|

Are Activist Hedge Fund Managers to Blame for Mega-Deal Failures?

By

Ronald Orol

|

04/26/16 - 03:50 PM EDT

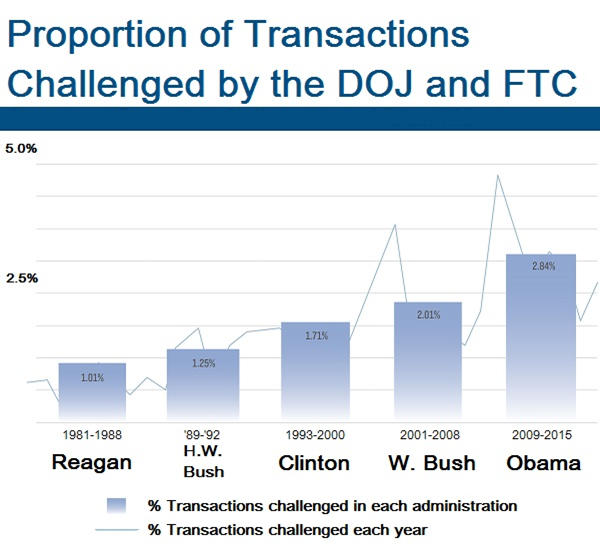

Over the

past several years, a wave of huge mergers have been challenged and,

ultimately, blocked by the federal government.

Using data

from the Federal Trade Commission and

The Deal, a subsidiary of

TheStreet.com, TheStreet has discovered a pattern of increased

regulatory actions challenging mergers that dates back to the Reagan

administration. Under President Obama, the FTC, DOJ and other

regulatory bodies have challenged and blocked a higher proportion of

U.S. deals than ever before. At the same time, deals are getting

bigger and more complicated. Call it "Big

Business vs. Big Government."

|

|

Each administration since Ronald

Reagan has challenged a larger proportion of mergers, TheStreet

has discovered. Source: Hart-Scott-Rodino Act filings with the

FTC. |

While the

government has certainly been more active in affecting deal activity

than in years past, is an overaggressive Uncle Sam the only culprit

for this new era of deal-busting?

Activist

hedge fund managers and, in some cases, analysts, are to blame, too.

"Many

antitrust-sensitive mergers were driven by activist hedge funds,"

contends Kai Liekefett, a partner and head of the shareholder activism

response team at law firm Vinson & Elkins. "Activists have the luxury

that they can take their profits and run following the announcement of

a proposed merger. By the time the merger experiences pushback from

the antitrust authorities many months later, the activists may have

already divested some or all of their position, leaving the merger

parties holding the bag."

Probably

the most explicit example of an activist fund that drove a deal gone

wrong involves activist Starboard Value's Jeff Smith (pictured)

2015 campaign at both Staples (SPLS)

and Office Depot (ODP)

to push for the two companies to consider a merger.

Starboard

accumulated large stakes in both office supply companies and had been

eyeing a March 2015 Staples board deadline to nominate director

candidates, according to people familiar with the situation, as part

of an effort press the two companies into a combination. The two

office supply chain companies agreed in February, 2015 to combine in a

blockbuster $6.3 billion deal that was

subsequently challenged in December

by the Federal Trade Commission, which said the deal would

violate antitrust laws by reducing competition.

The

Starboard push, in retrospect, may have been motivated partly by a

much-publicized September 2014 Credit Suisse analyst report,

which said a combination between the two box-store office supply

giants "makes significant and operational sense." The note suggested

that a possible combination was "synergistic" and had been

"essentially blessed" by the Federal Trade Commission's wording of an

Office Depot-Office Max approval documents from 2013.

The deal

may still go through, most likely with concessions, but Starboard has

since liquidated its Staples stake and appears on the road to doing so

with Office Depot.

The more

problematic deals are being driven by the activist push, said Deborah

Feinstein, director of the Federal Trade Commission's Bureau of

Competition.

"You wonder

who is counseling that these [deal proposals] are going to be OK or

whether there is such activist pressure that [deal ideas] got out of

boardroom when they shouldn't have," Feinstein said. "In a lot of

these cases we're talking about the number one and two players in

industries merging. Most people would take a deep breath and ask, 'Is

this a good idea and is this one worth the risk?'"

