|

Forum reference:

Legal experts' failure to distinguish between

investor definitions of market pricing and intrinsic value in appraisal analyses

|

For the cases on which this

series of articles (in parts 1, 2

and 3, below) focuses, see

|

|

Sources

Part 1:

Law360, July 28, 2015 article

Part 2:

Law360, July 29, 2015 article

Part 3:

Law360, July 30, 2015 article |

A Study Of Recent Delaware Appraisal

Decisions: Part 1

|

|

Philip Richter |

|

|

Robert C. Schwenkel

|

Law360, New

York (July 28, 2015, 4:38 PM ET) -- There has been much ado about the

Delaware Chancery Court’s recent reliance on the merger price to determine

fair value in appraisal cases.

The Delaware statute defines fair value of a company as its going-concern

value immediately prior to the merger, excluding value arising from the

merger itself. In the past, the court has relied on standard financial

analyses of going-concern value (primarily discounted cash flow (DCF) and

comparable companies or transactions analyses). In a break with past

practice, however, several times in recent months, the court has relied

primarily or exclusively on the merger price to determine fair value.

The Court’s Reliance

on the Merger Price is Still Limited

Narrow Set of Circumstances (Two-Prong Test). The court has

emphasized that it will rely primarily on the merger price only when both

(1) the merger price is particularly reliable as an indication of value

because an effective market check was part of the sale process and (2) the

financial valuation methodologies are particularly unreliable because the

available inputs — projections and comparable companies or transactions —

are unreliable.

Small Number of Cases. There have been only four cases in

which the court has relied primarily on the merger price.

Factual Context. The factual context in each of these cases

included (1) an especially strong sale process — a public auction with

competing bids in three of the four cases and, in the fourth case, a

thorough public shopping of the company to obtain a white knight bidder

(although no competing bid emerged); (2) no competing bid being made after

announcement of the merger; and (3) a merger price that represented a

significant premium above the unaffected stock price.

The Court’s Approach

Has Been Consistent in the Appraisal Decisions This Quarter

The court’s appraisal decisions this past quarter have produced varying

outcomes — with the court determining fair value to be:

-

equal to the merger price — in Merlin v. Autoinfo (Apr. 30, 2015);

-

slightly below the merger price — in Longpath v.

Ramtron (June 30, 2015); and

-

significantly above the merger price — in Owen v. Cannon (June 17,

2015).

The court’s

approach has been consistent, however. In AutoInfo and Ramtron, both of

which involved arm’s length transactions with an effective market check

and with unreliable valuation analysis inputs (as well as a merger price

that represented a significant premium to the unaffected stock price), the

court relied primarily on the merger price — and found fair value to be

equal (or very close) to the merger price.

In Cannon, which involved an interested transaction (a squeeze-out merger)

with no market check (as well as a merger price well below the value

indicated by third-party valuations received by the company), the court

relied on a DCF analysis — and its fair-value determination represented a

60 percent premium over the merger price. It remains to be seen to what

extent the court may expand its use of the merger price as the primary

factor in determining fair value.

Before the court ever expressly used the merger price to determine fair

value, the court, stating that it was relying on DCF analyses,

consistently determined fair value to be equal or close to the merger

price in disinterested transactions in which there had been an effective

market check (and often determined fair value to be significantly higher

than the merger price in interested transactions without a market check).

Thus, while not expressly relying on the merger price, the actual results

of the court’s past appraisal decisions clearly suggest that, when there

has been an effective market check, the merger price has always been a

strong (albeit unacknowledged) factor in the court’s considerations.

Open Issues

Will the court’s increased inclination to use the merger price to

determine fair value expand to include any transaction with an effective

market check, whether or not there are reliable inputs for a financial

analysis?

So far, the court has used the merger price as the primary or exclusive

basis for determining fair value only in those cases involving

transactions that meet both prongs of the test noted above (an effective

market check and unavailability of reliable inputs for financial

analyses). Yet, reliance on the merger price whenever there has been an

effective market check — thus, even if, for example, the company

projections are reliable — no doubt holds allure. That approach would

short-cut the considerable difficulties inherent in a DCF analysis.

A DCF analysis can yield widely varying results depending on the selection

of the numerous required inputs for the analysis. These inputs are often

uncertain or subjective (including, for example, the company’s long-term

projections and the appropriate discount rate). Moreover, a small change

in any of them can yield a significant change in the result. Even when a

DCF analysis is conducted in a cooperative, nonlitigation context, there

may be considerable uncertainty about the reliability of the result — and

the court has often expressed frustration, most recently in Ramtron, with

“litigation-driven valuations” submitted by the parties’ experts.

Moreover, as noted, the results, as a practical matter, would not

necessarily differ from those that now pertain.

How strong would the market check have to be for the court to use

the merger price to determine fair value in a case involving an interested

transaction?

To date, the appraisal cases involving interested transactions have

included, in the court’s view, no (or weak) market checks. Moreover, the

amount by which the court’s fair value determinations (using financial

valuation analyses) have exceeded the merger price has generally

corresponded to the apparent strength of the sale process (even though the

process is logically irrelevant to a DCF or other financial analysis of

going-concern value). It remains to be seen whether the court would accord

to an interested transaction with an effective market check the same

treatment as a disinterested transaction with an effective market check.

