|

THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

Markets

Companies Send More Cash Back to Shareholders

Activists

push for returns, fueling worries about long-term investment

|

Every proposed project at U.S. Steel, whose Granite City, Ill.,

plant is shown in March, must be linked to the value it could

create for shareholders. PHOTO: HUY MACH/ST. LOUIS

POST-DISPATCH/ASSOCIATED PRESS |

By

Vipal Monga,

David Benoit

and

Theo Francis

May 26, 2015 10:30 p.m. ET

U.S. businesses, feeling

heat from activist investors, are slashing long-term spending and

returning billions of dollars to shareholders, a fundamental shift in

the way they are deploying capital.

Data show a broad array of

companies have been plowing more cash into dividends and stock

buybacks, while spending less on investments such as new factories and

research and development.

Activist investors have

been pushing for such changes, but it isn’t just their target

companies that are shifting gears. More businesses sitting on large

piles of extra cash are deciding to satisfy investors by giving some

of it back. Rock-bottom interest rates have made it cheap to borrow to

buy back shares, which can boost a company’s stock price. And

technology-driven productivity gains are enabling some businesses to

do more with less.

As the trend picks up

steam, so too has debate about whether activist investors—who take

sizable stakes in companies, then agitate for changes they think will

boost share prices—have caused companies to tilt too far toward

short-term rewards.

Laurence Fink,

chief executive of

BlackRock Inc.,

the world’s largest money manager, argued

as much in a March 31 letter to S&P 500 CEOs. “More and more corporate

leaders have responded with actions that can deliver immediate returns

to shareholders, such as buybacks or dividend increases, while

underinvesting in innovation, skilled workforces or essential capital

expenditures necessary to sustain long-term growth.”

|

Photo: Sam Kang Li/Bloomberg News

‘While delivering immediate shareholder returns, executives are

‘underinvesting in innovation, skilled workforces or essential

capital expenditures necessary to sustain long-term growth.’

—Laurence Fink, CEO Blackrock Inc.

Photo: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg News

‘With many, many exceptions, this economy today is being dragged

down by too many mediocre CEOs.’

—Carl Icahn, activist investor

|

|

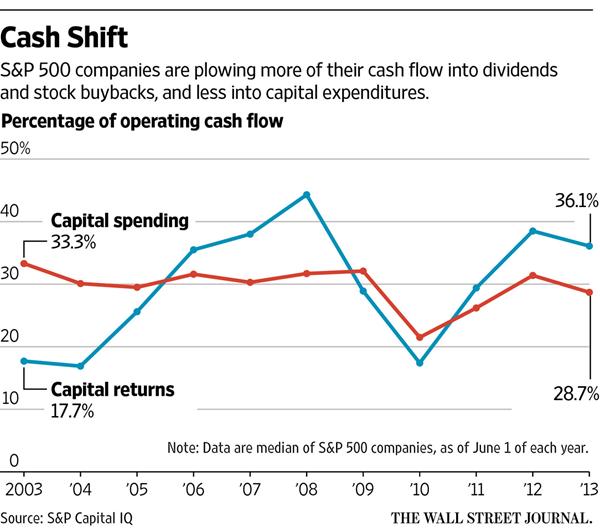

An analysis conducted for

The Wall Street Journal by S&P Capital IQ shows that companies in the

S&P 500 index sharply increased their spending on dividends and

buybacks to a median 36% of operating cash flow in 2013, from 18% in

2003. Over that same decade, those companies cut spending on plants

and equipment to 29% of operating cash flow, from 33% in 2003.

At S&P 500 companies

targeted by activists, the spending cuts were more dramatic. Targeted

companies reduced capital expenditures in the five years after

activists bought their shares to 29% of operating cash flow, from 42%

the year before, the Capital IQ analysis shows. Those companies

boosted spending on dividends and buybacks to 37% of operating cash

flow in the first year after being approached, from 22% in the year

before.

Dividend

boost

While billion-dollar stock buybacks draw

headlines, dividend increases also are a big factor, according to data

from

Moody’s Investors Service.

