|

|

REUTERS/Brendan

McDermid |

As stock buybacks reach historic levels, signs that

corporate America is undermining itself

By

Karen Brettell,

David Gaffen

and

David Rohde

| Filed Nov. 16, 2015, 2:30 p.m. GMT

|

REUTERS |

Combined stock repurchases by U.S. public companies

have reached record levels, a Reuters analysis finds, but as the

recent history of such iconic businesses as Hewlett-Packard and IBM

suggests, showering cash on shareholders may exact a long-term toll.

NEW YORK

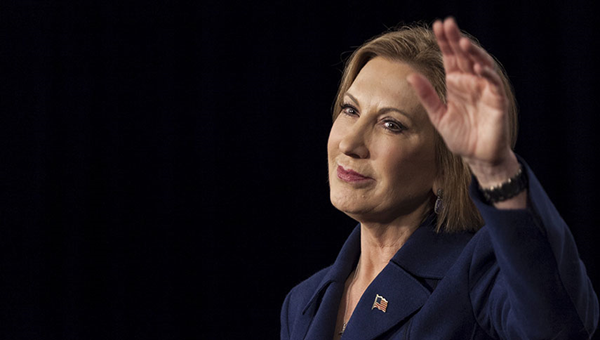

– When Carly Fiorina started at Hewlett-Packard Co in July 1999, one

of her first acts as chief executive officer was to start buying back

the company’s shares. By the time she was ousted in 2005, HP had

snapped up $14 billion of its stock, more than its $12 billion in

profits during that time.

Her

successor, Mark Hurd, spent even more on buybacks during his five

years in charge – $43 billion, compared to profits of $36 billion.

Following him, Leo Apotheker bought back $10 billion in shares before

his 11-month tenure ended in 2011.

The three

CEOs, over the span of a dozen years, followed a strategy that has

become the norm for many big companies during the past two decades:

large stock buybacks to make use of cash, coupled with acquisitions to

lift revenue.

All those

buybacks put lots of money in the hands of shareholders. How well they

served HP in the long term isn’t clear. HP hasn’t had a blockbuster

product in years. It has been slow to make a mark in more profitable

software and services businesses. In its core businesses, revenue and

margins have been contracting.

HP’s

troubles reflect rapid shifts in the global marketplace that pressure

most large companies. But six years into the current expansion, a

growing chorus of critics argues that the ability of HP and companies

like it to respond to those shifts is being hindered by billions of

dollars in buybacks. These financial maneuvers, they argue,

cannibalize innovation, slow growth, worsen income inequality and harm

U.S. competitiveness.

“HP was

the poster child of an innovative enterprise that retained profits and

reinvested in the productive capabilities of employees. Since 1999,

however, it has been destroying itself by downsizing its labor force

and distributing its profits to shareholders,” said William Lazonick,

a professor of economics and director of the Center for Industrial

Competitiveness at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell.

HP

declined to comment for this article.

CEO Meg

Whitman has just overseen one of the largest corporate breakups ever

attempted, creating one company for the PC and printer business,

called HP Inc, and one for the corporate hardware and services

business, called HP Enterprise. Ultimately, HP’s turnaround efforts

and restructuring will cost 80,000 jobs.

A Reuters

analysis shows that many companies are barreling down the same road,

spending on share repurchases at a far faster pace than they are

investing in long-term growth through research and development and

other forms of capital spending.

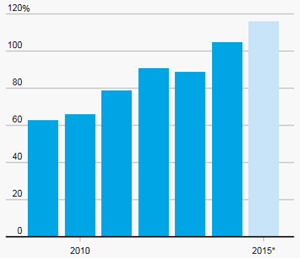

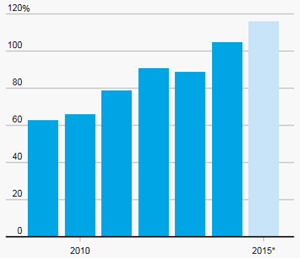

Almost 60

percent of the 3,297 publicly traded non-financial U.S. companies

Reuters examined have bought back their shares since 2010. In fiscal

2014, spending on buybacks and dividends surpassed the companies’

combined net income for the first time outside of a recessionary

period, and continued to climb for the 613 companies that have already

reported for fiscal 2015.

