Wall Street

Bill Ackman Will Hold a Pretend Allergan Shareholder Meeting

May 12, 2014 2:19 PM EDT

By Matt Levine

Valeant's and Pershing Square's team bid for Allergan Inc., with a bidder and an activist working together to build a toehold to support a hostile takeover, is turning into sort of a weird textbook for The Future of Mergers & Acquisitions. But one longstanding, obvious textbook lesson is that, if you're a board, and someone makes a hostile bid for your company, you say no. Today Allergan said no:

It is the unanimous view of the Allergan Board of Directors that Valeant’s unsolicited proposal substantially undervalues Allergan, creates significant risks and uncertainties for the stockholders of Allergan, and is not in the best interests of the Company and its stockholders

And perhaps it isn't. But, again, they'd say that no matter what. If you think that a takeover is not in the best interests of stockholders, you say no.1 If you think it is, and you want to do a deal, you still say no: The best way to negotiate a higher price is by playing hard to get. "Interesting, but we want a higher price" does not give you much negotiating leverage; once you admit you're willing to be bought it's hard to walk away over price. The trick is to say no consistently until the moment you sign the merger agreement.2

Valeant and Pershing Square, of course, know that trick, so they'd rather have Allergan come to the table, and as publicly as possible. But there's no particular reason for Allergan's board to listen to Valeant, and there's not all that much reason to listen to Pershing Square, despite its 9.7 percent ownership. On the other hand, other, longer-term shareholders -- the holders list starts with Capital Group and BlackRock, and includes T. Rowe Price, AllianceBernstein and Oppenheimer -- might have Allergan's ear. And they have good reason to want Allergan to negotiate. Particularly this reason:

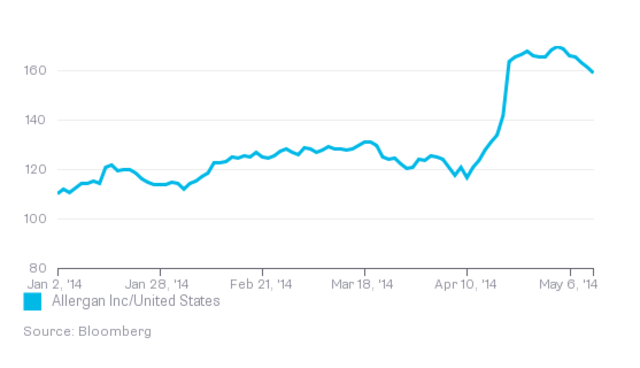

Allergan's shareholders are around $12 billion richer than they were before Valeant's offer.3 Sending Valeant packing would, presumably, lose them that value; even Allergan's rejection of the bid today -- which is not so much "sending Valeant packing" as it is "doing the textbook obvious thing" -- had the stock down this morning.

So you'd expect some amount of lobbying from shareholders here. But Valeant and Pershing Square have a cleverer plan than just hoping that shareholders pressure Allergan to sell. They're going to call a vote. Not a real vote, but a show vote:

In the interim, however, together with Pershing Square, we will be requesting a shareholder list from Allergan, which they are required to provide under Delaware law.4 We will then commence a shareholder referendum that will determine that the Allergan shareholders are supportive of Allergan’s board engaging in negotiations with us in parallel with other efforts they may be undertaking. We expect that this referendum will send a clear message to the Allergan board, and to us, that Allergan’s shareholders strongly support negotiations between our two companies, in parallel with their other efforts.

The plan seems to be for Pershing Square and Valeant to hold their own, rogue vote of Allergan shareholders, and ask those shareholders if they want Allergan to negotiate with Valeant. The answer they're hoping for is yes.

So how crafty is that? For one thing, it's a good way to organize and publicize shareholder pressure on Allergan to talk to Valeant. The way mergers normally work is that first the board decides whether or not to do a merger, and then puts it to a vote of the shareholders. If the board wants a deal and shareholders don't, then the shareholders can overrule the board; but if the board doesn't want a deal that shareholders want, the shareholders don't have much recourse.5

The referendum idea gets around that, sort of. Holding a vote -- even an informal nonbinding vote not sanctioned by the company -- lets shareholders express their preference. And if a majority of shareholders vote to hold discussions, in a public vote, it's harder for Allergan's board to keep rejecting discussions while saying that it's acting in the best interests of shareholders.

The referendum is also a way for Valeant and Bill Ackman to put their thumbs on the scales about what exactly Allergan's shareholders "say." If shareholders call Allergan privately, they'll have nuanced conversations about strategy and valuation and negotiating tactics.6 A yes-no referendum, run by Valeant and Pershing, can be lighter on nuance. The referendum "will determine whether shareholders are supportive of Allergan's Board engaging in discussions with Valeant in parallel with other efforts underway" -- which is a pretty low bar. If you're Valeant and Pershing, and you're holding your own homemade shareholder meeting, you send out a ballot that looks like this:

Should Allergan's board, in addition to doing everything else that it is or isn't doing to enhance shareholder value, occasionally return Valeant's phone calls in order just to hear, in a low-pressure, no-commitment way, what a great idea a merger would be?