The

now-rickety Halliburton (HAL)

-Baker-Hughes (BHI)

is another good example. Activist investors Jeff Ubben from ValueAct and

his team had been key agitators seeking to drive the $35 billion

acquisition by Halliburton of Baker Hughes, a combination that earlier

this month was hit with a Justice Department

lawsuit seeking to have combination stopped.

In fact, the fund might have gone to improper lengths to push the

deal. Deep Dive: Will

the Halliburton-Baker Hughes Deal Survive Government Opposition?

A couple

days before filing suit against the deal, the DOJ filed a related

lawsuit against ValueAct itself,

arguing that it improperly purchased substantial stakes in both

Halliburton and Baker Hughes "with the intent to influence the

companies' business decisions as the merger unfolded." According to

the Justice Department, ValueAct sent a memorandum to its investors

outlining a strategy of being a "strong advocate for the deal to

close." It added that if the deal encountered "regulatory issues"

ValueAct "would be well positioned" to "help develop new terms."

Embattled

activist investor Bill Ackman and his Pershing Square Capital

Management are also part of this costly trend. Ackman was a key

contributor to Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) lengthy

but ultimately cancelled hostile effort to buy Norfolk Southern (NSC).

Ackman, a major Canadian Pacific shareholder and a director on the

railroad company's board since 2012, had called Norfolk "an ideal

activist situation."

Canadian

Pacific on April 11 cancelled its efforts after Bill Baer, head of the

Antitrust Division at the Justice Department, in March

raised concerns about pre-merger

coordination between the two companies. Four days before the bid was

called off, the chief lawmaker on the House Transportation Committee

piled on by also publicly taking issue

with the transaction, suggesting it is not in the best interest of the

U.S. freight industry. Ackman has long been an advocate of railroad

industry consolidation and was also behind Canadian Pacific's

unsuccessful 2014 run at CSX Corp.

The Justice

Department last month announced it was extending its antitrust

investigation of the proposed $130 billion merger and later break up

of Dow Chemical (DOW)

and DuPont (DD).

The deal would

create the world's largest chemical company--at

least until the companies carry out their plan to break the merged

firm into three separate ones focusing on agriculture, material

science and specialty products. Opponents of that highly complicated

multi-faceted deal can look to activists Third Point and

Trian Fund Management as at least partly to blame there. Deep

Dive: Top

Antitrust Regulator Debbie Feinstein Q&A

Trian's

Nelson Peltz waged an unsuccessful proxy campaign against DuPont last

year. But he threatened to come back in 2016 and in the months

following his defeat DuPont stock price dropped and it subsequently

replaced CEO, Ellen Kullman. The companies said that merger

discussions began soon after that CEO switch. And separately, Third

Point's Dan Loeb, another frequent deal agitator, in 2014 settled with

Dow to install two dissident nominees on the chemical giant's board.

Upon the Dow-DuPont deal's announcement, Loeb said in a letter he

supported it but questioned the timing and called for Dow CEO Andrew

Liveris to be removed.

Shareholders and regulators should watch this development closely. The

costs of failure to obtain approval for a deal can be huge.

Halliburton, for example, agreed to pay a $3.5 billion reverse

termination fee to Baker Hughes if antitrust approval could not be

obtained.

And

activists appear to be able to make money on deals even if the merging

companies end up being sued by the government. Starboard accumulated

shares to reach a 5.1% stake in Staples at prices ranging from $12.00

to $13.92 a share in October and November of 2014, according to a

December 2014 securities filing. The fund in February reported that it

had began liquidating its Staples stake --

shortly after the FTC filed its complaint to block the deal

-- by selling shares to bring it to below a 5% stake at prices between

$16.75 and $17.15 a share. Staples shares traded late Monday at $10.39

a share.

With all

the blockbuster deal challenges, DOJ threats and cancelled deal

efforts, one wonders whether activist fund managers will still be

pushing for mega mergers in the months to come. And if they do,

whether corporate executives will push back harder.

-- Bill

McConnell contributed to this report

© 1996-2016 TheStreet,

Inc. |