Fortune Insider

Activist

Investors

Keeping activist

investors at bay: how corporate boards can help

|

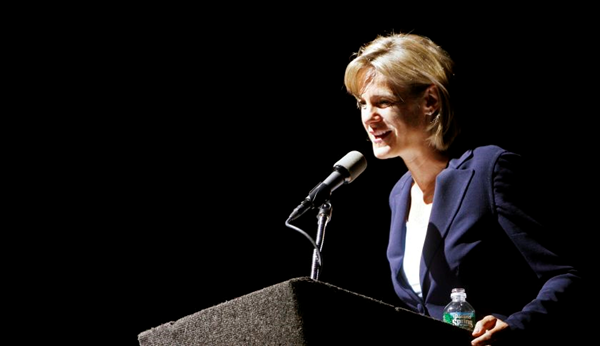

Susan Decker

Photograph by Brendan McDermid — Reuters

|

|

Sue Decker

Sue Decker serves on the boards of Berkshire Hathaway, Costco

and Intel. She previously served as president and chief

financial officer at Yahoo. |

|

Boards are empowered to protect

shareholders, but many have become sympathetic to activists because

they believe directors are subject to conflicts of interest.

The hottest topic in many corporate boardrooms today is

shareholder activism — or more specifically, the vulnerability of

becoming the target of a shareholder

activist and what to do about it. Instead of dreading this

or, worse, have to defend against it, boards of directors should be

proactive about getting out ahead of it. As insiders, we are in a

better position to act on our fiduciary responsibility to represent

the interests of shareholders than is an independent party, and we

have more tools and power at our disposal to do so. Done right, this

might result in some healthy, but managed changes.

The influence the activists are having in the market

has never been greater. Simply put, what they are doing is attracting

more interest and more capital, now estimated at north of $115

billion, 10 times the levels of the 1990’s. Distributing their

messages has also become easier. They often communicate via social

media and business news channels to emotionally pressure management

and collaborate with other shareholders.

So what is a board of directors to do? Boards are

empowered to protect shareholders, but many shareholders have become

sympathetic to activists because they believe the system has inherent

conflicts of interest; that directors are more interested in

collecting paychecks and preserving their status quo than in

exercising their fiduciary duty to shareholders.

Conversely, the board’s time horizon for creating value

is by definition much longer than that of any one activist, and many

boards and management teams feel activists are too short-term and just

don’t get the complexities of the landscape in which they operate.

Operating realities include balancing the interests of customers,

suppliers, employees, and regulators. Implementing well-managed

changes, while navigating these factors, often takes longer than

investors may realize.

But there are many things public company boards can do

to better align with their core responsibility to the stockholders—and

they can do it in a way that is proactive and more long-term in nature

than if it is in response to an activist.

Here are three ideas, which are meant to be directional

rather than prescriptive.

Let shareholders air it out.

Most boards only receive input from reading reports by

sell-side analysts, who are not their shareholders, and from the CEO

and CFO, who directly talk to institutional shareholders. Imagine, as

an executive, never meeting with your boss to get feedback, but

instead receiving it filtered from someone on your staff. That’s

essentially what happens for many boards.

The shareholders are ultimately the “boss” of the board

in the sense that the board serves as their proxy for enhancing

intrinsic value. Yet boards typically hear about shareholder concerns

indirectly and often not attributed to any specific shareholder.

A huge opportunity is missed without direct contact.

This is exactly the opportunity the activists are availing themselves

of by contacting blocks of shareholders to exchange views on

underperforming companies and collaborating on remedies.

Boards should do the same. There are a variety of ways

to accomplish this. For example, Coca-Cola Co. Director Maria Elena

Lagomasino, Chair of the Compensation Committee, met directly with one

large shareholder and also considered specific feedback derived from

major institutional shareholders of Coke (KO)

on the issue of executive compensation. This input led to

the revised approach to equity compensation, communicated by her

directly with shareholders through the company’s website.

