|

THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

Tech

Startup Employees Invoke Obscure Law to Open Up Books

Delaware law is potentially valuable tool for employees and

investors who now question their shares’ worth

|

Shareholders are asking companies such

as Domo Inc. to open up their books. Above, a wall board in

Domo’s American Fork, Utah, office. PHOTO: JEFFREY D. ALLRED/THE

DESERET NEWS/ASSOCIATED PRESS |

By

Rolfe Winkler

May 24, 2016 5:30 a.m. ET

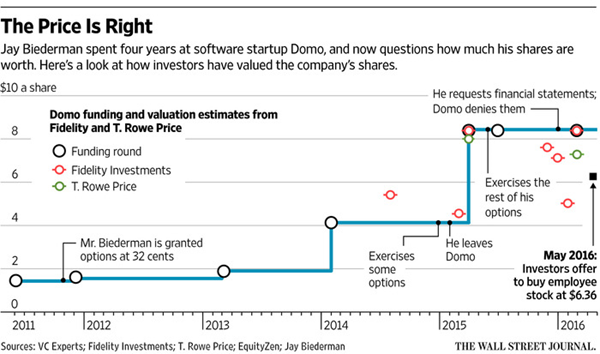

For more than a year, Jay

Biederman has pestered Domo Inc. for its financial statements. The

former executive wants to estimate how much his tens of thousands of

shares in the tech startup are worth.

Domo, whose software

analyzes corporate data, has rejected those requests, he said, keeping

its financial records under wraps like most privately held startups.

But the law may be on Mr.

Biederman’s side.

He recently discovered

section 220 of Delaware’s corporate law, which can compel locally

incorporated companies such as Domo to open up their books to

shareholders. The law, little known in Silicon Valley, is a

potentially valuable tool for thousands of tech workers who received

stock awards to join fast-growing startups, as well as other small

investors, who now question their shares’ worth.

To take advantage of the

law, stockholders must simply prove they own at least one share and

send the company an affidavit that states which documents they want

and why. The magic words for unlocking financial information? “ ‘For

the purpose of valuing my shares,’ ” says Michael Halloran, a

securities lawyer with Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP.

Companies must then comply

or face the possibility of legal action. Shareholders are backed by

strong case law, say lawyers. To keep their financial data private,

companies often ask the shareholder to sign a nondisclosure agreement.

Valuations of private tech

companies are in doubt after years of hype and seemingly endless cash

from venture investors lifted values to new heights. Many of those

investors are now stepping back, pushing startups to deliver profit

over growth. Mutual-fund firms are marking down their stakes in some

startups, adding to the confusion. And the market for tech initial

public offerings is all but shut, another sign startups are

overvalued.

As companies stay private,

their financials remain concealed. Only top investors typically

receive periodic updates on revenue, profits and financial

projections.

Some highly valued

companies, such as software firm Palantir Technologies Inc. and

ride-hailing company Uber Technologies Inc., share little if any

information with smaller shareholders, say people familiar with the

matter. Spokeswomen for the two companies declined to comment.

Companies say keeping

their financial information private, even from some stockholders,

prevents it from falling into rival hands. The lack of public scrutiny

also gives them freedom to invest for the long term.

With at least 145 private

companies including Domo now valued at $1 billion or more, the

financial secrecy has caught the attention of the Securities and

Exchange Commission’s chairman,

Mary Jo White.

“Our collective challenge

is to look past the eye-popping valuations and carefully examine the

implications of this trend for investors, including employees of these

companies,” Ms. White said in a March 31 speech, while also raising

concerns about the accuracy and availability of financial information.

There have been hundreds

of Delaware lawsuits to inspect company books says Ted Kittila, an

attorney with Greenhill Law Group. Most requests are settled before a

suit is filed, he says.

Some companies are now

pushing employees to waive their right to inspect the books as a

condition for receiving stock awards, says Richard Grimm, an executive

compensation attorney. Fitness tracking company

Fitbit Inc.

and online dating site Zoosk Inc.

both did so as private companies, according to their IPO filings.

Fitbit declined to comment. Zoosk didn’t respond to questions.

“It’s unclear whether this

kind of waiver would be supported” in court, Mr. Grimm says.

Option holders at some

larger private companies are supposed to receive financial information

upon request, according to an SEC rule. It is unclear whether all

private tech companies covered under the rule are complying, lawyers

say.

Chris Biow, a former

executive and shareholder at MarkLogic Inc. and MongoDB Inc.—two

software startups valued at over $1 billion—says he regularly

discusses Delaware inspection rights with groups of employees for each

company.

“We have all these

‘unicorns,’ where it’s not clear what year or decade they may go

public,” said Mr. Biow, now a senior vice president at Basis

Technology Corp., using a tech industry term for private companies

valued over $1 billion.

Mr. Biow said he wants to

know the revenue and profits as well as the list of stockholders,

which may be the only possible buyers of his shares as private

companies often restrict sales to new investors.

San Carlos, Calif.-based

MarkLogic, valued at $1 billion by investors a year ago, eventually

agreed to let Mr. Biow view its financial results in its office in

2014, though it has refused to share a full stockholder list, he said.

A MarkLogic spokesman said

the company’s practice “is to be forthcoming with our financial

information for any shareholder that makes a proper request to the

company.”

Mr. Biow only recently

exercised his MongoDB stock options so he hasn’t yet asked the New

York company for information.

Meanwhile, Mr. Biederman,

who left Utah-based Domo in February 2015 after four years, says he is

still trying to get information from the company. This January, Domo’s

treasurer denied access, saying it wasn’t sharing financial data with

stockholders, Mr. Biederman said. A month later he submitted an

affidavit citing his rights under Delaware law.