In the

most recent reporting year, share purchases reached a record $520

billion. Throw in the most recent year’s $365 billion in dividends,

and the total amount returned to shareholders reaches $885 billion,

more than the companies’ combined net income of $847 billion.

The

analysis shows that spending on buybacks and dividends has surged

relative to investment in the business. Among the 1,900 companies that

have repurchased their shares since 2010, buybacks and dividends

amounted to 113 percent of their capital spending, compared with 60

percent in 2000 and 38 percent in 1990.

And among

the approximately 1,000 firms that buy back shares and report R&D

spending, the proportion of net income spent on innovation has

averaged less than 50 percent since 2009, increasing to 56 percent

only in the most recent year as net income fell. It had been over 60

percent during the 1990s.

|

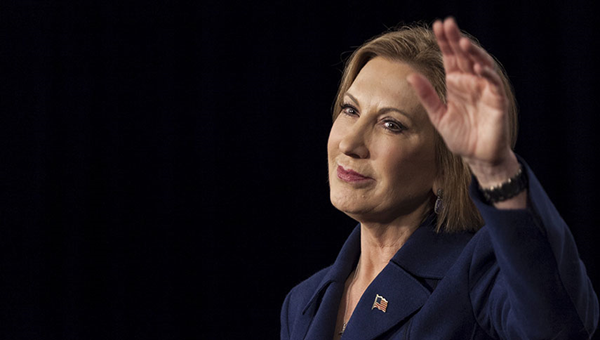

COMPLEX LEGACY: During her tenure as Hewlett-Packard CEO, Carly

Fiorina, now seeking the Republican presidential nomination,

spent $14 billion on buybacks and nearly doubled the company’s

registered patents, but had no big, innovative successes.

REUTERS/Brian C. Frank |

| |

“Even the Wall

Street analyst crowd at some point will say, ‘When are you going

to grow?’ ”

David Melcher, chief

executive, Aerospace Industries Association

|

Share

repurchases are part of what economists describe as the increasing

“financialization” of the U.S. corporate sector, whereby investment in

financial instruments increasingly crowds out other types of

investment.

The

phenomenon is the result of several converging forces: pressure from

activist shareholders; executive compensation programs that tie pay to

per-share earnings and share prices that buybacks can boost; increased

global competition; and fear of making long-term bets on products and

services that may not pay off.

It now

pervades the thinking in the executive suites of some of the most

legendary U.S. innovators.

IBM Corp

has spent $125 billion on buybacks since 2005, and $32 billion on

dividends, more than its $111 billion in capital spending and R&D

during the same period. Pharmaceuticals maker Pfizer Inc spent $139

billion on buybacks and dividends in the past decade, compared to $82

billion on R&D and $18 billion in capital spending. 3M Co, creator of

the Post-it Note and Scotch Tape, spent $48 billion on buybacks and

dividends, compared to $16 billion on R&D and $14 billion in capital

spending.

At

Thomson Reuters Corp, owner of Reuters News, capital spending last

year totaled $968 million, more than half of which went toward R&D,

according to the company’s annual report. Buybacks and dividends for

the year were more than double that figure, at a combined $2.05

billion. The company had 53,000 full-time employees last year, down

from 60,500 in 2011. So far this year, capital spending is at $743

million, while buybacks and dividends total $2.02 billion.

“From a

capital allocation perspective, we will always prioritize

re-investments in our growth priorities over share buybacks,” said

David Crundwell, senior vice president, corporate affairs, at Thomson

Reuters.

