|

Opinion:

What you can do about obscenely high executive pay

Published: July 16, 2015

5:30 a.m. ET

Voting at company meetings isn’t enough — you have to take the matter into

your own hands

|

|

MarketWatch photo illustration/Shutterstock |

Executive compensation in the U.S. is usually discussed in

moral terms. It’s not fair that chief executive officers are paid up to

$156 million a year, the argument

goes.

But those

outsized pay packages, in the form of stock-based compensation, are

financed by shareholders, who suffer a loss in earnings per share and

ownership of the company. And because CEOs are paid mostly in stock, they

tend to obsess over the share price, training them to focus on short-term

company gains.

Total pay

in the past seven years has risen four times faster for executives than it

has for the average worker. A CEO of an S&P 500 member company received a

median $10.1 million in 2013, the last year for which

figures are available. Some

executives’ pay seems as if a decimal point was misplaced, such as that of

Twitter Chief Financial Officer Anthony Noto,

who took home $72.8 million in 2014.

“Basing

compensation on a stock price is creating incentives to increase the stock

price and not necessarily the business fundamentals behind it,” said Gary

Lutin, a former investment banker at Lutin & Co. who oversees the

Shareholder Forum in New York. In an interview, Lutin said measuring

executive performance that way “encourages manipulation of the stock

price.”

Many

investors don’t realize how harmful executive compensation is. In fact,

they typically approve top executives’ pay at annual meetings in

non-binding voting.

But that

may change. And there’s an easy solution that doesn’t involve new rules

and regulations.

Stock-based compensation

Since

2007, the Securities and Exchange Commission has required publicly traded

companies to report the total compensation of their top five executives

for the previous year.

Here’s

information provided by Equilar showing the rise in median total pay for

the top five executives among S&P 500 companies over eight years:

|

Year

|

Median pay for top five executives ($

millions)

|

|

2014 |

$11.5 |

|

2013 |

$10.4 |

|

2012 |

$10.3 |

|

2011 |

$9.8 |

|

2010 |

$9.4 |

|

2009 |

$7.7 |

|

2008 |

$7.7 |

|

2007 |

$6.9 |

|

Source: Equilar |

The median

pay for executives has risen 67%. In 2009, compensation stalled as the S&P

500 Index plummeted 38% the year before.

In

contrast, the average weekly earnings for U.S. workers have risen only

17%:

|

Year

|

Average weekly earnings

|

|

2014 |

$844.08 |

|

2013 |

$825.45 |

|

2012 |

$808.47 |

|

2011 |

$791.35 |

|

2010 |

$771.20 |

|

2009 |

$751.82 |

|

2008 |

$744.18 |

|

2007 |

$723.83 |

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics |

Median

executive pay numbers mask the egregious pay packages for some. Oracle

Corp. founder and Chairman Lawrence Ellison received $67.2 million in

fiscal 2014. The year before, he made $96.2 million.

Oracle’s

shareholders have rejected the company’s executive compensation listed in

its annual proxy statements over the past three years in non-binding “say

on pay” votes.

Most

large-cap U.S. companies include stock-based awards as a part of

executive-compensation packages. The awards typically make up the great

majority of a top executive’s annual pay. Stock-option awards, for

example, accounted for 97% of Ellison’s pay in fiscal 2014.

Oracle

earned $10.96 billion during fiscal 2014. But not every company that hands

out huge awards to executives is profitable. An egregious example is

Twitter. Of CFO Noto’s total compensation last year, stock-based

compensation made up 99.8% of that.

Noto

joined Twitter a year ago, so his total compensation package looks rather

fat for half a year’s work, especially when you consider that Twitter lost

$577.8 million for the year.

Twitter

provides the usual net income or loss, based on generally accepted

accounting principles (GAAP), in its earnings reports. But it highlights

adjusted earnings that excludes the “noncash” expenses for stock-based

compensation. For the first quarter, Twitter’s GAAP net loss was $162.4

million, but adjusted earnings came to $46.5 million, with the main factor

being the exclusion of $182.8 million in stock-based compensation

expenses.

One might

argue that the adjusted earning figure is more important because it

excludes non-cash items. But the stock issuance caused Twitter’s weighted

average diluted share count to rise by nearly 2% in only one quarter. The

$162.4 million net loss came to

42% of revenue, which would be

remarkably high for any company, let alone an unprofitable one.