Would the merger price or the financial valuation take precedence in

the case of a transaction in which there had been an effective market

check but also reliable financial analyses — and the financial valuation

exceeds the merger price?

If the court were to expand its use of the merger price to all

transactions with an effective market check, how would the court respond

if the financial valuations — if based on reliable company projections and

sufficiently comparable companies and transactions — lead to values

materially in excess of the merger price? Clearly, in such a case, either

the “effective market check” would not in fact have been effective or

there would have been a “market failure” for some reason. Presumably, the

course the court would choose in these circumstances would depend on the

court’s view of the reason for the discrepancy between the merger price

and the financial valuations.

Key Points

-

Consistency of Results in

Appraisal Cases.

The court has been, and continues to be, consistent in awarding

appraisal amounts equal (or close) to the merger price in disinterested

transactions in which the sale process included an effective market

check — whether the court has utilized the merger price or a DCF

analysis as the basis for determining fair value. The court continues to

be consistent in awarding appraisal amounts that significantly exceed

the merger price only in interested transactions without an effective

market check.

-

Use of the Merger Price Under

Narrow Circumstances.

Although the court has now relied on the merger price as the sole or

primary basis for determining value in four recent cases, in each of

these cases there was not only (1) an effective market check, but also

(2) the court viewed the standard financial analyses (DCF and

comparables analyses) as being particularly unreliable because

management projections were deemed to be unreliable for a variety of

reasons and there were not sufficiently comparable companies or

transactions.

-

Effect of Increased Use of

the Merger Price.

As noted, the court’s

increased used of the merger price in disinterested transactions with an

effective market check may not change the results in these cases.

Further, in our view, the increased use of the merger price may or may

not discourage appraisal arbitrage overall but, in any event, should

tend to drive appraisal claims away from disinterested transactions with

an effective market check (unless accompanied by indications that the

market check was not in fact effective) and to those transactions with

the most potential for an award significantly above the merger price.

-

Effectiveness of Market Check

When There is a Single Bidder.

The court has viewed a public auction process with competitive bidding

as an effective market check that supports the court’s use of the merger

price to determine appraised fair value. In Ramtron, even though no

competing bid emerged during the company’s search for a white knight

buyer after the company had received an unsolicited bid, the court

viewed the company’s “lengthy” and “public” shopping of the company

(during which it contacted every party that the company believed might

be interested) to have been an effective market check.

-

Continued Confusion About

Adjustments to Exclude Merger-Specific Value.

The court’s more frequent use of the merger price to determine fair

value necessarily focuses more attention on the long-neglected issue of

adjustments to the merger price to exclude merger-specific value from

the appraisal award (as is statutorily mandated). In AutoInfo, the court

articulated a new burden of proof that has the potential to provide

effective guidance to parties seeking to establish the need for an

adjustment. Although inconsistent with the general approach in appraisal

cases of both parties and the court itself having a burden to establish

fair value, the court stated that the party arguing for an adjustment to

exclude value arising from merger-specific synergies would have the

burden of establishing the merger-specific nature of the synergies and

their value. We note that, nonetheless, the next appraisal decision,

Ramtron, indicates that, where both parties propose an adjustment

amount, the court may select the amount it considers to be more

reasonable (which the court in Ramtron did without analysis or much

explanation), even if the burden of proof has not been met. We note that

the court still has not addressed (and parties to appraisal actions

still have not raised) the issue of whether all or part of a control

premium included in the merger price is merger-specific value that

should be excluded.

-

Reliability of Projections —

No Change in the Court’s Approach.

The court continues to find projections to be unreliable when they are

not prepared by management in the ordinary course of business.