“A SCARY

SCENARIO”

In

theory, buybacks add another way, on top of dividends, of sharing

profits with shareholders. Because buybacks increase demand and reduce

supply for a company’s shares, they tend to increase the share price,

at least in the short-term, amplifying the positive effect. By

decreasing the number of shares outstanding, they also increase

earnings per share, even when total net income is flat.

Companies

say buybacks are warranted when demand for their products and services

isn’t enough to justify spending on R&D, or when they deem their

shares to be undervalued, and therefore a better investment than new

projects.

|

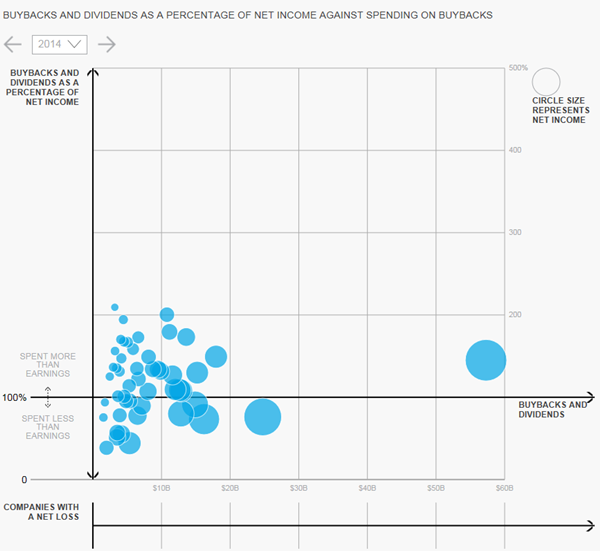

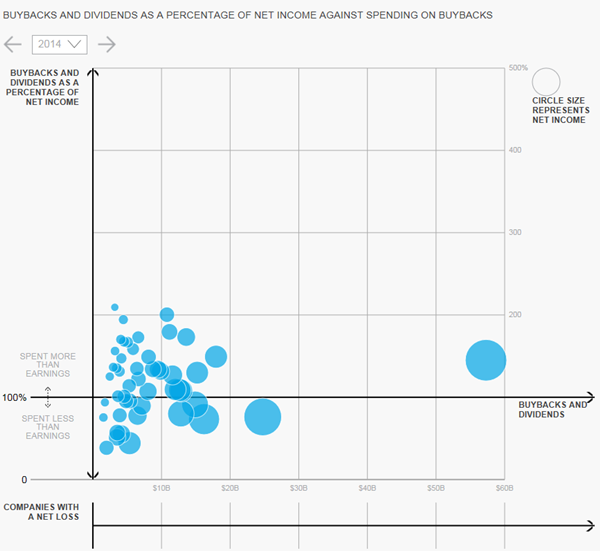

Spreading the Wealth

The top 50 non-financial U.S. companies in terms

of cumulative amounts spent on stock repurchases since 2000 are

now often giving more money back to shareholders in buybacks and

dividends than they make in profits – the first time that’s

happened outside of recessionary periods.

Sources: Thomson Reuters data,

regulatory filings

By Matthew Weber and Karen Brettell | REUTERS GRAPHICS |

But if

those buybacks come at the expense of innovation, short-term gains in

shareholder wealth could harm long-term competitiveness. “The U.S. is

behind on production of everything from flat-panel TVs to

semiconductors and solar photovoltaic cells,” said Gary Pisano, a

professor at Harvard Business School and author of “Producing

Prosperity: Why America Needs a Manufacturing Renaissance.”

If U.S.

companies continue to dole out their cash to investors, he said,

economic investment “will go where it can be used well. If a company

in Germany, India or Brazil has something to do with the money, it

will flow there, as it should, and create growth and activity there,

not in the United States. It’s a scary scenario.”

Even

national security could be threatened as a shrinking defense budget

has made it more difficult for contractors to justify research

spending.

