|

THE WALL STREET

JOURNAL. |

Business

|

Business

Activist

Investors Often Leak Their Plans to a Favored Few

Strategically Placed

Tips Help Build Alliances for Campaigns at Target Companies

|

|

By

Susan Pulliam, Juliet Chung,

David Benoit and Rob

Barry

March 26, 2014 10:37

p.m. ET

Shares of

Rino International Corp. sank

28% in the two days after investment firm Muddy Waters LLC put out a

report attacking the Chinese company's accounting.

Three investment firms were ready for the news.

|

|

|

For a new breed of

"activist" investors, tipping other investors is part of the

playbook. Susan Pulliam joins MoneyBeat with details. Photo:

Bloomberg News. |

|

The firms had been tipped beforehand by Muddy Waters about the

scathing November 2010 report, according to a person close to the

matter, who said one of them made a bet against Rino stock that

produced a $1 million-plus profit.

"We sold advance copies of our report," said Muddy Waters's founder,

Carson Block, adding that since then he has tried to limit advance

knowledge of his firm's research.

For a new breed of "activist" investors, tipping other investors is

part of the playbook. Activists, who push for broad changes at

companies or try to move prices with their arguments, sometimes

provide word of their campaigns to a favored few fellow investors days

or weeks before they announce a big trade, which typically jolts the

stock higher or lower.

In doing so, they build alliances for their planned campaigns at the

target companies. Those tipped—now able to position their portfolios

for price moves that often follow activist investors'

disclosures—benefit in a way that ordinary stockholders who are still

in the dark don't.

"Premarketing, that's what they are doing. This is all part of the

campaign. They are building a constituency," said James Woolery,

chairman-elect of corporate law firm Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP,

who represents companies against activists. "Some are using, in

effect, the pop in the stock price to help pay these people" for being

on their side in a coming battle against the target company.

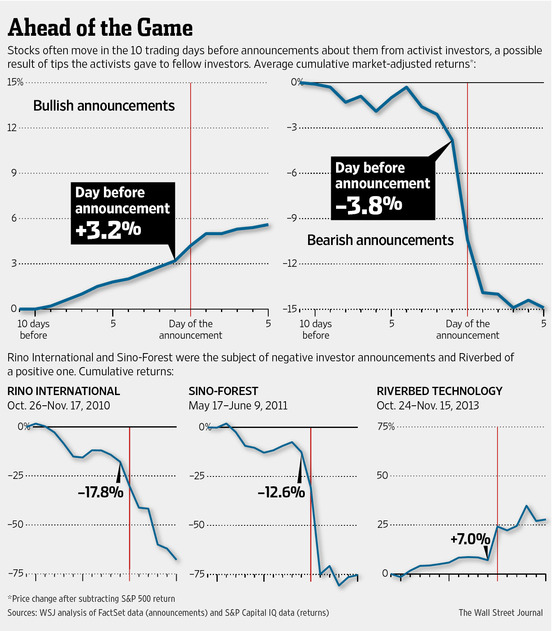

Stocks often move in the days just before activist investors tell the

world what they are up to, a Wall Street Journal investigation shows.

In the 10 trading days before bullish activists revealed in regulatory

filings that they had bought particular stocks, the stocks rose an

average of 3.2% more than the overall market, according to a Journal

analysis of 975 announcements by leading activist investors since

2007.

Similarly, an analysis of 43 announcements by bearish activists since

2007 found that in the preceding 10 trading days, shares of targeted

companies fell by an average of 3.8% more than the market as a whole.

It is impossible to know how much of the price change is due to

activists' own trading or other factors.

Many lawyers believe that there are few insider-trading risks in one

investor tipping another about his plans or actions because this

typically doesn't involve a breach of a duty to keep the information

confidential. A spokesman for the Securities and Exchange Commission

said he couldn't recall the agency having brought a case in the area.

But potential legal issues lurk. The SEC requires disclosure in

certain instances where investors act together on a particular stock.

And the agency recently has been expanding boundaries in its pursuit

of securities-fraud cases, some lawyers say.

At first glance, it might seem bizarre for an investment firm to tip

others to its intentions. Many large investors do the

opposite—striving to hide their moves, through techniques such as

breaking up large stock purchases into many tiny ones.

But activists approach stocks differently from investors who simply

take a stock position and wait for the market to justify it.

Activists—some of whom might have been called corporate raiders in the

past—don't just wait but try to move the stock by disclosing their

investment and often making a vigorous public argument about the

target company, pro or con.

The role they play can be positive. Bullish activists often pressure

management for changes some shareholders welcome, such as repurchasing

shares, raising dividends, spinning off noncore business units or

selling the company. Bearish activists can expose questionable

accounting or other issues. On the downside, companies' adoption of

short-term strategies to avoid being targets can have "very serious

adverse effects" on companies, attorney Martin Lipton of Wachtell,

Lipton, Rosen & Katz LLP has written.