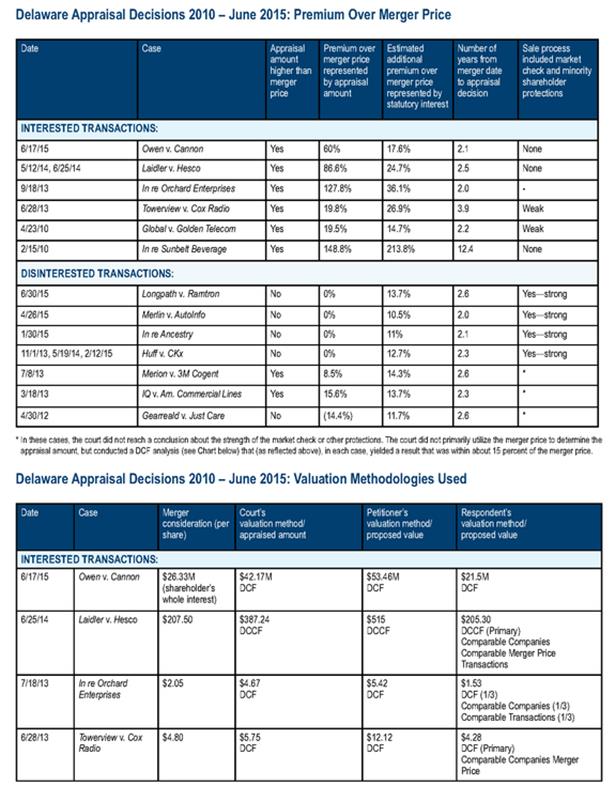

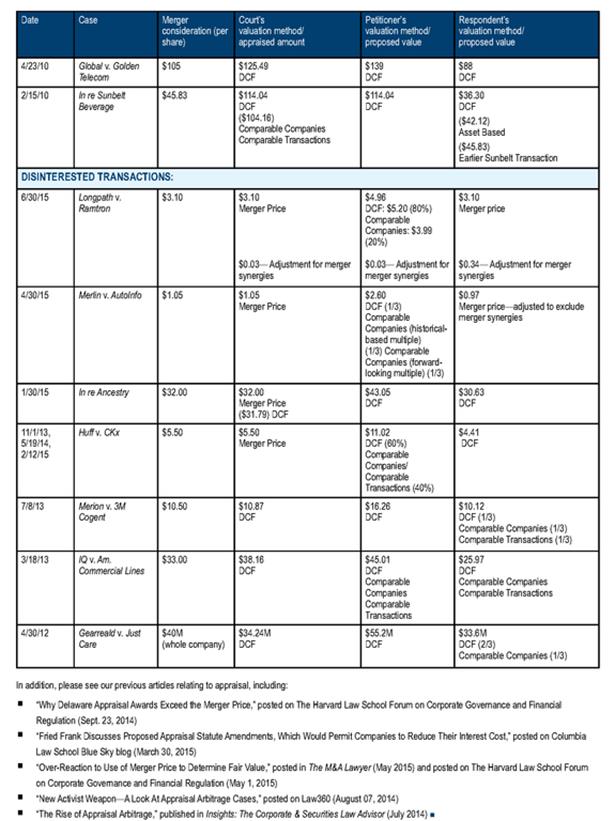

Please see

below our charts summarizing the outcome of each appraisal case since 2010

and a list of our other articles on appraisal.

Parts 2 and 3 of this article will be published here in the coming days,

covering additional explanation and discussion of the key points noted

above; summaries of AutoInfo, Cannon and Ramtron; and practice points

relating to adjustments to the merger price, projections and other

appraisal-related issues arising out of these decisions.

—By Steven Epstein, Arthur Fleischer Jr., Peter S. Golden, Brian T.

Mangino, Philip Richter, Robert C. Schwenkel, John E. Sorkin and Gail

Weinstein,

Fried Frank Harris Shriver & Jacobson LLP

Steven Epstein,

Peter Golden,

Philip Richter,

Robert Schwenkel and

John Sorkin are partners in Fried

Frank's New York office.

Brian Mangino is a partner in

Washington, D.C.

Arthur Fleischer and

Gail Weinstein are senior counsel in

New York.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or

any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general

information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as

legal advice.

|

A Study Of Recent Delaware Appraisal

Decisions: Part 2

|

|

Steven Epstein |

|

|

John E. Sorkin

|

Law360, New

York (July 29, 2015, 4:38 PM ET) -- In

part 1 of this article, we outlined

the key points relating to the latest Delaware appraisal decisions: Merlin

v. Autoinfo (Apr. 30, 2015), Owen v. Cannon (June 17, 2015), and Longpath

v.

Ramtron (June 30, 2015). Specifically,

we noted that, although the Chancery Court in recent months has expanded

its use of the merger price in the underlying transaction as a basis for

determining appraised “fair value,” the court’s reliance on the merger

price has been expressly limited to a narrow set of circumstances. We

noted further that, at the same time, while the most recent appraisal

decisions have resulted in varying outcomes — with the court determining

fair value to be equal to the merger price (in Merlin), significantly

above the merger price (in Cannon), and slightly below the merger price

(in Ramtron) — the court’s approach has been consistent.

In this article, we provide further explanation and discussion of the key

points arising out of AutoInfo, Cannon and Ramtron. Part 3 of this article

will be published here in the coming days, covering practice points

arising out of these decisions.

Consistency of the Chancery

Court's Results in Appraisal Awards

Interested Transactions Without an Effective Market Check

The court has been consistent in determining fair value to be

significantly above the merger price only in interested transactions

(i.e., transactions involving, for example, a controller or a

parent-subsidiary or squeeze-out merger) without an effective market

check. Moreover, the amount of the premium above the merger price

represented by the fair-value determination in these cases has

corresponded with the extent of the market check. The premiums in cases

involving interested transactions that included no market check ranged

from 60 percent to 150 percent, while the premiums in cases involving

transactions that included some (albeit, in each case, a weak) market

check were just under 20 percent.

Disinterested Transactions with a Market Check

Irrespective of the valuation methodology utilized by the court, the court

has been consistent in determining fair value to be not significantly

above the merger price in disinterested transactions with a market check.

In the disinterested transactions that have included an effective market

check, the court has determined fair value to be equal (or close) to the

merger price. In the disinterested transactions in which the court did not

comment on the sale process (although, we note, in each of these there

appeared to be no, or only a weak, market check), the court has determined

fair value to be above, but not significantly above, the merger price

(specifically, premiums of 9 percent and 16 percent above the merger

price, and, in one case with an unusual fact situation, 14 percent below

the merger price).

