|

|

|

MICHAEL DELL ISN'T COMPLAINING. PHOTOGRAPHER: JUSTIN

SULLIVAN/GETTY IMAGES. |

| |

|

| |

Matt Levine is a Bloomberg View

columnist writing about Wall Street and the financial world.

Levine was previously an editor of Dealbreaker. He has worked as

an investment banker at Goldman Sachs and a mergers and

acquisitions lawyer at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. He spent

a year clerking for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit and taught high school Latin. Levine has a bachelor's

degree in classics from Harvard University and a law degree from

Yale Law School. He lives in New York. |

Wall Street

T. Rowe Price Voted for the Dell Buyout by Accident

MAY 13, 2016 12:14 PM EDT

By

Matt Levine

Sometimes companies are acquired by

other companies. The way this works is that the target company's

managers and board negotiate a deal with the acquirer, and then they

call a meeting where the shareholders can vote on the deal. They book

a big room, and the shareholders show up, and the managers say why the

deal is good, and the shareholders discuss it for a bit, and then they

vote. This is a real thing that actually happens. I went to one once.

But usually it is more complicated than that. Mostly, it is

inconvenient for shareholders to show up at the meeting, so mostly

they don't. Companies mail out proxy cards, and if you are a

shareholder with better things to do that day, you fill out the proxy

card and mail it back. The proxy card appoints someone who'll be at

the meeting anyway -- typically someone who works for the company --

to vote on your behalf.[1]

You tell her how to vote, and then she does it,

and it's as though you'd been there and voted yourself. You don't even

have to pay postage; the company provides a self-addressed stamped

envelope.[2]

But usually it is more complicated than

that. Most shareholders in most companies are not actually

shareholders in those companies. That is, they are not "shareholders

of record," who own shares that are reflected on the stock registry of

the company, or physical paper stock certificates. Instead, they hold

shares in "street name," meaning that their banks or brokers own the

shares on their behalf. This makes a lot of things more

convenient, especially if you want to sell your shares: You don't have

to contact the company and tell it to update its shareholder records,[3]

or mail stock certificates anywhere. Your broker, who actually owns

the shares, can handle it for you. But this means that your broker

also has to handle voting for you: The broker is the legal owner, so

it gets to vote, but it will ask you for instructions and then vote

however you tell it to.[4]

(Incidentally, this means that, if you are a shareholder in street

name and you want to show up and vote at the actual meeting, you have

to get a proxy from your broker so that you can get in.[5])

But usually it is more complicated than

that. Even the brokers mostly don't own the shares they hold for

customers in "street name." Instead, they've all agreed to put their

shares in one place, called the Depository Trust Co., which owns all

their shares for them.[6]

This makes transfers even more convenient; instead of moving around

physical share certificates between brokerages, everyone can just move

around entries in DTC's central computer. It does make voting one

level more complicated: Delightfully, DTC (or, strictly, its nominee,

Cede & Co.) is the record owner for state law purposes, while the

brokers are the record owners for federal law purposes, with the odd

result that Cede (the Delaware owner) has to give proxies to the

brokers (the federal owners) so that they can vote. By proxy. On

behalf of their customers.

But usually it is more complicated than that. Most

shares

are held, not by individuals, but by institutions, pensions, asset

managers, mutual funds, etc. Many of those institutions own shares in

hundreds or thousands of companies, and can't keep track of all those

companies' meetings. So often they hire someone to keep track of the

meetings, submit their proxies, and generally be in charge of voting.

The situation is similarly challenging for brokers, who have to keep

track of even more meetings, and who similarly outsource their voting

obligations. So T. Rowe Price is a gigantic institutional asset

manager, and State Street is the broker for some of its funds, and

both of them outsource the voting stuff, to two different companies:

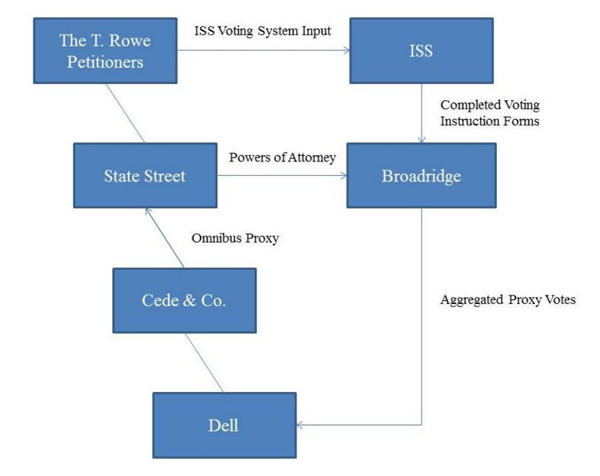

|

State Street outsourced to

Broadridge Financial Solutions, Inc. the task of collecting and

implementing voting instructions from its many account holders,

including the T. Rowe Petitioners. To carry out that task, State

Street gave Broadridge a power of attorney which authorized

Broadridge to execute proxies on State Street’s behalf. At that

point, voting authority for the T. Rowe Petitioners’ shares rested

with Broadridge.