At the 400 nonfinancial U.S. companies

that Moody’s rates as investment grade, the median percentage of cash

spent on dividends rose to 11.9% of earnings before interest, taxes,

depreciation and amortization, or Ebitda, in the third quarter of last

year, from 9.4% in 2013, to the highest percentage since at least

2005.

Companies ranging from the industrial

conglomerate

DuPont Co.

to

Apple Inc.

are sending more of their cash to their

shareholders after coming under pressure from activists.

General Motors Co.

announced a $5 billion stock

buyback in March after investor Harry

Wilson and four hedge funds called on the company to return cash to

shareholders.

It is it too early to know

how—or whether—the shift will affect the overall economy.

Some economists predict an

investment reduction will mean less growth and fewer jobs. “If

investment falls, then you’re losing demand in the economy, you’re

losing expenditures, you’re losing economic stimulus,” says Steven

Fazzari, an economist at Washington University. “That’s hurting jobs.”

Other economists say it is

appropriate for companies to focus on enriching shareholders, who can

then decide where to deploy the money. To the extent buybacks and

higher dividends push up stock prices, they can contribute to what

economists call the wealth effect, where rising asset prices make

consumers feel wealthier and more confident about spending their

money.

Hedge funds run by

activist investors contend companies waste a lot of money that they

should send to shareholders instead. One such investor, Carl Icahn,

says activism with a long-term focus improves the economy by promoting

efficient use of capital. “With many, many exceptions, this economy

today is being dragged down by too many mediocre CEOs, and it’s

dangerous if profitability is going down despite interest rates being

at zero,” he says.

Business investment ticked

up in April but remains sluggish and uneven. In recent years,

corporate investment in capital goods, beyond replacing and

maintaining existing assets, has grown slowly. While falling

technology costs may account for some of the trend, companies have

been slow to return to higher investment levels since the financial

crisis. “One could argue that this has not been a good recovery for

investment,” says Christopher Probyn, chief economist for State Street

Global Advisors.

Capital spending by

businesses accounts for about one-eighth of all spending in the U.S.

economy. Historically, it has been an important driver of long-term

growth, as upgrades make workers and companies more productive, says

Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at

J.P. Morgan Chase

& Co.

Money plowed into

dividends and buybacks doesn’t disappear from the economy. Its

recipients can spend it, too.

But Washington

University’s Mr. Fazzari says that most stock is owned by the wealthy,

who tend to save more of their income. By contrast, he says, many

kinds of business investment—from building construction to equipment

maintenance and purchases—involve payments to contractors and

suppliers who pay wages to middle and low-income workers.

Many companies have made changes while

under no direct threat from activists.

General Electric Co.

’s institutional investors had long urged

the conglomerate to scale down its large lending business. In April,

GE said it would sell off that business

and buy back $50 billion of its stock.

The company said it chose

to plow the proceeds into buybacks because it already had made

substantial acquisitions and has invested sufficiently in its existing

businesses.

U.S. Steel

Corp. buying back stock. But Chief Executive Mario Longhi has imposed

a new analytical framework under which every proposed project must be

linked to the value it could create for shareholders. The more

disciplined approach sets a higher bar for R&D, which used to get a

green light if it could simply boost production, says Mr. Longhi.

U.S. Steel is under

pressure from cheaper imported steel and has a high cost structure

because its blast furnaces are expensive to turn on and off, says Mr.

Longhi. The need to keep the company lean and viable, he says, led to

the changes.

Keeping activists at bay,

he says, is a side benefit. “If an activist decides to look at our

company, I don’t think they’re going to find a lot of room,” he says.

Years of uncertain global

demand and revenue growth, combined with corporate-governance changes

that have made it easier for dissident shareholders to campaign for

board seats, have opened the door to investors with ideas for boosting

stock prices.

Activist

campaigns

The number of activist

campaigns annually has risen 60% since 2010. Last year there were 348,

the most since 2008, according to data provider FactSet. An additional

108 were launched in this year’s first quarter. Activist funds now

control nearly $130 billion in assets, more than double the amount

they had in 2011, according to hedge-fund tracker HFR, giving them the

war chests to target even the biggest American corporations.