Methodology to Determine

Fair Value

The Delaware appraisal statute defines fair value for appraisal purposes

as going-concern value of a company immediately preceding the merger,

excluding any value arising from the merger itself.

Use of the Merger Price

The court now primarily or exclusively relies on the merger price to

determine fair value when (1) the merger price is a particularly reliable

indication of value because it has been established through a sale process

that included an effective market check and (2) the standard financial

valuation analyses (discounted cash flow (DCF) and comparables analyses)

are particularly unreliable because (a) the available company projections

(the primary input for a DCF analysis) are unreliable and (b) there are

not sufficiently comparable transactions or companies (for meaningful

input to a comparables analysis). All of the recent cases meeting these

parameters have involved disinterested transactions.

Use of DCF Analysis

In the case of interested transactions, and in the case of disinterested

transactions in which either prong of the two-part test has not been

satisfied, the court has relied primarily or exclusively on a DCF analysis

to determine appraised fair value. As noted, in these cases,

notwithstanding the potential inherent in a DCF analysis for wide

variability of the results, and notwithstanding the logical irrelevance to

a DCF analysis of the nature of the transaction or the sale process, the

court’s results have been significantly above the merger price in the case

of interested transactions and not significantly above the merger price in

the case of disinterested transactions (with the amount of any premium

above the merger price corresponding to the apparent strength of the sale

process).

Open Issues

We note that key open issues remaining include: Will the court’s increased

inclination to use the merger price to determine fair value expand to

include any transaction with an effective market check, whether or not

there are reliable inputs for a financial analysis? How strong would the

market check have to be for the court to use the merger price to determine

fair value in a case involving an interested transaction? Would the merger

price or the financial valuation take precedence in the case of a

transaction in which there had been an effective market check but also

reliable financial analyses — and the financial valuation exceeds the

merger price?

Effectiveness of Market

Check

Prior to Ramtron, each case in which the court utilized the merger price

to determine fair value after finding that there had been an effective

market check involved a public auction with competing bids. In Ramtron,

the court viewed the company’s aggressive public shopping of the company

to find a white knight buyer to be an effective market check — even though

no competing bidder emerged. Notably, the $3.10 merger price the company

ultimately agreed with the unsolicited bidder, after five separate price

increases, represented a 71 percent premium over the unaffected stock

price and a 25 percent increase over the unsolicited bidder’s initial

offer price. The court found that the nonemergence of competing bids was a

result of the company’s “operative reality” rather than “any shortcomings

of the process.” The court noted that no party made a competing bid even

at the time that the unsolicited bidder’s offer was 42 cents below the

final merger price.

Continued Uncertainty About

Adjustments to the Merger Price to Exclude Merger-Specific Value

The Delaware appraisal statute mandates that any value arising from the

merger itself be excluded from appraised fair value. In the cases in which

the court has utilized the merger price as a basis for fair value, the

court has acknowledged that merger-specific value must be “backed out.”

However, the court invariably has not made adjustments — sometimes simply

ignoring the issue and sometimes indicating that the parties had not

argued for or established a sufficient basis for an adjustment.

There are difficulties inherent in determining what is a merger-specific

synergy and how to calculate the value it represents. These difficulties,

as a practical matter, may account for the court’s reluctance to make

adjustments to exclude merger-specific value when the merger price is used

as the primary or sole basis for determining fair value.

Further, the court has not addressed (and the parties to appraisal actions

have not raised) the complicated issue of whether all or part of a control

premium is merger-specific value that should be excluded from a

determination of fair value.

AutoInfo: Court Establishes a New Burden on the Party Advocating an

Adjustment for Merger Synergies

In AutoInfo, the court has provided what appears to be new, albeit

limited, guidance on this issue. The court placed on the party arguing for

an adjustment a burden to establish the need for, and amount of, the

adjustment. We note that, generally, the court has characterized the

appraisal statute as placing a burden on both parties and on the court to

determine fair value. Thus, no presumptions have been applied by the court

based on one or the other party’s failing to provide convincing evidence

with respect to one or more parts of the determination of fair value.

Rather, the court has viewed itself as having the burden of determining

whether to rely on one party’s view or the other’s or, if it finds neither

persuasive, than to form its own view. In AutoInfo, the court appears to

have departed from that approach in connection with the issue of

adjustments to the merger price when it is used as the basis for fair

value.

In AutoInfo, the respondent company’s expert had argued that a downward

adjustment should be made to the merger price to exclude the cost savings

the acquiror anticipated from eliminating public company costs and

reducing executive compensation. These savings were reflected in the base

case projections the acquiror had developed and used internally. Following

its usual course, the court did not make any adjustment to exclude

merger-specific synergies. The court stated that the record had not

established precisely the nature of the anticipated cost savings (thus,

according to the court, it could not be determined whether they were

merger-specific) or the reliability of the estimated amount of the

savings. The court, in effect, established a presumption against an

adjustment for anticipated cost savings unless the company demonstrates

that the anticipated savings are merger-specific and that the court can

have confidence in the amount.

It remains to be seen how rigorous a standard the court will apply in

determining whether a record sufficiently supports an adjustment being

made to the merger price. Given the court’s strong reluctance to date to

make any adjustments when the merger price has been used to determine fair

value, and given that the court rejected any adjustment in AutoInfo even

though the record (while not fully developed) appeared to be sufficient to

indicate that some adjustment would be required, we expect that the court

may continue to apply a restrictive standard.

