens of orders daily for people all over the

U.S.—people who found her on Etsy.

Yes,

she sells bread on the site best known for knitted

hats and topical

greeting cards and, lately, hand-sewn

masks.

|

|

|

Ms. McMinn made scones and biscuits in her

kitchen on Wednesday. Lately she’s been baking up to 15 hours a day, seven

days a week. PHOTOS: ANDREW

SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL(2) |

On her farm in Roane County, W.Va.,

Ms. McMinn has cows, a dozen chickens and a kitchen in which she bakes cookies,

scones, biscuits, muffins and breads. She works alone but is hardly singular.

Thousands of her peers all across the country do what she does, every day: sell

the products of their humble home kitchens on the internet.

For most of America’s history,

people’s food came from no more than a few miles away, the distance a farmer

could travel in a horse-drawn wagon. During the Great Depression, rural farms

were an important source of food security for the country, a way for people to

feed themselves despite their poverty.

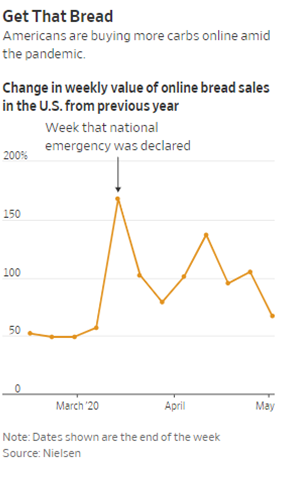

In these uncertain times, Americans

are once again taking solace in food. But the horse-drawn wagons have been

replaced by FedEx jets

and trucks, and the “penny restaurants” of yore have been replaced by

internet-savvy entrepreneurs who have discovered they can still eke out a

living, even while stuck at home.

Etsy is no longer the

company it once was. It was born in Brooklyn in 2005 as a market for individual

craftspeople and artisans to sell unique handmade gifts, including jewelry,

screen-printed T-shirts and

literally anything you can fashion out of distressed wood. Having gone

public in 2015, it’s fast becoming, as Chief Executive Josh Silverman said in

the company’s most recent earnings call, a place for “everyday essentials that

you need.”

Mr. Silverman, previously

at

eBay, was installed in 2017 by a board under pressure from activist

investors. Many of the changes he has instituted have been controversial with

both the company’s employees and its millions of sellers. They include cutting

costs through layoffs, mandatory off-site advertising of individual sellers’

goods, which can cut into their margins, and a general realignment of the

company’s mission: fewer crunchy-granola values, more shareholder value.

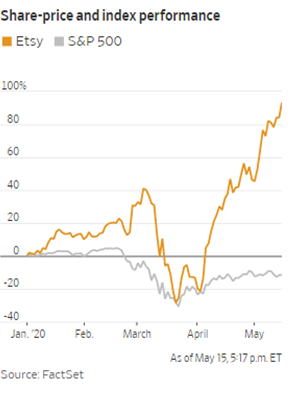

Nevertheless, the changes

seem to be working. Revenue in the latest quarter was double the level three

years earlier, right before Mr. Silverman took over, and Etsy has gone from

steady red ink to consistent profits. Its share price is up about 90% so far

this year.

In Etsy’s earnings call

this month, Mr. Silverman said business continued to surge in April, driven by

the sale of fabric face masks—Etsy sold about $133 million of them in the month,

the result of mass seller mobilization—and of the sorts of items homebound

shoppers want for their nests or to send to loved ones.

“We are seeing very strong growth in

brand-new buyers, and we’re excited by that,” he added.

In 2017 when Mr. Silverman took

over, the company’s revenue was growing, but its expenses were growing faster,

and its board had become convinced that its then-CEO, Chad Dickerson, had to go.

Mr. Silverman soon ended Etsy’s Values-Aligned Business team, responsible for

its environmental and social initiatives. The company also ceased being a

certified B Corp, a designation given to companies that are “using business as

a force

for good.” Mr. Silverman initiated a number of experiments at the

company, many of which he later admitted didn’t work, including an attempt to

get sellers to offer “free” shipping by rolling its cost into the price of

items.

Mr. Silverman has “changed things

radically,” says Abby Glassenberg, president of the Craft Industry Alliance, a

professional group that represents craft makers and sellers of every kind. She’s

also been an Etsy seller since its very beginning, back in 2005, and has paid

close attention to its evolution.

|

Ms. McMinn

packages biscuits for shipping. Demand for her home-cooked baked goods

has skyrocketed lately.

PHOTO: ANDREW

SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL |

“He knows how to run a public

company and increase shareholder value. If that’s the goal, it’s undeniably

working, and it’s working during a pandemic,” she says.

Far from the Etsy corporate

headquarters, other changes have swept across the U.S., making home-baked goods

more commercially viable. From 2013 to 2018, 10 states passed so-called “cottage

food laws” allowing home bakers to legally sell their goods in a variety of

venues, including online, says Emily Broad Leib, faculty director of the Harvard

Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic. Many other states amended existing food

laws.

While this wave of legislation was

driven by, and has enabled, a grass-roots movement of professional home bakers

who have found a natural home on Etsy, the company itself hasn’t done much to

encourage this category above others. Those who have been selling baked goods on

the site for years feel like the lack of promotion of Etsy’s many bakers shows

the company’s interests lie elsewhere. “I really hate feeling like the people

selling baked goods are the ugly stepchild,” says Ms. McMinn.

Nevertheless, the category has

exploded. The half-dozen bakers I talked to all reported increases in orders of

between 200% and 450% in the past two months, compared with a year ago. A

company spokeswoman said searches on Etsy for terms like “baked goods” and

“brownies” have roughly doubled in the past two months, compared with a year

ago. Searches on the site for related terms yield tens of thousands of items

from nearly as many sellers, everything from sourdough bread and gourmet

doughnuts to Keto-friendly waffles and alkaline tahini spelt cookies. The

company declined to offer numbers on the sale of food items.

Like just about every e-commerce

company on this pandemic-stricken space rock, Etsy is benefiting from the fact

that people still want to buy stuff but, for the past couple of months at least,

are unable

to visit conventional retail outlets. The e-commerce divisions of Amazon and Walmart have

been overwhelmed by record

demand, Instacart has pledged to hire hundreds

of thousands of new personal shoppers, and FedEx has had to

cap shipments

from stores.

|

|

|

Some of the ingredients Ms. McMinn uses in her baking come from her own

West Virginia farm. PHOTOS: ANDREW SPEAR FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL(2) |

But Etsy has proved to have

strengths that would have been difficult to anticipate, says Ms. Glassenberg.

For one, its suppliers generally already work at home, so lockdown didn’t affect

their ability to be productive, as long as they were able to get raw materials.

For another, while both eBay and Amazon offer handmade goods, sellers who have

sold at all three of these outlets say Etsy is their preferred marketplace. Etsy

customers are willing to accept higher prices than eBay customers, and Amazon

prioritizes sellers who can ship goods quickly, which isn’t always possible for

solopreneurs producing on demand.

Besides, shoppers find comfort in

buying food from producers who seem like real people they can relate to and

trust—which Etsy

does better than Amazon, for one.

The Etsy bakers I’ve spoken with are

tired but, to a person, glad to have a marketplace for their goods. And in a

time of pandemic, it’s not just the ability to make a living they are grateful

for. On a site that encourages customers to message sellers, bakers say they’re

chatting with buyers more than ever.

“One lady ordered scones and put a

note on her order to please put nothing on the outside of the box that revealed

there was food inside,” says Ms. McMinn. “She said, ‘Life is hard right now and

I don’t want to share.’”

Write to Christopher

Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com