To fulfill its contractual

obligations to State Street, Broadridge communicated with State

Street’s account holders and obtained voting instructions by mail,

by telephone, or over the internet. With T. Rowe, the process

involved an additional party: Institutional Shareholder Services

Inc. (“ISS”). To facilitate the submission of voting instructions

in connection with numerous meetings of stockholders each year, T.

Rowe has retained ISS to notify T. Rowe about upcoming votes,

provide voting recommendations, collect T. Rowe’s voting

instructions, and convey them to Broadridge. To make the voting

process more efficient, T. Rowe has a computerized system

that automatically generates default voting instructions and

provides them to ISS. |

That's from Wednesday's

Delaware Chancery Court decision

about the 2013 leveraged buyout of Dell Inc., which features this

lovely chart of how those shares were voted:

It isn't as simple as just showing up to

a shareholder meeting when you're invited! There are wheels within

wheels within powers of attorney.

One reason that I have told you this

boring complicated story is to persuade you that it is boring and

complicated. In human life, things that are boring and

complicated tend to get messed up, because honestly, who wants to pay

attention to all this stuff?

As it happens, T. Rowe Price's votes

on the Dell buyout got messed up in two completely separate ways,

requiring two separate Delaware court opinions. T. Rowe Price opposed

the buyout, which was led by Michael Dell, the company's founder and

chief executive officer. Several T. Rowe Price funds not only vocally

opposed the deal, they also demanded appraisal of their shares, which

is the process by which a Delaware court determines how much the

shares were worth and orders the surviving company to pay the

difference. The buyout price for Dell ended up being $13.88 a share.

T. Rowe thought it should have been more, so it sued.

It lost. Twice. On technicalities. The

Delaware appraisal statute[7]

has pretty strict rules, two of which are that, to get appraisal:

1.

You have to demand appraisal in writing before the merger closes, and

hold your shares continuously until the closing, and

2.

You have to vote against the merger.

All of the relevant T. Rowe Price funds more or less did both

of these things. But not quite! Last year some of the funds' appraisal

lawsuits were dismissed because they flunked the first test, for

reasons that were

entirely ridiculous:

At some point, the shares beneficially owned by some T. Rowe funds had

their official record ownership transferred from Cede & Co. to Kane &

Co., a nominee of JPMorgan, which was the custody broker for those

funds. The T. Rowe funds never sold those shares, but their entirely

arbitrary legal ownership changed, which was enough to disqualify them

from appraisal.

But the T. Rowe funds custodied with

State Street avoided this problem, and stayed at Cede & Co. the whole

time. They had an even dumber problem: They voted in favor of the

deal. They didn't mean to, but they did, just because, you know, this

stuff is so boring and complicated, who can keep track? The Dell

buyout was so controversial that the shareholder meeting had to be

rescheduled several times to get enough votes (and negotiate a higher

price). Before the first scheduled meeting, ISS asked T. Rowe Price

how it wanted to vote, and T. Rowe told ISS that some of its funds

wanted to vote against the merger. So ISS recorded the votes against

the merger. The first couple of times the meeting was postponed,

nothing happened: ISS just kept the old voting instructions from T.

Rowe, and T. Rowe logged back into the ISS voting system anyway to

make sure the instructions were correct. Everything worked smoothly

and redundantly. But then:

|

On September 4, 2013, the ISS Voting

System generated a new meeting record for the re-scheduled meeting

(the “September Meeting Record”). The T. Rowe Voting System showed

both the July Meeting Record and the September Meeting Record. In

the ISS Voting System, however, the September Meeting Record

replaced the July Meeting Record. This had the effect of deleting

the voting instructions that had been entered in the ISS Voting

System.

The T. Rowe Voting System

automatically pre-populated the September Meeting Record with the

default voting instructions called for by T. Rowe’s voting

policies. As a result, the T. Rowe Voting System populated the

September Meeting Record with instructions to vote “FOR” the

Merger, “AGAINST” the advisory resolution on golden parachutes,

and “FOR” authority to adjourn the meeting.