Ramtron: Court Chooses Between Parties’ Proposed Adjustments

(Selecting Only a Nominal Adjustment)

In Ramtron, the court rejected the respondent’s two proposed methods of

determining an adjustment to exclude merger-specific synergies (both of

which indicated a 34 cents per share adjustment of the $3.10 merger

price). We note that, if the company had the benefit of the court’s

discussion of adjustments in AutoInfo, it may have been possible for the

company to have developed a more acceptable methodology. With little

discussion, the court characterized the petitioner’s proposed nominal

adjustment (3 cents per share) as “better conform[ing] to the evidence

adduced at trial” — even though, the court stated, that adjustment “may

understate” the merger-specific synergies.

The court noted the petitioner’s testimony that, in addition to “positive

synergies” anticipated from the merger (such as cost savings), significant

“negative synergies” (i.e., negative effects on revenue, as well as

transaction costs in the range of 10-15 percent of revenue) were also

expected. Therefore, the court appeared to believe that the petitioner’s

nominal adjustment (although likely too low) made more sense than the

respondent’s proposed significant adjustment (which, the court noted,

represented more than 10 percent of the merger price).

Notwithstanding the burden of proof established in AutoInfo, the court in

Ramtron simply selected what it viewed as the more reasonable of the two

proposals, without regard to the burden of proof. In our view, it may be

that the court will take this approach only in limited situations — such

as where, as was the case in Ramtron, significant negative synergies are

anticipated, both parties propose adjustment amounts, one amount does not

take into account the negative synergies, and the other amount is nominal.

Reliability of Projections —

No Change in the Court’s Approach

The court generally views as reliable projections that are prepared by

management in the ordinary course of business. These are viewed as

reliable because management ordinarily has the best first-hand knowledge

of a company’s operations and, when prepared in the ordinary course, the

projections typically reflect management’s best estimate of the company’s

future performance and are not tainted by distorting influences or

post-merger hindsight.

The court has viewed management projections as unreliable when they:

-

were prepared outside the

ordinary course of business;

-

were prepared by a management

team that never before prepared similar projections;

-

were prepared in anticipation

of litigation or an appraisal action, or with some other motive (for

example, to protect their jobs or to increase the apparent value of the

company in a sale process);

-

were viewed by management

itself as unreliable; and/or

-

were based on unusual company

or industry factors that were so speculative as to make forecasting

nearly impossible.

AutoInfo

and Ramtron: Unreliable Projections

In Ramtron and AutoInfo, the court rejected use of a DCF analysis to

determine fair value in part because the court deemed the management’s

projections to be unreliable.

In Ramtron, the court deemed the projections to be unreliable because they

were prepared by a new management team (with the CEO, chief financial

officer and all other senior management having been at the company for

less than two years); the team used a new methodology (that the team

appeared to view, without confidence, as a “new and unfamiliar process”);

and the company had previously only ever prepared short-term forecasts

(which the company itself had recently characterized as having limited

reliability).

Further, the court found that the projections, prepared while the company

was in the process of trying to defend against a hostile takeover bid,

were prepared in anticipation of possible future disputes and seeking

white knights; in addition, the projections did not accord with the

reality of the business in numerous respects. Moreover, the company itself

did not rely on the projections in the ordinary course of its business

(having prepared other projections for managing the company’s finances,

including providing information to the company’s bank). Importantly, the

court criticized the parties’ “litigation-driven” valuations, including

the petitioner’s “eyebrow-raising DCF,” which relied on projections the

expert had presumed were overly optimistic and yet still yielded a result

2 cents below the merger price.

In AutoInfo, the court found that the company’s projections were

unreliable because management had been specifically directed to “paint an

‘aggressively optimistic’ picture” for the purpose of generating more

interest in, and a better price for, the company in its sale process. In

addition, management had never before prepared projections, “had no

confidence in its ability to forecast” the company’s future performance,

and “perceived its attempt [to forecast] as ‘a bit of a chuckle and a

joke.’”

Cannon: High Bar for Company to Disavow Its Projections

In Cannon (an interested transaction), the court and both of the parties

utilized a DCF analysis to determine fair value. The court rejected the

company’s attempt to disavow the projections that had been prepared by the

company’s president in favor of projections later created by the company’s

expert. The expert’s projections, which had been prepared in anticipation

of a mediation of the parties’ dispute with respect to the forced buyback

of the petitioner’s shares, projected less growth in the company than the

projections that the company had prepared earlier in anticipation of

offering to buy back the petitioner’s shares. The court deemed the

expert’s projections to be unreliable because they were prepared in

anticipation of litigation.

While the president’s projections had been prepared for the purpose of

determining the offer price for the contemplated forced buyback of the

petitioner’s shares (either through his agreement or a squeeze-out

merger), the petitioner did not argue that they were unreliable on this

basis, but argued instead that the president’s projections were more

reliable than the expert’s revised projections.