David

Melcher, chief executive of the Aerospace Industries Association, said

companies have turned to buybacks because of a dearth of new weapons

programs and under pressure from Wall Street.

“Their

investment community and the analysts that cover them are all saying,

‘We want a better return and we want EPS to grow,’ ” Melcher said.

“That’s not a sustainable long-term strategy unless all these

companies are going to go private. ... Even the Wall Street analyst

crowd at some point will say, ‘When are you going to grow?’ ”

Among the

largest U.S. defense contractors, Northrop Grumman Corp has spent more

than $12 billion on share repurchases since 2010, even as revenue has

declined in each of the past five years. Lockheed Martin’s revenue has

been flat since 2010; it has spent almost $12 billion on buybacks in

that time.

In recent

months, as the 2016 election campaigns have gathered momentum, concern

about the long-term effects of the buyback craze has crept into public

discourse and caught the attention of politicians.

Democrat

Senators Elizabeth Warren and Tammy Baldwin have called on the

Securities and Exchange Commission to investigate buybacks as a

potential form of market manipulation.

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has made shifting

companies’ short-term focus to the long term a key plank of her

campaign. In July, she proposed increasing taxes on short-term

investments and more rigorous disclosure of share repurchases and

executive compensation. These moves, she said, will foster longer-term

investment, innovation and higher pay for workers.

Fiorina,

now a Republican presidential contender running on her record as a

corporate executive, declined multiple requests for comment.

| |

COMPLEX LEGACY: During her tenure as Hewlett-Packard CEO, Carly

Fiorina, now seeking the Republican presidential nomination,

spent $14 billion on buybacks and nearly doubled the company’s

registered patents, but had no big, innovative successes.

REUTERS/Brian C. Frank

“HP had plenty of

cash to buy back as much stock as it wanted to. … It’s a good

use of capital.”

Mark Hurd, former CEO,

Hewlett-Packard Co

|

Hurd, now

a co-chief executive at Oracle Corp, told Reuters that repurchases

were an appropriate use of capital. “HP had plenty of cash to buy back

as much stock as it wanted to,” he said in an interview. Operating

cash flow during his tenure was $62 billion, a third more than he

spent on buybacks. “It’s a good use of capital,” he said.

HP’s

revenue and share price rose while Hurd was in charge. He said

decisions about the size of stock buybacks and investment in R&D,

which totaled $17 billion during his tenure, were not related.

A

spokesman for Apotheker, Hurd’s successor, declined to comment.

Until

1982, companies were largely prohibited from buying their own shares.

That year, as part of President Ronald Reagan’s broad moves to

deregulate financial markets, the SEC eased its rules to allow

companies to buy their own shares on the open market.

At the

time, free-market reformers argued that corporate America had become

fat and wasteful after decades of postwar growth, with no checks on

how managers spent cash – or didn’t.

“The

boards you had were managers themselves and their friends,” said

Charles Elson, finance professor and director of the John L. Weinberg

Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware. “It was

basically managerial power, unchecked.”

Over the

years, however, a belief has taken hold that companies’ primary

objective is to maximize shareholder value, even if that means paying

out now through buybacks and dividends money that could be put toward

long-term productive investments.

“Serving

customers, creating innovative new products, employing workers, taking

care of the environment … are NOT the objectives of firms,” Itzhak

Ben-David, professor of finance at Ohio State University’s Fisher

College of Business and a buyback proponent, wrote in an email

response to questions from Reuters. “These are components in the

process that have the goal of maximizing shareholders’ value.”

That goal

has come to the fore in some high-profile cases of late as activist

investors have demanded that executives share the wealth – or risk

being unseated.

In March,

General Motors Co acceded to a $5 billion share buyback to satisfy

investor Harry Wilson. He had threatened a proxy fight if the auto

maker didn’t distribute some of the $25 billion cash hoard it had

built up after emerging from bankruptcy just a few years earlier.