No one from T. Rowe’s proxy team

logged into the ISS Proxy System to check the status of T. Rowe’s

voting instructions. As part of the routine operation of the two

systems, the default instructions in the September Meeting Record

were conveyed automatically to ISS. |

Oops! I don't know whose fault this was.

ISS's computer probably shouldn't have overwritten the old

instructions. The T. Rowe proxy team probably should have

double-checked that its instructions were right, like, the day before

the vote. But it isn't hard to be sympathetic to both sides. The

surprise is that this doesn't happen all the time.

By the way, you might assume that, since the law requires you to vote

against the deal to get appraisal, and since T. Rowe Price voted in

favor of the Dell deal, its appraisal lawsuit would be an obvious

no-hoper and get tossed pretty quickly, but: nope. It took years, and

the

decision dismissing it

is 70 pages long. This is in part because Vice Chancellor J. Travis

Laster takes even more delight than I do in going through all of the

complexities of the voting system, but also in part because T. Rowe

had a real -- and paradoxical -- argument that it could demand

appraisal, because it didn't own the shares, Cede did,

and Cede voted enough shares against the deal to preserve its

appraisal rights. The court didn't buy it -- I don't either -- but it

wasn't a terrible argument.[8]

When we talked about last year's T. Rowe-Dell decision,

I

said:

|

The financial system is built up

in layers of abstraction over some vast and unwieldy machinery.

The machinery is complicated in part in order to make the

abstraction simple: You can buy stock with a click of a

mouse because armies of people devote their careers to the legal

niceties and operational maintenance and integration of all this

back-office apparatus. |

And sometimes they forget to check their

voting instructions for the fourth time, and mild disaster ensues.

The obvious question is: Does it have to

be this way? The machinery is complicated in part to make the

abstraction simple, but also because it has accreted over decades to

respond to particular problems in more or less ad-hoc ways, and

because decisions made to simplify one thing, like stock transfers,

have complicated other things, like voting. But computers are better

now than they were when DTC was invented, or for that matter when

proxy cards were invented. You could just, you know, build a big

database of who owns shares, and transfer shares on that database, and

not rely on a system in which people own shares in brokers' databases

and brokers own shares in DTC's database and DTC owns shares in

companies' (transfer agents') databases. The big database could send

out voting instructions directly to the shareholders, cutting back on

the outsourcing. You could build a new system, from the ground

up, corresponding to the actual practices of finance rather than to

the archaisms that they're built on.

This is of course more or less

the dream of the blockchain,

though there it is overlaid with a lot of mysticism about

decentralization and cryptography. The mysticism can occasionally be

annoying, but it serves an obvious function. All of this stuff is so

boring. The people in charge of building the systems that transmit

the voting instructions from the brokers' voting agents to the mutual

funds' voting agents -- those people are not celebrities. Those people

don't give keynote speeches at conferences. The blockchain's key

benefit,

I

tend to think,

is sociological: It makes this sort of back-end database technology

stuff cool. A little overenthusiastic hand-waving may be a small price

to pay to get people to pay attention to systems.

At the same time, though, technology is

mostly good for solving technological problems. Building a really good

computer system to keep track of share ownership is a good idea, but

it isn't the hard part. (Building one simple system should be easier than

the complex accretion of systems we have today.) The hard parts are

sociological -- getting actors in the current system to give

up control, and perhaps their market niches, to cooperate in building

a new system -- and also, perhaps above all, legal. Laws exist,

and many of them were written decades ago and are not well adapted to

the conveniences of modern technology.

Earlier this week,

I

wrote about

LendingClub's recent legal troubles, in which its push to simplify and

disintermediate lending may have led it to cut some legal corners with

the loans it was selling to customers. But I didn't want to put too

much blame on the "financial technology" mindset. I said: "The fintech

industry, after all, didn't invent fintech." Securitization, the MERS

mortgage registry: These were attempts to transcend the old-timey

legal structures of lending and to create abstract,

technology-enabled, fast and convenient systems for trading and owning

loans. They mostly worked! But there were glitches, because the clever

new systems were built on top of inconvenient old rules. And just

because your new system is cleverer and faster, that doesn't mean you

get to ignore the old rules.

The DTC/Cede/street name/etc. system is

another case of pre-fintech fintech, a privately coordinated system

for simplifying and electronifying the cumbersome traditional

processes of owning and trading and voting shares. It's just that the

way to simplify those processes often made them more complicated in

other ways. Perhaps the next round of financial technology will avoid

that difficulty. But complexity is a stubborn survivor; often, when

you think you are getting rid of complexity, you are only moving it

somewhere else.