The court agreed, finding that the following factors supported the

reliability of the president’s projections: (1) although the projections

had not been prepared by a management team but by the president alone, the

president had a thorough knowledge of the company and its prospects, and

other management input was obtained through weekly discussions with the

president about results, developments and prospects; (2) the president

had, over a three-year period, updated and revised the projections to

reflect actual results and new developments; (3) the president had

submitted the projections to financing sources (here, the court emphasized

that it will place great weight on projections that have been provided to

financing sources, as it is a federal felony to knowingly obtain funds

from a financial institution by false or fraudulent pretenses or

representations); and (4) it was unlikely that the president’s projections

were too high, as he had an incentive to make the projections as low as

possible since they were prepared for the purpose of setting the price for

the buyback of the petitioner’s shares.

The court rejected the respondent’s arguments that, based on principles

discussed in previous Chancery Court decisions, the projections prepared

by its president were unreliable. The court distinguished the previous

decisions as follows:

-

CKx.

In Huff v. CKx (2013), the court viewed the company’s projections as

unreliable because a projected increase in licensing fees under a

material, to-be-negotiated contract was so speculative and the initial

estimates of those revenues had been markedly lower than the projections

provided to potential buyers and lenders. By contrast, the court noted,

in Cannon, although Cannon had argued that its prospects had dimmed, it

had not identified any particular line item or line of business in the

projections that was so uncertain as to undermine the integrity of the

overall projections.

-

JustCare.

In Gearreald v. Just Care (2012), the court viewed the company’s

projections as unreliable because the company had never before prepared

multiyear projections. The court distinguished the situation in ESG by

noting that, even though the company had not generally prepared

projections in the ordinary course of business, the president’s

projections had been prepared (and updated and revised) over three

years; that he had been confident enough in them to provide them to

banks in connection with financing the buyout; and that they had been

created in part with the assistance of a financial adviser with whom the

president had reviewed the revenue growth assumptions.

-

Nine Systems.

In In re Nine Systems (2014), the court viewed a set of one-year

projections as unreliable because the projections were inconsistent with

the company’s recent performance (specifically, management had

“overestimated ... revenues even two months away ... by more than a

factor of three”). By contrast, in Cannon, the court noted, the

company’s performance in the months just preceding the merger was in

line with the projections.

Summary of Most

Recent Cases: AutoInfo, Cannon and Ramtron

AutoInfo — In this disinterested transaction involving a

competitive public auction, the court:

-

used the merger price to

determine fair value (with a DCF analysis as a double-check);

-

found the sale process to

have been thorough;

-

found the management

projections unreliable because they were prepared with a view to

marketing the company;

-

imposed a new burden with

respect to adjustments to the merger price to exclude merger-specific

synergies; and

-

determined fair value to be

equal to the merger price.

In AutoInfo,

the merger price, $1.05 per share, had been established through a public

auction process conducted at arm’s length by a special committee with an

independent financial adviser. The company and its financial adviser had

aggressively shopped the company; the merger agreement was entered into

with the bidder that had by far the highest indication of interest

(although, after that bidder uncovered alleged accounting, financial and

other irregularities during due diligence, the price was renegotiated to

an amount slightly below the amount at which some of the other indications

of interest had been); and no competing bid emerged during the almost

two-month post-signing period. The court rejected the company’s

projections as unreliable because management had been instructed to

prepare aggressively optimistic projections as they would be used to

market the company. The court rejected the petitioner’s comparable

companies analysis because of the much larger size of the companies

included and their different business model (store-based as opposed to the

company’s agent-based model).

The petitioner’s expert had argued that fair value was $2.60 per share,

based one-third each on a DCF analysis, comparable company analysis using

a historical-based multiple, and a comparable company analysis using a

forward-looking multiple. The respondent’s expert had argued that fair

value was 97 cents, based on the merger price, adjusted downward to

exclude cost savings arising from the merger. The court based fair value

on the merger price — and also conducted its own DCF analysis as a

double-check on the merger price (which yielded a result slightly below

the merger price: 93 cents). The court rejected any adjustment to the

merger price to exclude merger-specific synergies, reasoning that the

party arguing for those adjustments (the company) had a burden (that it

had not met) to establish the nature and amount of the synergies alleged

to be merger-specific before any adjustment could be made.

Cannon — In this interested transaction involving a

squeeze-out merger at a price far below the value indicated in third-party

valuations received by the company (and with no market check), the court:

-

used a DCF analysis to

determine fair value (as had both parties);

-

rejected the company’s

attempt to disavow (and lower) its projections; and

-

determined fair value to be

significantly higher than the merger price.

In Cannon, two

stockholder-directors of a Subchapter S corporation forcibly removed the

third stockholder-director (the petitioner) as president and, after

several failed attempts at repurchasing his shares, effected a squeeze-out

merger in which his shares were canceled. At the merger price, the

petitioner would have received $26.33 million for his interest. The

repurchase offers and the merger price for his interest were all far below

the value indicated in third-party valuations received by the company

throughout the relevant periods. The court utilized a DCF analysis to

determine fair value, yielding a result of $42.17 million — representing a

60 percent premium over the merger price. The result of the DCF analysis

conducted by the petitioner’s expert was $53.46 million, while the

respondents’ expert’s DCF result was $21.50 million. The difference in

results in the DCF analyses was primarily attributable to the different

projections utilized.