DuPont

early this year announced a $4 billion buyback program – on top of a

$5 billion program announced a year earlier – to beat back activist

investor Nelson Peltz’s Trian Fund Management, which was seeking four

board seats to get its way. Even so, CEO Ellen Kullman stepped down in

October after sales slowed and the stock slid.

In March,

Qualcomm Inc, under pressure from hedge fund Jana Partners, agreed to

boost its program to purchase $10 billion of its shares over the next

12 months; the company already had an existing $7.8 billion buyback

program and a commitment to return three quarters of its free cash

flow to shareholders. Still, the stock had been underperforming the

S&P 500 for most of the past 10 years.

Jana

wasn’t satisfied, and in July, Qualcomm announced it would shed nearly

5,000 workers, among other moves to cut costs. R&D spending, it said,

would stay at around $4 billion a year.

Managers

ignore shareholder demands at their own risk, especially when the

share price is under pressure. “None of it is optional. If you ignore

them, you go away,” said Russ Daniels, a technology and management

executive who spent 15 years at Apple Inc and then 13 years at HP,

where he was chief technology officer for enterprise services when he

left in 2012. “It’s all just resource allocation. … The situation

right now is there are a lot of investors who believe that they can

make a better decision about how to apply that resource than the

management of the business can.”

| |

POLITICAL INTEREST: Democratic presidential candidate Hillary

Clinton has recently decried companies’ focus on the short term

and voiced support for measures to foster long-term growth and

innovation. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

Maximizing

shareholder value has “concentrated income at the top and has

led to the disappearance of middle class jobs.”

William Lazonick, professor

of economics, University of Massachusetts-Lowell

|

IBM Corp,

once the grande dame of U.S. tech companies, spent $5.43 billion on

R&D in the most recent year. It has been spending a lot more on

buybacks.

For

decades, the computer hardware, software and services company has

linked executive pay in part to earnings per share, a metric that can

be manipulated by share repurchases. Since 2007, IBM’s per-share

earnings have surged 66 percent, though total net income has risen

only 15 percent. (The company says in regulatory filings that it

adjusts for the impact of buybacks on EPS when determining pay

targets.)

IBM has

been among the most explicit in its pursuit of higher per-share

earnings through financial engineering. In 2007, in communications

with shareholders, it laid out the first of its “road maps” for

boosting EPS, this time to $10 a share by 2010. It would do so, under

the plan, through equal emphasis on improved margins, acquisitions,

revenue growth, and share repurchases. It easily met its expectations.

In 2010,

then-CEO Sam Palmisano doubled down, pledging to boost earnings by

more than 75 percent to $20 a share by 2015. This time, more than a

third of that increase was expected to come from buybacks. Palmisano

left in 2011, having received more than $87 million in compensation in

his last three years at the company.

For a

while, the plan worked. Shares surged to an all-time high of $215 in

March 2013. But the company’s operating results have lagged.

Revenue

has declined for the past three years. Earnings have fallen for the

past two. The stock is down a third from its 2013 peak, while the S&P

500 has risen 34 percent. To rein in costs, IBM has cut jobs. It now

employs 55,000 fewer workers than it did in 2012.

“Morale

is not too good when you see these cuts,” said Tom Midgley, a 30-year

veteran of IBM’s Poughkeepsie, New York, plant. In recent years, he

said, his wage increases have shrunk, as has the company’s

contribution to 401(k) retirement savings.

IBM

spokesman Ian Colley said that the company’s results have been hurt by

currency shifts and business divestitures. He said that the company

continues to grow, and that its buybacks have not affected research,

development and innovation efforts. “IBM prioritizes investment in the

business,” he said, citing recent acquisitions in cloud and other

areas.

WEALTH

BENEFIT

Share

repurchases have helped the stock market climb to records from the

depths of the financial crisis. As a result, shareholders and

corporate executives whose pay is linked to share prices are feeling a

lot wealthier.

