|

Business Day

Tech Companies Fly High on Fantasy Accounting

JUNE 21, 2015

Technology shares have been powering the stock market recently,

outperforming the broader stock indexes by wide margins. The

tech-heavy Nasdaq 100, for example, is up 19 percent over the last 12

months, almost twice as much as the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index,

which has risen 10 percent.

Investor enthusiasm for all things tech is understandable, given the

disruptions the industry is bringing to so many businesses and the

potential profits associated with that upheaval.

But

there’s a more troubling aspect of the current exuberance for

technology stocks: the degree to which so many of the popular

companies with premium-priced shares promote financial results and

measures that exclude their actual costs of doing business.

These

companies, in effect, highlight performance that is based more on

fantasy than on reality.

Corporations still must report their financial results under generally

accepted accounting principles, or GAAP. But they often play down

those figures, advising investors to focus instead on the numbers

favored by those in the executive suite — who, it just so happens,

stand to gain personally from the finagling.

| |

Fair Game

A

column from Gretchen Morgenson examining the world of finance

and its impact on investors, workers and families

See More »

|

Among

the biggest costs these companies ask investors to ignore are those

associated with stock-based compensation, acquisitions and

restructuring. But these are genuine expenses, so excluding them from

financial reporting makes these companies’ performance look better

than it actually is.

This,

in turn, makes it harder for investors to understand how their

businesses are really doing and whether their shares are overvalued or

fairly priced.

Not

all technology companies encourage the use of funny figures. Apple and

Netflix report only GAAP results. But they are in the minority.

Cooking up funny figures to accentuate the positive at a company is

not a new problem. Justifying rocketing stock prices with kooky

financial metrics was central to the 1999 Internet mania. We all

remember how that ended.

But

while today’s creativity in financial reporting is more down to earth

than it was during the last boom, the use of performance measures that

exclude some basic corporate costs seems to be growing among

companies.

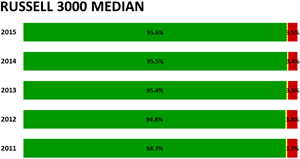

Jack

Ciesielski, publisher of

The Analyst’s Accounting Observer,

studied this issue last fall. For the five years that ended in 2013,

he found that the number of cost items excluded from the reports of

104 large technology, health care and telecommunications companies had

risen to 504 in 2013, up from 365 in 2009.

We’re

talking real money. In 2013, Mr. Ciesielski also found that the

difference between these companies’ GAAP profits and earnings without

the bad stuff was $46 billion in 2013. This was down from 2012, but it

was more than double the amount in 2009.

But

perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the funny numbers used by

companies is the way they serve to raise

executive pay levels. That’s

because these companies often exclude the cost of stock grants awarded

to executives and employees, significantly improving reported

performance.

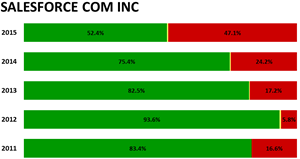

Consider

Salesforce.com, a

supplier of customer management software and services. In spite of

recording a loss from operations of $146 million in fiscal 2015, the

company’s stock is a highflier; its market capitalization is almost

$50 billion.

Investors may be focusing on the revenue growth at

Salesforce.com — up 32 percent

last year and up 34 percent on average in each of the last four years.

Or that the company’s most recent loss was half that generated in

2014.

But

when Salesforce.com computes its executives’ cash incentive pay, its

$146 million operating loss turns into a $574 million operating

profit. This transformation occurs because the company excluded $565

million worth of stock grants awarded to employees last year.

Investors may be growing concerned about these games of pretend. A

sign of the discontent is the increasing support for “say on pay”

measures, in which shareholders express views on company pay

practices.

For

example, at Salesforce.com’s annual meeting this month, 47 percent of

the shares voted

were against the company’s pay

plan. That’s almost twice the 24 percent dissent the company received

from shareholder votes at the 2014 meeting.

Chi

Hea Cho, a spokeswoman for Salesforce.com, said in a statement: “We

describe our pay practices in significant detail in our proxy

statement, including our compensation philosophy and the rationale for

our executive compensation decisions. We value the opinions of our

shareholders and have engaged in an active dialogue with them on

executive compensation practices.”

Ms.

Cho declined to comment on the company’s decision to exclude stock

grants from its performance pay measures. But she pointed me to

company filings, which note that “stock-based expense varies for

reasons that are generally unrelated to operational decisions and

performance in any particular period.”

Brian

Foley, an independent compensation consultant in White Plains,

questioned any company’s exclusion of stock grants when assessing

executive performance.

“One

has to be very disciplined about how you measure performance,” he said

in an interview. “These companies are paying out real value in option

and stock awards every year, and if those awards are such a key

component and driver of overall compensation in such companies, why

isn’t the cost of that key component part of the mix when it comes to

judging annual performance and sizing senior management annual

bonuses?”

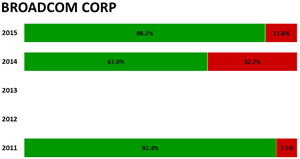

Some companies are changing their practices

after hearing from investors. This year,

Broadcom, a

supplier of integrated circuits, said it would no longer exclude stock

awards from its performance pay measures.

Companies can’t play pretend about the true cost of stock grants in

their regulatory filings, of course. And vigilant shareholders know

that these expenses often become glaringly evident through the prism

of billion-dollar share buybacks conducted by these companies. Many

technology companies have to pursue these repurchase programs to limit

the diluting effect of their generous stock grants. And they pay

handsomely to do so.

Ken

Broad is founding partner and portfolio manager at

Jackson Square Partners, a money

management firm in San Francisco that oversees $30 billion in assets.

He said that it was up to investors to stop accepting performance

figures and analysts’ estimates that exclude real costs.

“Lots

of investors have ever-shorter time horizons and they care less about

what’s embedded in the number than whether the company beat the

consensus estimate,” he said in an interview on Thursday.

Part

of it, too, is bull-market thinking. And when the music stops?

“This

stuff doesn’t matter,” he said, “until it does.”

A version of this article appears in print on June 21, 2015, on page

BU1 of the New York edition with the headline: Flying High on Fantasy

Accounting.

© 2015 The

New York Times Company |