Activist investors' clout is growing. They managed $93.1 billion last

year, up 42% from 2012, according to a tally by research firm HFR that

looked at 67 activist hedge funds.

Some activist investors say that speaking with other investors about

their ideas helps them test and refine their investment theses. "I'm

happy to give people my thoughts on things I own and I'm happy to

learn about how other people think," said Greg Taxin, who heads the

activist strategy of hedge-fund firm Clinton Group Inc. "Putting

earplugs in and blinders on isn't the smart approach." He said Clinton

pursues only "conversations that are permissible under the rules."

There also is a kind of buddy system among activist investors, some

say. Many high-profile investors who know each other don't want either

to get blindsided by another's investing—or to blindside others.

Lawyers often advise clients it is generally permissible to share

information about their trades before announcing them. "In the U.S.,

information that an investor would have about its intentions is not

material nonpublic information that can't be used," said David

Rosewater, a lawyer who represents a number of activist investors.

Still, there are gray areas that haven't been tested. Investors whose

stake in a company reaches 5%—a level SEC rules require them to

disclose—must inform the SEC if they are working as a part of an

investor group or have an understanding or agreement with other

investors about a stock. If one or more investors collectively own 5%

of a stock and are operating as a group, they too are required to

disclose that to the SEC, along with their holdings. Such disclosure

rules don't apply to bearish bets.

In recent months, the SEC has increased its focus on activist

investors' moves, including whether there is proper disclosure, a

person close to the situation said. Last summer it began looking into

whether some hedge funds were working together to try to profit ahead

of public disclosure of an investment stake.

The probe relates to the tug of war over nutrition company

Herbalife Ltd., which

William Ackman of Pershing

Square Capital Management LP has bet against and publicly criticized.

Last July 31, Herbalife's stock rose sharply after reports that Soros

Fund Management LLC had taken the opposite bet with a large stake in

Herbalife.

A couple of days later, according to a person familiar with the

situation, Mr. Ackman's lawyers wrote to the SEC alleging that a Soros

portfolio manager, Paul Sohn, had told people at other hedge funds

that the Soros firm would soon disclose a 4.9% Herbalife interest, and

had urged them to make the same bullish bet. On Aug. 14, the Soros

firm disclosed the 4.9% stake.

In a previously unreported development, the SEC has since sent about

25 subpoenas to hedge funds asking for information about their trading

in Herbalife, according to people familiar with the investigation. The

SEC spokesman declined to comment. So did a spokesman for Soros Fund

Management, which manages the assets of billionaire

George Soros, his family and

their foundations. Mr. Sohn didn't return calls for comment.

Some leaks occur even when activist investors say they have kept their

intentions quiet.

|

Pershing Square's

William Ackman Reuters |

|

On Nov. 8,

Riverbed Technology Inc. shares

leapt 16% after hedge-fund firm Elliott Management Corp. publicly

disclosed that it held a stake in the company. Before Elliott's

disclosure, information leaked to traders who acted on it by taking a

bullish position on the stock, according to a person who was apprised

of Elliott's intentions by a firm with close ties to Elliott.

In the 10 trading days before Elliott's disclosure, Riverbed shares

rose 7%. Elliott continued buying Riverbed shares during the 10 days,

a regulatory filing showed.

Elliott sometimes buys a stake, usually 5% to 10%, in a company and

then pushes for a sale of the whole company. Before such moves,

Elliott at times speaks with officials of private-equity firms about

their thoughts on the target company, people close to Elliott said.

Sometimes, Elliott has been on the receiving end of a tip.

Jana Partners LLC, another activist hedge fund, told Jesse Cohn,

Elliott's head of U.S. activist investing, that Jana had taken a stake

in

Juniper Networks Inc. before

news outlets reported this stake on Jan. 23, according to people

familiar with the matter.

Though Jana's investors had already been informed of the stake, and

Juniper stock was rising, the stock gained 1.2% more in after-hours

trading following the news reports. Elliott, which was already a

Juniper stockholder, didn't increase its Juniper position after the

tip from Jana, according to a regulatory filing.

Jana disclosed a 2.7% holding in Juniper in a regulatory filing on

Feb. 14. A Jana representative said there is nothing wrong with fellow

shareholders talking, adding that the fund firm already had told its

investors in advance of what he described as the "alleged

conversation" with Elliott's Mr. Cohn.

Critical research reports that Muddy Waters publishes on stocks often

knock them for a loop.