Since he filed the

affidavit, two divergent signals have exposed the difficulty in

valuing his shares. In February, Fidelity Investments marked down its

Domo shares to $5.03 a share, 40% below where the company previously

sold shares that equated to a $2 billion valuation. A few weeks later,

in March, Domo said it raised more capital at the same $2 billion

valuation, and Fidelity subsequently marked its shares back up to

$8.43 a share.

Then last week, trading

firm EquityZen Inc. sponsored an offering to buy shares from employees

at $6.36, according to a presentation reviewed by the Journal. An

EquityZen spokesman declined to comment.

Mr. Biederman, who last

year exercised his options at 32 cents a share, said the company has

asked him to sign a nondisclosure agreement before sharing financial

information. He says Domo has yet to send it to him.

A Domo spokeswoman

declined to comment.

Write to

Rolfe Winkler at

rolfe.winkler@wsj.com

Tech

Own Startup Shares? Know Your Rights to Company Financials

By

Rolfe Winkler

May 24, 2016 5:30 a.m. ET

Privately held startups

have fewer disclosure requirements than their publicly traded

counterparts. But in the eyes of their employees and shareholders,

private companies shouldn’t be so private.

At least three laws

require startups to disclose financial information to their

stockholders, but lawyers say many don’t comply. Here’s what

shareholders need to know.

Delaware General

Corporations Law, Section 220

Delaware

law gives shareholders of companies

incorporated in the state the right to inspect a company’s books

and records, which can include a list of stockholders, financial

statements, articles of incorporation and more.

Since most tech companies

are incorporated in Delaware, this law applies to most venture-funded

startups.

Ted Kittila, a Delaware

lawyer at Greenhill Law Group, says the following steps should enable

shareholders to inspect financial information to help value their

shares:

Prepare an affidavit that

states:

•That you are a

shareholder. Options don’t count, though exercising one option to buy

one share does.

•The reason to inspect the

company’s books. Delaware courts have said one legitimate reason is

“for the purpose of valuing my shares.”

•The requested documents.

Stockholders might request a balance sheet, income statement and

cash-flow statement to analyze the company’s business. They might also

request a stockholder list to determine how many shares are

outstanding to calculate their percentage ownership.

Companies have five days

to respond. If the company doesn’t reply or rejects the request,

shareholders can file a lawsuit.

A negotiation typically

ensues, including a demand by the company that the shareholder sign a

nondisclosure agreement. If both parties agree, the company should

disclose the documents.

Mr. Kittila says

shareholders could expect to pay about $5,000 in legal costs to draft

a legal letter and negotiate with the company, or more if a lawsuit is

filed. Shareholders may increase their odds of success, and share

legal costs, by teaming up with one another on the same request, he

said.

California Corporations

Code, Section 1501

An

obscure California law requires

larger startups based in the state to send an annual report with

financial statements to all shareholders.

Section 1501 applies to

all companies with headquarters in California, whether or not they are

incorporated in Delaware, says Keith Bishop, the state’s former

commissioner of corporations, now a corporate attorney at law firm

Allen Matkins. The exception is for companies with fewer than 100

shareholders who waive the requirement in their bylaws.

That means the law likely

encompasses dozens of private technology companies valued north of $1

billion, as well as hundreds of smaller tech startups.

The law states the annual

report should include a balance sheet as of the end of the fiscal

year, and income and cash-flow statements for that fiscal year.

Lawyers say most companies

ignore the law because they either aren’t aware of it, or they don’t

want to share their information. Penalties for violating it top out at

$1,500, Mr. Bishop said.

Companies are supposed to

send their annual report within 120 days after the end of its fiscal

year. If they don’t, Mr. Bishop makes the following recommendations:

•Shareholders should send

a letter requesting financial statements, citing Section 1501(a) of

the California Corporations Code. Include a return receipt for proof

of delivery. The company is required to send financials within 30

days, if the request is made more than 120 days after the fiscal

year’s end.

•A shareholder, or group

of shareholders, owning at least 5% of the company can also request

interim financial statements.

•If the company refuses to

provide financials, a shareholder will have to hire a lawyer and file

suit.

•Shareholders should keep

track of expenses like attorney’s fees because the court may force the

company to pay them if it finds it withheld financial statements

without justification.

Federal Securities Act of

1933, Rule 701

Many tech startups lure

new hires with stock options, letting them buy shares at a specified

price. But it can be daunting for option holders to figure out when

and whether to exercise the shares.

Under

this federal securities rule,

option holders at some larger private companies are entitled to

receive detailed financial information when deciding whether to

exercise the options. This includes financial statements, risk factors

and more.

This provision to provide

information is part of a larger rule that helps companies stay private

by exempting stock awards from being registered publicly. But if a

company’s stock awards eclipse $5 million in any 12-month period, the

provision is triggered. Many “unicorn” companies, or those valued at

$1 billion or more, have passed this threshold, say lawyers.

Google and its general

counsel,

David Drummond, got into hot

water with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2005 for

violating this rule when it was a private company.

Google settled with the SEC by

agreeing to abide by the law in the future.

When complying, companies

often give employees access to a password-protected website with

financial information. Option holders are often required to sign a

nondisclosure agreement first, says Daniel Neuman, an attorney with

Carney Badley and Spellman.

Former employees holding

options are also included under this rule, but lawyers say many

companies refuse to provide information to them. People who have left

or been fired typically have 90 days to exercise vested options or

forfeit them.

Lawyers recommend options

holders ask the company if it is required to make disclosures under

rule 701, and request additional information if so.

If the company rejects the

request, option holders can file a complaint with the SEC by

emailing or filling out a

complaint form

here.

Write to

Rolfe Winkler

at

rolfe.winkler@wsj.com

|