1.

I mean, in the normal merger case, it's

someone (or someones) who work for the company. In proxy fights, like

where a hedge fund is running its own nominees for the board, the

hedge fund can solicit shareholders to sign its own proxy card, giving

voting authority to someone who works for the hedge fund.

The Securities and Exchange Commission's proxy rules are set out in

Rule 14a-4.

The Delaware General Corporate Law proxy rules are in DGCL

section 212.

This post will eventually be about Dell, so I refer you to

the proxy statement

for Dell's 2013 buyout. The proxy card is at the very end; it says:

|

|

|

You hereby (a) acknowledge receipt of the proxy statement related

to the above-referenced meeting, (b) appoint Lawrence P. Tu and

Janet B. Wright, and each of them, as proxies, with full power of

substitution, and authorize them to vote all shares of Dell Inc.

common stock that you would be entitled to vote if personally

present at such meeting and at any postponement or adjournment

thereof and (c) revoke any proxies previously given.

This proxy will be voted as specified by you. If no choice is

specified, the proxy will be voted according to the Board of

Director recommendations indicated on the reverse side, and

according to the discretion of the proxy holders for any other

matters that may properly come before the meeting or any

postponement or adjournment thereof. |

|

On the back, there are some check boxes to vote For, Against, or

Abstain on the merger and a couple of other matters.

2.

Also phone and Internet voting

instructions, because who sends snail mail?

3.

By the way, it's usually more complicated

than that, too: Most companies have outside transfer agents to

keep track of their shareholder records. From

Wednesday's Dell decision:

|

|

|

Dell outsourced the obligation to maintain its stock ledger and

generate a stock list to its transfer agent, American Stock

Transfer & Trust Company, LLC (“American”). |

|

4.

This is in Rules 14b-1

and

14b-2.

5.

See, e.g., page 136 of

the

Dell proxy statement:

|

|

|

Stockholders of record will be able to vote in person at the

special meeting. If you are not a stockholder of record, but

instead hold your shares in “street name” through a bank, broker

or other nominee, you must provide a proxy executed in your favor

from your bank, broker or other nominee in order to be able to

vote in person at the special meeting. |

|

6.

Most of them. In the Dell

case,

the proxy says

that there were 1,755,951,717 shares outstanding as of the record

date. Wednesday's

Chancery decision

says that Cede & Co. was the record holder of 1,535,558,891 of them,

or about 87 percent.

7.

Section 262

of the DGCL, famous from the fact that it has to be

included in merger proxy statements.

8.

There were previous cases in which

appraisal-arbitrage investors bought shares after the record date for

voting on the merger (which is usually

weeks before the meeting date). So they didn't get to vote, and

companies argued that they shouldn't get appraisal because they

couldn't prove that the shares they bought had been voted against the

deal. The courts decided that this was unfair, and since Cede actually

owned all the shares anyway, the appraisal arbs could count Cede's

votes against the deal. That is, as long as Cede voted enough shares

against the deal to "cover" all the people seeking appraisal, the

arbitrageurs could assume that all the shares they bought were shares

that voted no, in the absence of evidence the other way.

That was rough justice, but again: in the absence of evidence the

other way. Here, we know that the T. Rowe funds actually voted for the

deal, so there is not much of a fairness argument for pretending that

they'd voted against. From the decision:

|

|

|

The evidence showing how Cede voted particular blocks of shares

provides a basis for distinguishing the Appraisal Arbitrage

Decisions. Under those opinions, an appraisal petitioner that held

in street name can establish a prima facie case that the Dissenter

Requirement was met by showing that there were sufficient shares

at Cede that were not voted in favor of the merger to cover the

appraisal class. This showing satisfies the petitioner’s initial

burden and enables the case to proceed. If there is no other

evidence, then as in the Appraisal Arbitrage Decisions, the prima

facie showing is dispositive.

The analysis, however, need not stop there. Once the appraisal

petitioner has made out a prima facie case, the burden shifts to

the corporation to show that Cede actually voted the shares for

which the petitioner seeks appraisal in favor of the merger. |

|

And since we can trace how T. Rowe/State Street/Broadridge/Cede/etc.

voted these shares, and since they voted for the merger, they lose.

Incidentally, record dates -- where you have to own the shares weeks

before the meeting to vote the shares at that meeting -- are kind of

another weird archaism.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial

board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Matt Levine at

mlevine51@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Greiff at

jgreiff@bloomberg.net

©2016 Bloomberg L.P. All Rights Reserved |