Stock

awards lower earnings per share. And if a company increases sales and

earnings over a period of years, it’s a good bet that it will “mop up” the

dilution by buying back shares, which will probably be priced much higher.

So dilution hurts earnings per share now, and expensive buybacks in the

future might not be the best use of the company’s capital.

Buybacks

Before the

SEC’s adoption of 10b-18 in 1982, companies that were publicly traded in

the U.S. weren’t allowed to repurchase common shares in the open market.

Buybacks today are commonplace,

as MarketWatch’s Michael Brush has discussed.

When a

company buys back shares, it can mitigate the dilution caused by the

issuance of stock for executive awards. If it buys back enough stock to

lower the diluted share count, earnings per share will rise, and the stock

price can also climb because of the higher demand and lower supply.

Buybacks

have become so prevalent that some companies are even borrowing to fund

share repurchases. Apple Inc., though it had cash, equivalents and

marketable securities of $194 billion at the end of March, has issued

bonds to raise some of the money that funds the repurchases to avoid

repatriating cash held abroad, which would then be taxed. Apple bought

back $45 billion worth of stock in fiscal 2014 and lowered its fiscal

fourth-quarter diluted share count by 6.2%.

Even after

all the buybacks, Apple’s stock trades for 13.9 times its consensus 2015

earnings estimate, considerably lower than the S&P 500 Index’s 17.7.

So Apple

does not appear to be overpaying for the shares it is repurchasing, while

it is borrowing at historically low interest rates. Shareholders are

benefiting from the buybacks because of higher earnings per share, and

it’s obvious that the company is doing well with product innovation.

But

massive buybacks don’t always turn out well for shareholders.

International Business Machines Corp. is a frequently cited example.

New York Times DealBook

summed up IBM’s situation beautifully in October, pointing out that the

company had spent $108 billion on repurchases from 2000 through September

2014, while its revenue was “about the same as it was in 2008.”

From the

end of 1999 through Sept. 30, 2014, IBM’s stock had a total return, with

dividends reinvested, of 114%. That was far better than the 78% total

return for the S&P 500 Index over the same period, but the stagnation of

revenue was disturbing. And IBM’s stock has been quite weak over more

recent periods, down 3% in three years and up 43% in five years. Those

compare to gains of 55% and 93%, respectively, for the benchmark index.

While

buybacks don’t directly cause boards of directors to hand out stock to

executives, they do provide plenty of “cover” by limiting the dilution

effect.

But

buybacks, at what might be near-record-high stock prices, may keep a

company from deploying excess capital through expansion of its business,

product development, efficiency initiatives or acquisitions that could

drive sales and earnings. It might also keep the company from treating its

non-executive employees fairly.

John

Waggoner of the Wall Street Journal recently warned investors to “beware

the stock-buyback craze,” citing recent research by Goldman

Sachs. The amount of companies’ cash spending allocated to buybacks peaked

at 34% in 2007, but hit a low of 13% in 2009, when the S&P 500 tanked.

That makes it seem like many boards of directors are blindly buying back

shares today, with little consideration to prices.

The Boston

Globe recently

discussed this topic in detail,

using Cisco Systems Inc. as an example.

Basing executive awards

on stock performance

According

to a

recent study by James Reda, David

Schmidt and Kimberly Glass of Arthur J. Gallagher & Co., 173 of the top

200 companies included in the S&P 500 had formal long-term incentive plans

for executives. Among this group in 2013, “45% used relative total

shareholder return” for at least part of their measurements of executive

performance.

Rex

Nutting recently said

executives were looting their own companies

at the expense of employees and the long-term health of their businesses

by “using large stock buybacks to manage the short-term objectives that

trigger higher compensation for themselves.”

“If the

reward is based on market pricing, and especially if the reward is really

big, you have to assume that a lot of contestants will play tricks,” said

Lutin of the Shareholder Forum.

It seems

reasonable to expect a CEO to work hard on boosting sales, expanding into

new markets, developing new products, improving efficiency and widening

profit margins. But a focus on lifting the stock price over short periods

might not be a good thing for long-term shareholders. And it is only human

nature for an executive whose pay is based on short-term stock-price

performance to try to push up that price.

Ira Kay, a

managing partner at executive compensation advisory firm Pay Governance,

has a different view. He strongly supports tying executive pay to stock

performance, as well as stock-based compensation.