This could even become part of a regular process. For

example, a designated board member could invite large shareholders to

periodic get togethers to air their thoughts and concerns. This

feedback could either be summarized for the board by that board member

or delivered directly by a representative from the group at a board

gathering.

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (BRK)

is even more ambitious. It hosts more than 30,000

shareholders in Omaha annually and allows them more than six hours to

ask unfiltered questions. Recently, Chairman and CEO

Warren Buffett offered some sage

advice on the subject. “I believe in running the company for

shareholders that are going to stay, rather than the ones that are

going to leave.”

If a designated director or a designated third party

representing the board were to reach out to shareholders from time to

time, both sides would learn and benefit. It would allow key directors

to educate shareholders, as well as build credibility and a

relationship before problems arise. In addition, shareholders can add

insight to the board, because they often speak with competitors,

customers, and suppliers of the company and can bring an “outside in”

perspective that can be hugely valuable.

Limit terms, but don’t install terms limits.

This means setting up a mechanism for both attracting

new directors with some of the skill sets of long-term shareholders,

as well as a mechanism for rotation off the board to create room for

new thinking, more diversity, and women.

For removing directors, the solution that activists

primarily advocate is a hard term-limit. As an alternative, many

companies instead opt for a retirement age. I am not a fan of either.

Why create a system that force out good board members?

Then again, most boards have at least one or maybe a

few directors who are not adding as much value as a new member might

bring and therefore represent an “opportunity cost.” Once directors

are on a board, it can be extremely difficult to naturally rotate them

off. Firing a friend is tough under the best conditions, and even more

so because there is no economic incentive.

It’s emotionally easier just to “wait it out.” This is

even more complicated when a CEO inherits a board that was picked and

groomed by her predecessor and doesn’t have the collective skills for

her new strategy.

My view is that boards would be well served to adopt a

process that specifically outlines the rotation process and that is

understood and implemented for new directors. In other words, limited

terms, but not unified term-limits. By making this change for all new

directors, it side-steps the issue of those already on the board,

making it easier to implement on a go forward basis.

I lean toward a system in which each new member of the

board agrees to hand in their resignation every six to eight years,

with the idea being that some directors will be asked to serve

multiple terms it they are uniquely qualified to help the CEO and

company build value, but many will be thanked for their service and

move on after that time frame.

The decision regarding whose resignations to keep, or

whose to accept, could be made either by an appointed director, or by

an absolutely confidential and binding majority vote of the other

board members. This latter approach might be easier socially.

Think like an activist.

Directors must insist on asking management to analyze

strategic choices as an activist would: by looking at alternatives to

the strategies the CEO is recommending. This is not typical. The more

common pattern is for the CEO to consider options and present only the

recommended one to the board.

The road not taken is the one the activist will surface

so the board must have analyzed these alternatives. This means

understanding what it would mean to get out of underperforming

operations, split up the company and evaluate varying alternatives for

measuring and handling excess cash versus the ones being recommended.

If these choices are not discussed, the board will be poorly prepared

to articulate and defend its alternative course.

Importantly, an analysis of the break-up or private

transaction value of a company that shows a higher value than where

the stock is trading does not oblige a company to make a sale. There

have been many times in history where macro-economic or other

conditions have made the current stock market and private transaction

values poor indicators of intrinsic value. The board’s duty is to

enhance the latter, exercising its duty of care, by fully

understanding what strategic choices the company is making and why.

By proactively using their power to align with

long-term shareholder value creation, boards can help companies avoid

the disruption that a shorter-term activist agenda will bring.

Sue Decker serves on the boards of Berkshire Hathaway, Costco and

Intel. She previously served as president and chief financial officer

at Yahoo. This article is an excerpt from a more detailed version

published on Sue’s blog,

deckposts.net. The opinions

expressed are her own and not necessarily those of the companies on

whose boards she serves or her colleagues on those boards.

|