Activists say they are

strengthening companies that tend to overspend and holding managers

responsible to their ultimate owners, the shareholders.

Network-equipment maker

Juniper Networks Inc.

came under pressure last year from

Elliott Management Corp., a New York-based hedge fund. The fund

criticized Juniper for spending $7 billion on acquisitions and nearly

$8 billion on R&D when its stock price had underperformed the Nasdaq

Composite Index by 63 percentage points between the company’s 1999

initial public offering and Nov. 4, 2013.

In February 2014, in an

agreement with Elliott that avoided a potential board fight, Juniper

appointed two new directors and

announced a plan to repurchase stock and cut

costs. The company reduced its head count by 7% and

repurchased $2.25 billion of stock last year. This year it appointed

two more directors after a joint search, and it plans to buy back

almost $2 billion more in stock through 2016. The company paid its

first-ever dividend last year. It has borrowed money to fund some of

the buybacks and dividends.

In early 2012, New York investment firm

Clinton Group Inc. took a stake in teen-fashion retailer

Wet Seal Inc.

and began urging a share buyback. In

February 2013, the company disclosed it was cutting jobs and expenses

and would repurchase $25 million of stock after appointing four

Clinton representatives to its board.

This January, Wet Seal

closed two-thirds of its stores and filed for bankruptcy protection.

In court documents, executives cited a broader drag on teen retailers

as well as missteps that alienated core customers.

Others contend the buyback

ultimately hurt the company. “If we had rewound and…they hadn’t done

the buyback, that would have given them substantially more

flexibility,” says Jeff Van Sinderen, an analyst at

B. Riley

& Co. “In those situations, $25 million

dollars can go a long way.”

The debate over R&D

spending flared up at chemicals maker DuPont amid pressure from

activist

Nelson Peltz and his Trian Fund

Management LP.

On May 13, DuPont

won a proxy fight for board seats,

in part by arguing that Trian’s suggestions to cut costs and break up

the company would get in the way of scientific breakthroughs, a

concern that struck a chord with some shareholders and academic

commentators. Trian had questioned whether DuPont’s current system of

R&D can be successful, but said it wouldn’t eliminate such spending

entirely.

Among other moves, DuPont

increased its quarterly dividend in April and has pledged to

repurchase about $4 billion in stock after a planned spinoff of its

performance-chemicals business.

The choice between

investments and shareholder returns isn’t simple. Apple, for example,

has paid out more than $64 billion to shareholders through dividends

and stock buybacks since mid-2013, when Mr. Icahn began pressing the

company to stop sitting on so much of its cash. Last month, the

company boosted its dividend by 11% and increased its buyback plan by

$50 billion, to $140 billion.

But Apple also has long pursued a

disciplined approach to R&D that has yielded much bigger payoffs than

companies that spent far more.

Nokia Corp.

outspent the iPhone maker on R&D by a

4-to-1 ratio over the decade starting in 2001 but still ended up an

also-ran in the cellphone market it once dominated.

“The history of corporate America is

littered with a long line of companies that relinquished their leading

industry position and spent enormous resources attempting to reinvent

themselves and ultimately failed,” activist fund Starboard Value LP

wrote in a letter to

Yahoo Inc.

in March as it pushed for a

multibillion-dollar buyback at the technology company.

Yahoo later decided to buy

back $2 billion in stock.

The surge of activism has

sharpened the debate about the fundamental purpose of a company. Does

it exist to satisfy shareholders or does it have an imperative also to

try to build for the long term?

The answer is far from

settled. If the activists are right, they are stopping companies from

throwing good money after bad.

“If they aren’t, then we

have to worry about the impact,” says Yvan Allaire, the executive

chairman of the Institute for Governance of Private and Public

Organizations. “It has to be a fairly significant impact on the

economy.

Write to

Vipal Monga at

vipal.monga@wsj.com, David Benoit

at

david.benoit@wsj.com and Theo

Francis at

theo.francis@wsj.com

|