“An

objective look at the facts would show that stock-based incentives for

U.S. corporate executives has been a great success,” Kay said in a phone

interview. “It is in fact highly motivating to the executives, and they

end up doing a lot of things, reducing costs, buying companies, selling

divisions, diversifying, stock buybacks, raising dividends. They do a lot

of things to benefit shareholders.”

“And, most

importantly, the shareholders completely agree with what I just said,” Kay

said.

The

numbers back that up, based on the results of “say on pay” votes by

shareholders.

In the

1980s, before the big increase in stock-based compensation and buybacks,

and during the leveraged buyout boom, many companies were being bought out

because “those corporations were under-run,” according to Kay.

“They were

sleepy because executives didn’t have enough stock-based incentives,” he

said. “They did try to increase sales and profits, but it was not a

shareholder-value-maximization strategy and left an enormous amount on the

table for other investors [the ones doing the leveraged buyouts] to

harvest.”

So there’s

a lot to be said for and against stock-based compensation. A positive

development, according to the Gallagher & Co. study, is that

executive-compensation plans are becoming more complex and “shareholders

will push incentive design to become even more complex and better

representative of company performance.”

‘Say on pay’

A way

shareholders can put pressure on boards of directors is through say on pay

voting, which was created as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and

Consumer Protection Act of 2010. The non-binding votes take place at

annual meetings, and shareholders can vote yes or no to the previous

year’s compensation packages for a company’s top five executives.

The

Shareholder Forum has a useful Shareholder Support Rankings tool

you can

use to see the results of individual companies’ say on pay votes:

The

default chart shows the median vote support for the S&P 500, and you can

see that Kay was correct in saying shareholders have overwhelmingly

supported corporate pay packages over the past five years. Because of the

six-year-plus bull market, shareholders who are interested enough to vote

are likely to be pleased with the performance of the stocks.

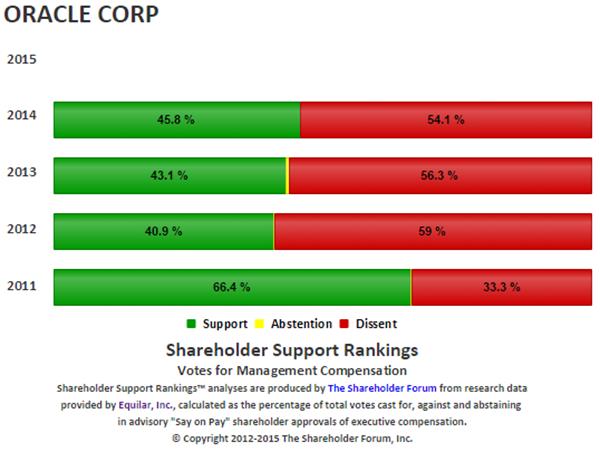

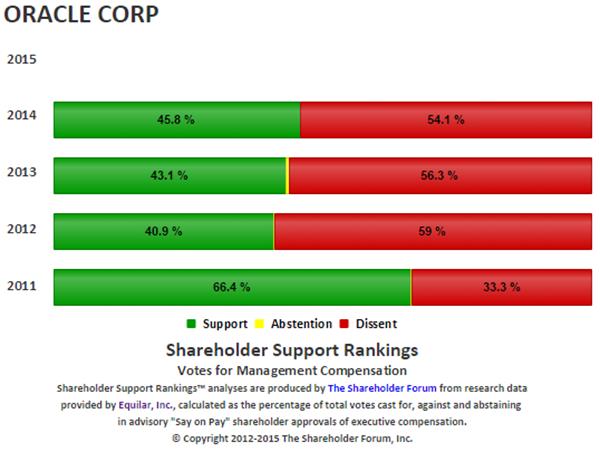

You can

change the ticker in the chart above to any Russell 3000 stock. For example, if

you put in “ORCL” for Oracle, you will see that the company’s pay packages

for its top five executives were soundly rejected by shareholders for

three years running:

|

The Shareholder Forum |

The

majority of Oracle’s shareholders have voted “no” on the compensation

packages for its top five executives for the past three fiscal years.