__ Yes, can't hurt.

__ No, they should stick their heads in the sand and totally ignore this huge value-creation opportunity for no reason at all, the jerks.

The best way to get the answer you want is to write the question yourself. Suggestively.

There's another, weirder benefit to this approach. Allergan's poison pill, adopted last month, is designed to handicap Pershing's and Valeant's efforts to get shareholder support. The pill triggers if anyone becomes a beneficial owner of 10 percent or more of Allergan's stock; Pershing and Valeant are at 9.7 percent. But "beneficial owner" doesn't mean what it sounds like, or what it means in securities law. It includes any shares that Pershing and Valeant don't own, if they have any "agreement, arrangement or understanding to act together for the purpose of acquiring, holding, voting or disposing of any securities of the Company" with the holders of those shares.7

That makes it hard to communicate with other shareholders. It might, for instance, prevent Pershing from coordinating with other shareholders to call a special meeting (an actual binding shareholder vote) and vote out Allergan's directors. More generally, because the consequences of triggering a pill are so dire, it makes it scary for BlackRock or Capital Group to have any sort of conversations with Pershing and Valeant. If you meet with them, agree that their deal makes sense, and say that you'd support it, does that create an "agreement ... for the purpose of ... voting or disposing of" (by merger) your shares? Have you triggered the pill?

But the pill has an exception for consents given "in response to a public proxy or consent solicitation made pursuant to, and in accordance with, Section 14(a) of the Exchange Act by means of a solicitation statement filed on Schedule 14A": You can do a lot with a poison pill, but you can't just prohibit proxy fights; just voting for Valeant's proposals is allowed.

So what Valeant and Pershing can't do by means of private meetings -- get shareholders on their side -- they can do by way of public proxy solicitation. And since there's no actual proxy fight on the horizon -- Allergan just had its annual shareholder meeting last week and calling a special meeting would be difficult -- Valeant and Pershing apparently decided to make one up. Instead of calling up BlackRock and Capital and asking them to support the merger, they can send BlackRock and Capital "referendum" solicitations and then call them to urge them to vote. All they have to do is run the referendum as a proxy contest, and file their solicitations on Schedule 14A, which they are not shy about doing.

You can see the evolution of various strands of activism and M&A occurring here. It used to be that the poison pill blocked hostile takeovers by tender offer, while still allowing bidders to accumulate large stakes and coordinate for proxy fights. But the newer generation of poison pills, with lower thresholds and broad definitions of beneficial ownership, make it more difficult for bidders or activists to coordinate with shareholders to pressure boards. The referendum idea is a logical response, using loopholes in the new-style poison pill to allow shareholder coordination. If it works, there might be more of it, even in non-M&A activist fights. After all, activist hedge funds love proxy fights, and holding your own shareholder meetings means you can have a proxy fight pretty much whenever you want.

1 If you think it is, but you want to reject it for

reasons of job security and self-aggrandizement, you say no.

This is not, like, a super-interesting motive to ascribe to

Allergan's board, but obviously some people will ascribe it

anyway.

2 See, e.g., Jos. A. Bank, where just saying no seems to have worked.

3 Math on that is 307.6 million shares outstanding, minus Ackman's 28.9 million shares, times the difference between today's price ($159 as of around noon) and the $116.63 price before Ackman's "rapid accumulation." Some of those measures are debatable.

4 That happened today; here is Pershing Square's letter demanding a shareholder list "to enable the Requesting Stockholder to communicate with fellow stockholders of the Company on matters relating to their mutual interest as stockholders, such as those with respect to specific policies, actions, and affairs of the Company, including, without limitation, the solicitation of views regarding Valeant Pharmaceuticals International Inc.’s proposal to acquire the Company and the solicitation of proxies or written consents in connection with any election of the Requesting Stockholder’s nominees to the board of directors of the Company or any proposals submitted by the Requesting Stockholder for consideration at any annual or special meeting or in any action by written consent."

5 This is effectively the result of the poison pill. In the olden days, if shareholders wanted a deal and the board didn't, the bidder could just launch a tender offer, buy a majority of the shares, and then control the company. But the poison pill lets boards block hostile tender offers, meaning that in practice you need board approval for any deal.

6 Here is a conversation that could happen:

Shareholder: You should talk to Valeant.

Allergan executive: I hear you, but we think that saying no gets us more leverage. If they want to raise their bid, they know where to find us.

Shareholder: Hmm, okay. Maybe I'll call them back and urge them to offer a higher price.

That conversation is obviated by a "shareholder referendum."

7 That's section 1.3.3 of the pill.

To contact the writer of this article: Matt Levine at mlevine51@bloomberg.net.

To contact the editor responsible for this article: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net.