That

wealth, some economists argue, has come at the expense of workers by

cutting into the capital spending that supports long-term growth – and

jobs. Further, because most most U.S. stock is held by the wealthiest

Americans, workers haven’t benefited equally from rising share prices.

| |

Buybacks

and dividends as a percentage of net income

Note:

Aggregate number for 3,297 publicly traded non-financial

companies analyzed by Reuters

*2015

data for 613 companies that have reported

Sources: Thomson Reuters data, regulatory filings

By

Matthew Weber and Karen Brettell | REUTERS GRAPHICS

|

Thus,

said Lazonick, the economics professor, maximizing shareholder value

has “concentrated income at the top and has led to the disappearance

of middle-class jobs. The U.S. economy is now twice as rich in real

terms as it was 40 years ago, but most people feel poorer.”

Paul

Bloom, who was an executive at IBM for 16 years, including chief

technology officer for telecom research before leaving in 2013, is

among the optimists who argue that venture capital and other

alternative channels of R&D investment will take up some of the slack,

supporting innovation and economic growth.

Now a

consultant to venture capital firms, Bloom expects large companies to

shift away from investing directly in R&D, focusing instead on

acquiring startups and spinning off experimental projects that will be

less constrained by bureaucracy and Wall Street demands. “You are

going to see more and more corporate investing in the startups than

you have in the past,” he said.

Many of

the transformative breakthroughs of the past century – light bulbs,

lasers, computers, aviation, and aerospace technologies – were based

on innovations coming out of the labs of companies that could afford

rich funding, like IBM, Apple, Xerox Corp and HP.

Some say

a technological shift at companies like HP and IBM away from

traditional manufacturing, which requires large investments in

buildings and equipment, and toward data-based products is also

changing the calculation of how much investment is needed in

innovation.

“The way

these companies spend dollars is different, the type of investment is

hard to count. While you might think their spending is flat, I think

it’s better utilized,” said Mark Dean, who worked in R&D for 34 years

at IBM and was a member of the team that created the first personal

computer in 1981. “Innovation is changing.”

THE HP

WAY

For

years, HP adhered to “the HP way,” a widely admired egalitarian

corporate philosophy. Operating divisions were given broad autonomy to

develop their businesses. Employees were encouraged to think

creatively in a nurturing environment. R&D spending regularly topped

10 percent of revenue.

When

Fiorina arrived in 1999, she upended that, implementing companywide

layoffs, shifting jobs overseas and centralizing control.

Bill

Mutell, a former HP senior vice president who joined from Compaq

Computer Corp after HP paid $25 billion for it in 2001, spoke to

Reuters at the suggestion of Fiorina’s presidential campaign. He said

that changes she implemented were needed because the company had

become sluggish at innovation. HP would “aim, aim, and aim, and there

was never any implementation and execution,” he said.

Fiorina

joined soon after the company had spun off what is now Agilent

Technologies, the arm that housed much of the company’s high-tech

expertise.

In R&D,

she focused on winning patents as a measure of the effectiveness of

spending. The number of HP-registered patents rose from 17,000 in 2002

to 30,000 when she left in 2005, according to regulatory filings.

Even so,

all of those new patents failed to yield any enduringly successful

innovations. R&D efforts were scattered, and some projects overlapped.

Fiorina’s

compensation was linked in part to earnings per share when she joined

in 1999. And from 2003, it was also linked to something called total

shareholder return, a measure of performance, including stock-price

appreciation plus dividends, that was then compared to returns for the

S&P 500 Index.