And here’s

a telling set of numbers for Oracle, showing a decline in total

compensation for its top five executives over the past two fiscal years:

|

Oracle executive

|

Title

|

2014 compensation

|

2013 compensation

|

2012 compensation

|

|

Lawrence Ellison |

Co-Founder, Executive Chairman |

$67,261,251 |

$79,606,159 |

$96,160,696 |

|

Safra

Catz |

Co-CEO |

$37,666,750 |

$44,307,837 |

$51,695,742 |

|

Mark Hurd |

Co-CEO |

$37,668,678 |

$44,309,806 |

$51,697,623 |

|

Thomas Kurian |

President of Product Development |

$26,712,735 |

$31,635,712 |

$36,111,884 |

|

John Fowler |

Executive VP of Systems |

$13,440,526 |

$15,772,439 |

$17,313,173 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

|

$182,749,940

|

$215,631,953

|

$252,979,118

|

|

|

That’s a

big drop — 28% — in only two years, although the executives are still

clearly in the 1% of American earners.

It may

seem unlikely that a board of directors can be “shamed” into lowering

executives’ pay based on the non-binding say on pay votes. But it is still

important for shareholders to vote, because a majority “no” vote might

make directors nervous about keeping their seats when they are up for

reelection.

An item

that may affect say on pay votes is another Dodd-Frank requirement, which

says companies must report the ratio of the CEO to the median employee’s

pay. That could lead to harsh assessments by shareholders. And the media,

of course, will love covering the issue. The SEC has been working on a

final rule for the CEO pay ratio since 2010, and the regulator on June 4

published a memo on various ways to

calculate the ratio.

Politicians to the

rescue?

Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren

has bashed SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White

for the agency’s pace in implementing the requirements of Dodd-Frank.

The

senator is focusing on several items that could change the way top

executives are paid. She said in an interview with the

Boston Globe on June 4 that she had

asked the SEC to take another look at the 1982 rule changes allowing

companies to buy back stock in the open market.

“Stock

buybacks create a sugar high for the corporations,” Warren said. “It

boosts prices in the short run, but the real way to boost the value of a

corporation is to invest in the future, and they are not doing that.”

Warren is

co-sponsoring a bill called the

Stop Subsidizing Multimillion Dollar Corporate

Bonuses Act, which “would revise 1993 legislation that enabled

corporations to tie an executive’s pay to a company’s share price and make

such pay tax-deductible,” according to the Globe.

There may

be little chance of Warren’s bill passing because companies will lobby

hard against it, using the usual currency of campaign contributions for

members of Congress, but it is good for Warren to bring this issue to the

attention of the public.

Radical solutions

Warren’s

bill to ban linking executive compensation to stock-price performance

would be quite a change, but bringing back the ban on open-market buybacks

would be monumental.

Boards of

directors would still be able to award shares to executives if the buyback

ban were restored, but the dilution would no longer be covered up by

buybacks, and new disclosure rules would at least shed light on outsized

awards.

If boards

of directors lost the ability to hand executives massive pieces of company

ownership, they would have to pay the executives a lot of cash. That’s

good, because it would lead to more honest accounting, without the

“noncash expenses” nonsense.

Even

though investors like the idea of executives facing the same risk as they

do, since so much of compensation is based on the stock price, it doesn’t

necessarily work that way when the awards are obscenely large. Banning

bonuses based on stock-price performance would force executives to focus

on running their businesses if they want the big payoff. That would make

it especially important for companies to issue formal incentive programs

laying out financial goals and other objectives for the executives.

A buyback

ban might be a boon to shareholders because executives’ renewed focus on

improving operating performance and expanding over the long term would

make a company’s stock less volatile.

If a

company really does have excess cash and nothing to invest it in, it could

raise its dividend. And dividend payers tend to be more disciplined,

enriching investors in the long run.

What you can do

The coming

SEC rule that requires companies to report a CEO’s compensation as a

multiple to the median employee’s pay will highlight the most outrageous

compensation packages. But the radical step of bringing back the old rule

banning open-market buybacks and companies from measuring executive

performance based on stock-price movement are unlikely to take place.

So if

you’re annoyed by the dilution of your investments or excessive CEO pay,

with “excessive” being defined by you, there is action you can take

besides making your say on pay vote. You can incorporate those concerns

into your stock-selection process.

Lutin of

the Shareholder Forum said the most important thing for individual

investors to do, if they are investing directly in companies rather than

just sticking with mutual funds, ETFs or index funds, is to research a

number companies to find the ones that seem likely to “make real profits

for 10 or 20 years.”

And it

should be relatively easy to spot red flags. “Respect is an important

element,” he said. “It’s also easy to see, since it’s a really basic

element of any organization’s culture. If the people responsible for

running a business show that they don’t respect any key constituencies —

including you, as an investor — you can assume they also don’t respect

others.”

|

Copyright

©2015 MarketWatch, Inc. |

|