In addition, the petitioner had tax-affected the company’s earnings in the

analysis to compensate the petitioner for the loss of the tax advantage in

being a stockholder of a Subchapter S corporation. The court utilized the

projections prepared by the company’s new president (one of the two

stockholder-directors who planned the merger), rejecting the respondents’

arguments that their expert’s more conservative projections should be used

instead, and agreed with the petitioner that the Subchapter S corporation

earnings should be tax-affected.

Ramtron — In this disinterested transaction involving a

hostile takeover bid and a thorough search for a white knight buyer (with

no competing bidder having emerged), the court:

-

used the merger price to

determine fair value;

-

found the management

projections unreliable for a variety of reasons;

-

made a nominal adjustment to

the merger price for merger-specific synergies (without much

discussion); and

-

based on the nominal

adjustment, determined fair value to be just below the merger price.

In Ramtron, the company, after receiving an unsolicited bid, aggressively

shopped the company to find a white knight buyer, while rejecting the

unsolicited bid. No competing bids emerged over the three-month period and

the company ultimately agreed to a merger with the unsolicited bidder. The

merger price, $3.10 per share, represented a 75 percent premium over the

unaffected stock price and, after five separate increases in the bid

price, a 25 percent increase from the initial offer. The court rejected

the management projections as unreliable because, among other things, the

entire senior management team had been in place for a very short time; the

projections were prepared using a new methodology; the management

expressed uncertainty about the reliability of the projections and used

different projections to manage the company’s finances and provide

information to its bank; and the projections were prepared in anticipation

of potential litigation (including an appraisal action). The court

rejected the petitioner’s comparables analysis because it was comprised of

only two comparable companies and the multiples for each differed

significantly, making the average of the data points unreliable.

The petitioner’s expert had argued that fair value was $4.96 per share

(which was 274 percent of the unaffected stock price, the court noted),

based 80 percent on its DCF analysis (which yielded a result of $5.20) and

20 percent on its comparables analysis (which yielded a result of $3.99).

The respondents’ expert had argued that fair value was $2.76, based on the

merger price, adjusted downward to exclude cost savings arising from the

merger. The respondent’s expert argued, in the alternative, that fair

value, based on a DCF analysis utilizing management’s projections, was

$3.08. The court based fair value solely on the merger price and, with

little analysis or explanation, adjusted the merger price downward by the

3 cents that the petitioner proposed represented the merger-synergy

savings less the merger-synergy costs.

Please see

part 1 of the article for our charts

summarizing the outcome of each appraisal case since 2010 and a list of

our other articles on appraisal. Part 3 of this article, to be published

here in the coming days, will cover practice points relating to

adjustments to the merger price, projections and other appraisal-related

issues arising from AutoInfo, Cannon and Ramtron.

—By Steven Epstein, Arthur Fleischer Jr., Peter S. Golden, Brian T.

Mangino, Philip Richter, Robert C. Schwenkel, John E. Sorkin and Gail

Weinstein,

Fried Frank Harris Shriver & Jacobson LLP

Steven Epstein,

Peter Golden,

Philip Richter,

Robert Schwenkel and

John Sorkin are partners in Fried

Frank's New York office.

Brian Mangino is a partner in

Washington, D.C.

Arthur Fleischer and

Gail Weinstein are senior counsel in

New York.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or

any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general

information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as

legal advice.

|

A Study Of Recent Delaware Appraisal

Decisions: Part 3

|

|

Philip Richter |

|

|

Brian T. Mangino

|

Law360, New

York (July 30, 2015, 10:28 AM ET) -- In

part 1 of this article (published July

28), we outlined the key points relating to the latest Delaware appraisal

decisions: Merlin v. Autoinfo (Apr. 30, 2015), Owen v. Cannon (June 17,

2015), and Longpath v.

Ramtron (June 30, 2015). Specifically,

we noted that, although the Chancery Court in recent months has expanded

its use of the merger price in the underlying transaction as a basis for

determining appraised “fair value,” the court’s reliance on the merger

price has been expressly limited to a narrow set of circumstances. We

noted further that, at the same time, while the most recent appraisal

decisions have resulted in varying outcomes — with the court determining

fair value to be equal to the merger price (in AutoInfo), significantly

above the merger price (in Cannon), and slightly below the merger price

(in Ramtron) — the court’s approach has been consistent. In

part 2 of this article (published July

29), we provided further explanation and discussion of the key points

arising out of, as well as summaries of, AutoInfo, Cannon and Ramtron. In

this part 3, we provide practice points arising out of these decisions.

Key Practice Points for

Acquirors Relating to Adjustment of the Merger Price

Establish the Amount and Nature of the Expected Cost Savings

An acquiror should outline in some detail the cost savings expected from

the merger. References to anticipated savings embedded, for example, in

assumptions for projections or in an investment memorandum may not be

sufficient. The acquiror should identify what portion of the expected

savings is attributable to the merger itself.

For example, executive compensation reductions that are anticipated due to

the overlaps of executive positions at both companies (i.e., the merged

company will not need two CEOs, two chief financial officers, etc.) would

appear to be merger-specific. Reductions that are anticipated due to the

target’s already having implemented compensation reductions would not be

merger-specific. Reductions anticipated because the target’s compensation

scale is above market (so reductions could be achieved by the target

itself without the merger, but the target might not have thought of or

wanted to make those reductions) are more difficult to classify as

merger-specific or not.