Fiorina’s

buybacks failed to stop HP’s share price slide after the dot-com

bubble burst in 2000. Uneven earnings and concern about the Compaq

acquisition whipsawed the share price during her tenure, helping lead

to her ouster in 2005.

| |

IN AND OUT: Leo Apotheker, Hurd’s successor at HP, presided over

a disastrous acquisition and $10 billion in stock buybacks

during his brief 11-month tenure as CEO. REUTERS/Stephen Lam

Some managers

struggling to meet Hurd’s targets implemented spending freezes

as the end of a quarter neared, halting procurement of supplies,

according to former HP engineers. |

Hurd

streamlined the company’s structure, which had ballooned after the

Compaq acquisition. He slashed the number of research projects, from

6,800 to about 40, and cut costs across the company’s PC and printer

divisions, focusing instead on building higher-margin software and

services businesses.

Market

share in each division grew. But in the PC and printer divisions,

researchers said, new limits on spending disrupted project timelines.

Some managers struggling to meet Hurd’s targets implemented spending

freezes as the end of a quarter neared, halting procurement of

supplies, according to former HP engineers.

“You

can’t turn it on and off like a faucet, turn it off one quarter to

make the quarterly results look good, then turn it back on next

quarter and have great products coming out the other end,” said a

former HP engineer.

Engineers

at HP who had previously created prototypes at U.S. facilities were

also now relying on Asian manufacturing sites to build them. Travel to

these regions was on occasion delayed due to spending pressures.

Workers at the company’s labs were also moved off the more

experimental projects and realigned to work on existing product lines.

In the

interview, Hurd said he wasn’t aware of any spending freezes or

project disruptions.

The

changes he implemented led to sparkling results: From 2005 to 2010,

net income rose 265 percent on a much smaller 45 percent increase in

revenue. HP’s stock price more than doubled, from $20 to $50, during

his tenure.

Thanks to

hefty stock buybacks, earnings per share did even better, increasing

350 percent. HP increased share repurchases from $3.51 billion in 2005

to $7.78 billion in 2006, and again to more than $9 billion a year in

four of the next five years. (Roughly 20 to 30 percent of annual

repurchases offset dilution from employee stock-purchase plans.)

Hurd said

improving revenue and market share during his term was always his

first concern.

“The

share price is the result that occurs if the company is performing

well,” he said. “Short-term tricks to try to improve EPS, and

eventually share prices, usually don’t work. ... Going out and saying

I’m going to cut a dividend, make a one-time buyback, these are sort

of like parlor tricks, they aren’t sustainable.” He said he declined

shareholder requests that ranged from increasing dividends to adopting

a specific EPS plan like IBM’s “road map.”

Because

he nearly always met per-share earnings and other targets, his pay

mostly rose, too. In 2008, for example, it jumped to $42 million from

$25 million the year before. (It fell in 2009 to $30 million when he

failed to meet targets.)

Investors

were impressed by the turnaround. Operating margins, which had dropped

below 5 percent under Fiorina, rose as high as 9 percent under Hurd,

and the share price soared 200 percent.

Hurd

resigned in August 2010 amid a scandal involving his relationship to

an HP contractor.

His

successor, Leo Apotheker, spent just shy of a year at the helm, marked

by his decision to buy software firm Autonomy for $11 billion in

October 2011. A year later – after Apotheker left – HP said an

investigation had uncovered accounting fraud at Autonomy before the

purchase. It took a charge against earnings of nearly $9 billion.

CEO

Whitman has attempted to strike a balance with HP’s plans to move into

a growth mode from a turnaround effort. R&D spending rose slightly to

$3.45 billion in 2014, the highest since 2008, even as revenue

declined. At the same time, share repurchases rose to $2.7 billion,

from $1.5 billion in 2013.

Post

breakup, her immediate challenge is to build the higher-margin HP

Enterprise. Both companies will continue with generous buyback

programs. HP Enterprise said in September that it expects to give

shareholders at least 50 percent of free cash flow next year through

buybacks and dividends. HP Inc said it will give back 75 percent.

—————

The Cannibalized Company

By Karen Brettell, David Gaffen and David Rohde

Data: Karen Brettell

Graphics: Matthew Weber

Edited by John Blanton |