The targeted stocks, however, typically don't wait for the reports to

begin their slide. Twelve companies Muddy Waters has targeted since it

began publishing reports in 2010 tumbled an average of 13.1% below the

overall stock market in the 10 trading days before its reports came

out or the firm's Mr. Block publicly said he had bet against the

stocks.

Among such target companies was Rino International, which sank nearly

18% in the 10 trading days before a Nov. 10, 2010, Muddy Waters report

on it.

Before that report on Rino—a Chinese maker of equipment for the steel

industry—three investment firms, including hedge fund Oasis Management

LLC, paid $20,000 to $25,000 apiece for an advance look at the report,

a person familiar with the matter said. Oasis then placed a bet

against Rino's shares, the person said.

When Muddy Waters's report came out, it alleged that Rino showed

"clear signs of cooked books." Soon after, Rino disclosed a letter

from its auditor acknowledging some of the accounting problems raised.

Oasis closed out its bearish bet with a profit of more than $1

million, the person familiar with the events said.

In a statement, Oasis said it "purchases and subscribes to research

reports, analysis, and opinions from investment banks and independent

research firms," and follows "rigorous compliance procedures at all

times."

Two and a half years after Muddy Waters's report, the SEC alleged in a

civil complaint that Rino and two of its executives had inflated

revenue—allegations they settled without admitting or denying them. A

lawyer for Rino declined to comment. A lawyer for the executives said

they settled "to put the matter behind them." Rino's stock was

delisted. It recently traded over the counter at two cents a share.

In another case, Muddy Waters received an idea for a report from a

hedge fund and later asked questions that indicated a report could be

on the way, the person close to the situation said.

A senior person at Tiger Global Management LLC called Muddy Waters's

Mr. Block in 2011 to congratulate him on an investment success,

according to the person, and during the call said he wanted to "talk

at" Mr. Block about a Chinese company called Sino-Forest Corp.

The Tiger Global person advised Mr. Block not to respond, saying that

any response could make it impossible for Tiger Global to trade

Sino-Forest stock because of regulatory compliance issues, the person

added.

|

Soros Fund's George

Soros Bloomberg News |

Some time later, Mr. Block called Tiger Global asking detailed

questions about Sino-Forest, which showed he had researched it deeply,

the person said. Soon after, Muddy Waters issued a report on

Sino-Forest labeling it a "fraud." Sino-Forest denied the allegation

and filed a defamation suit against Muddy Waters and Mr. Block, which

Mr. Block said at the time was "without merit." The suit is pending.

In the 10 trading days before Muddy Waters made its negative report

public, Sino-Forest's share price sank 12.6%. When the report

appeared, the stock fell a further 21%, then 64% more the day after

that.

Mr. Block, speaking generally and not about Tiger Global, said, "It's

a balancing act for us, because we want to do research as thoroughly

as possible without tipping someone off to what we are working on."

Tiger Global declined to comment.

John Courtade, a lawyer for Muddy Waters who is a former assistant

chief litigation counsel at the SEC, said, "There's nothing

questionable about investors doing their own due diligence, writing a

report, or choosing to speak about some aspect of their work with

other investors."

Sino-Forest faces a regulatory hearing this fall on fraud allegations

by Canadian authorities alleging it inflated assets and revenue. Since

the Muddy Waters report, Sino-Forest has gone through a court-ordered

restructuring and now is a private entity. A lawyer for Sino-Forest

declined to comment on the allegations.

After the report, Mr. Block called Tiger Global to thank the manager

who provided the initial tip, the person familiar with the situation

said, adding that the Tiger Global manager cut him off and refused to

acknowledge the earlier conversation.

Write to

Susan Pulliam at

susan.pulliam@wsj.com, Juliet Chung at

juliet.chung@wsj.com, David Benoit at

david.benoit@wsj.com and Rob Barry at

rob.barry@wsj.com

U.S. News

Methodology: Analyzing Stock Moves Before Activist Investor Events

March 26,

2014 10:37 p.m. ET

To analyze price moves before investor announcements, The Wall Street

Journal obtained a list from FactSet showing about 1,100 SEC filings

by 50 top activist investors disclosing their positions between 2007

and early 2014.

Removing companies with multiple announcements within a 30-day period,

plus a handful of cases where stock prices weren't available for a

full 10 trading days before announcements, left 975 activist events.

Reporters calculated the price change from market close 11 trading

days before the announcement to market close one trading day before

the announcement. To adjust for the market, reporters subtracted the

S&P 500's change over the same period.

Because investors aren't required to disclose short positions,

reporters manually compiled a list of 43 high-profile announcements by

bearish investors since 2007, and performed the same calculation.

The results showed that targeted companies' stock price increased by

an average of 3.2% above the market in the days before bullish

announcements and decreased by an average of 3.8% below the market

before bearish announcements.

|