The acquiror should consider identifying what part of its offer price is

based on expected merger-specific cost savings. Internal documents, and

those prepared by the company’s investment banker, should be carefully

reviewed so as to be consistent with the acquiror’s views of

merger-related cost savings.

Consider Establishing the Amount of the Control Premium

The merger price typically includes a control premium, all or part of

which logically is merger-specific and should be excluded from the court’s

determination of fair value. An acquiror should consider establishing a

foundation to support a determination as to what part of the merger price

is represented by a control premium. If the merger price is used to

determine fair value in an appraisal proceeding, the respondent company

should argue for a downward adjustment to exclude that amount. We are not

aware of parties to appraisal proceedings having made this argument and

the court has not addressed the issue. (Of course, the calculation of the

control premium amount could be complex because, for example, part of a

control premium may be attributable to merger synergies (and cannot be

counted twice in determining reductions).

Seek to Understand the Target Company’s Sale Process

The acquiror will have a better sense of the likely appraisal risk if it

understands the target’s sale process, including whether there was an

effective market check. The acquiror should consider requesting

information about the sale process from the target company’s general

counsel and seeking to review a draft of the target’s description of the

background of the transaction in its proxy statement or tender offer

statement.

Seek to Establish the Nature and Reliability of the Target’s

Projections

The acquiror will have a better sense of the likely appraisal risk if it

understands the target’s process in developing its projections. For

example, the acquiror should seek to understand: Does the company prepare

annual projections on a regular basis? What is the nature of those

projections (one-, three- or five-year)? Are the projections subject to

review by the board and what is the extent of the review? Were the

projections utilized in the sale process prepared in the ordinary course?

Are there any factors indicating that the projections utilized in the sale

process were prepared other than in the ordinary course? Are there any

factors indicating that the projections were modeled to be “aggressively

optimistic,” were prepared in anticipation of the sale process, or do not

reflect the management’s best view of the company’s future? What has

management said about its confidence in the projections and how has

management used the projections? Have the projections been provided to the

company’s banks or other financial institutions?

We note that, if a court utilizes the merger price to determine fair value

and requests adjustment proposals from the parties, the petitioner and the

company may wish to consider the game theory involved in proposing a lower

proposed adjustment (in the case of the company) or a nominal proposed

adjustment (in the case of the petitioner) insofar as it may affect the

court’s decision whether to reject both proposals as not satisfying the

burden of proof or to select what it views as the more reasonable between

the two proposals.

Key Practice Points From

Cannon

Stockholders Agreement Should Have Prevented the Squeeze-Out Merger

The petitioner argued that the merger violated the stockholders agreement

among the petitioner and the other two stockholders. That agreement

required that all three stockholders approve any “agreements or

transactions valued in excess of [$10,000]” and “any material changes in

the business of the Company.” The court declined to resolve the issue for

various reasons. We note, however, that the stockholders agreement could

have been drafted more clearly to prevent a squeeze-out merger or other

forced buyout of any of the stockholders by the other two (or to provide

certain protections in that event).

Valuations and Offers to Purchase Prior to a Squeeze-Out

The company’s credibility was damaged by its several offers to purchase

the petitioner’s stock at prices, in each instance, significantly below

the value of the petitioner’s shares indicated by third-party valuations

the company had received.

Key Practice Point for

Bankers Relating to DCF Analysis

No Liquidity Discount to Cost of Capital Size Premium

In AutoInfo, the court indicated that, in a DCF analysis for appraisal

purposes, the weighted average capital cost (WACC) component of the

capital asset pricing model (CAPM) should generally be calculated without

applying any “marketability” or “illiquidity” discount to the equity size

premium derived from the Ibbotson tables. The court indicated agreement

with the position, taken in Gearreald v. JustCare (2012), that, as “the

‘liquidity effect’ contained within the size premium” relates to the

company’s ability to obtain capital at a certain cost, it is therefore

related to the company’s intrinsic value as a going concern, and should

therefore be included in the calculation of its cost of capital in a DCF

analysis for appraisal purposes.

Hypothetical Corporate-Level Tax Rate for Subchapter S Corporation

According to the court in Cannon, determining the corporate-level tax rate

to calculate the company’s projected free cash flows, a hypothetical rate

must be determined for an S corporation that “treats the S corporation

shareholder ... as receiving the full benefit of untaxed dividends, by

equating [his] after-tax return to the after-dividend return to a C

shareholder.”

—By Steven Epstein, Arthur Fleischer Jr., Peter S. Golden, Brian T.

Mangino, Philip Richter, Robert C. Schwenkel, John E. Sorkin and Gail

Weinstein,

Fried Frank Harris Shriver & Jacobson LLP

Steven Epstein,

Peter Golden,

Philip Richter,

Robert Schwenkel and

John Sorkin are partners in Fried

Frank's New York office.

Brian Mangino is a partner in

Washington, D.C.

Arthur Fleischer and

Gail Weinstein are senior counsel in

New York.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or

any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general

information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as

legal advice.

© 2015, Portfolio Media, Inc. |

|

|