|

THE WALL STREET

JOURNAL. |

MARKETS

|

Markets

Activist Funds

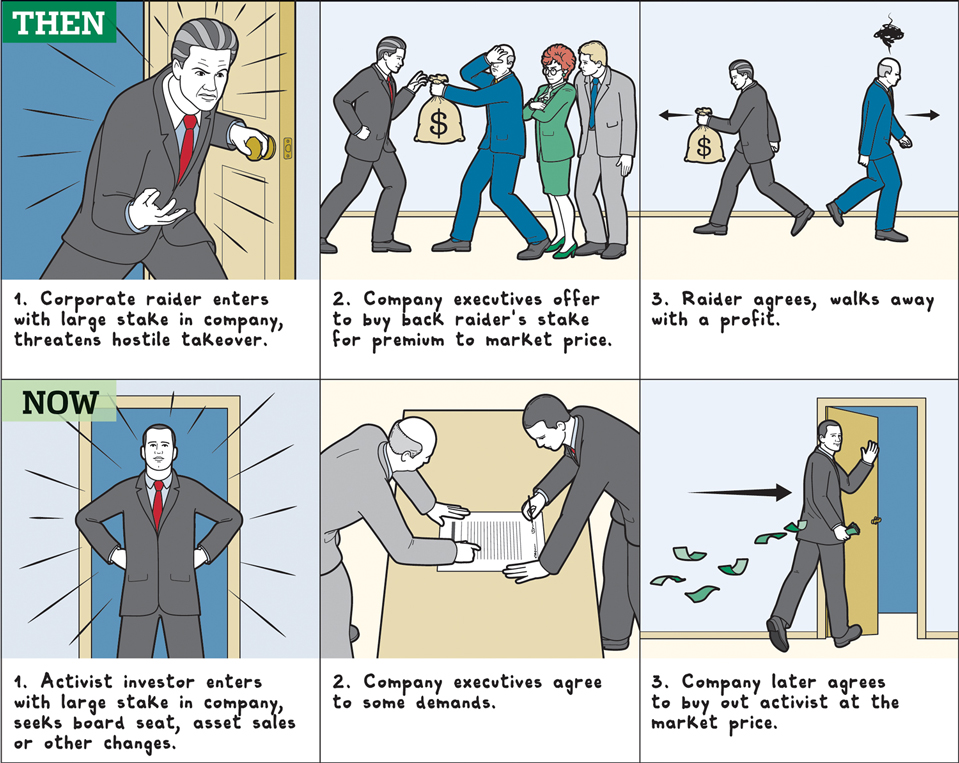

Dust Off 'Greenmail' Playbook

|

|

By

Liz Hoffman and David Benoit

June 11, 2014 7:03

p.m. ET

More

companies are resorting to an old tactic to get rid of activist

investors: Pay them to go away.

The

practice, which involves buying back shares from activist hedge funds,

has raised concerns among some investors because it bears similarities

to "greenmail," a controversial strategy popular in the 1980s.

Back

then, aggressive investors such as

Carl Icahn and the late Saul Steinberg bought company shares and

threatened a hostile takeover. Eager to avoid a battle, companies

including

Walt Disney Co. and

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.

bought back their stakes above market price, giving the activists a

quick profit.

The

practice, widely criticized as corporate blackmail, largely died out

by the early 1990s as companies beefed up defenses and lawmakers took

steps to discourage it.

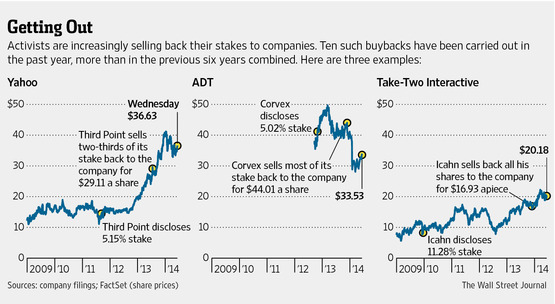

But

in the past 12 months, at least 10 companies have repurchased blocks

of shares from activist investors, including

Daniel Loeb and

William Ackman, according to FactSet SharkWatch. That is more than

in the previous six years combined.

The

practice differs from greenmail in two crucial aspects. The share

buybacks aren't at a premium to the market but typically at or

slightly below the last trading price. They also don't follow threats

of hostile takeovers.

Advisers say these deals are likely to continue as activist hedge

funds, which have targeted more companies in recent years, look to

sell out of holdings.

Since the current wave of activism started in 2010, these investors

have launched 1,115 campaigns, according to FactSet, and many are ripe

for exits.

The

buybacks have fueled a common criticism of activist investors: They

chase short-term profits at the expense of other shareholders.

"You

can call it greenish mail," said Spencer Klein, a lawyer with Morrison

& Foerster LLP who advises companies facing activist investors. "These

investors are getting an opportunity that others aren't, and that's

not a terribly popular notion."

The

trend is setting off alarms even among activists, who have sought to

separate themselves from the "corporate raiders" of the 1980s and

portray themselves as good for all investors.

"I'm

the curmudgeon in the room. I see evidence of greenmail," Jeffrey

Ubben, founder of activist fund ValueAct Capital Management LP, said

at a conference recently. "We better be careful we don't kill the

golden goose."

Defenders of these new deals say they offer a clean, amicable divorce.

Large stakes can drag down a company's stock price if sold on the open

market, and even the expectation of an exit in the near future can

weigh on shares. Both sides make out better when the split happens

quickly, said some activist investors and corporate advisers.

Buybacks also boost remaining investors' cut of future profits by

reducing the total number of shares in the market, they said.

Damien Park, a consultant who advises both corporations and activists,

said if the price makes sense for a company to do a large buyback, it

can be a win for everybody.

"One

of the most difficult aspects of being an activist is your exit

strategy," Mr. Park said. "Once the stock moves in the right direction

and things are going smoothly, you have a conundrum."

Still, the deals have drawn criticism. Home-security firm

ADT Corp. in November bought

back most of a 5.3% stake held by Corvex Management LP, a hedge fund

run by Keith Meister. ADT paid the previous session's closing price,

and Mr. Meister left the board.

ADT's stock has underperformed this year and, on an investor

conference call in April, anger from one large shareholder spilled

into the open.

"You

guys have bought back…stock at very inappropriate prices, as far as I

can see," said Leon Cooperman of Omega Advisors Inc. Mr. Cooperman

said in an interview that companies should be held accountable for

buybacks just as if they were spending on plants or acquisitions.

"Management owes the shareholders an explanation," he said.

Chief Executive Naren Gursahaney responded on the call that ADT had

worked with advisers and believed the price was a discount. "We feel

that the valuation is significantly higher than where it is," Mr.

Gursahaney told Mr. Cooperman. ADT declined to comment beyond the

CEO's earlier remarks.

ADT

shares closed Wednesday at $33.53, down 24% from the price Mr. Meister

received.

In

the past year, similar deals have been struck at or near market

prices, between Mr. Ackman and

General Growth Properties

Inc.; Mr. Loeb and

Yahoo Inc.; and Mr. Icahn and

two companies,

WebMD Health Corp. and

Take-Two Interactive Software

Inc.

Many

of the deals came amid broader share-repurchase programs. In each of

those examples, except ADT, the stock currently trades above the

buyback price.

Messrs. Meister, Loeb and Ackman declined to comment. Mr. Icahn didn't

respond to a request for comment. Yahoo, General Growth, WebMD and

Take-Two declined to comment.

In

its heyday, greenmail deals added up to big sums. In 1984 alone,

public companies paid $3.5 billion in greenmail, with payments above

market price accounting for $600 million, according to a study by the

Securities and Exchange Commission.

Then

the "poison pill" was invented. These corporate defense mechanisms,

officially called shareholder-rights plans, defanged activist

investors by thwarting the hostile takeovers they used as leverage to

extract the buyback offers.

Regulators also stepped in. The Internal Revenue Service in 1987

introduced a tax of 50% on any profits from greenmail, while several

states passed laws that made it hard for companies to buy back stakes

from short-term investors at a premium.

Write to Liz Hoffman

at

liz.hoffman@wsj.com and David Benoit at

david.benoit@wsj.com

|