In Defense of Fairness

Opinions: An Empirical Review of Ten Years of Data

Posted by Robert Bartell and Christopher

Janssen, Duff & Phelps, on Wednesday, April 19, 2017

|

Editor’s Note:

Robert Bartell is Global Head of Corporate Finance and

Christopher Janssen is Global Head of Transaction Opinions at

Duff & Phelps. This post is based on a Duff & Phelps publication. |

Questions about

the utility of fairness opinions have periodically seized headlines for many

years. As the leading fairness opinion advisor, we can readily speak to the

value of the opinions we provide and the best practices we observe in rendering

them. But when addressing broad industry criticisms—in particular that fairness

analyses generally provide valuation ranges too wide to be useful and that they

are too reliant on “mechanical” discounted cash flow (DCF) analyses—our

arguments have lacked the force of empirical data beyond our own client work.

Until

now. This post—the compilation, review and analysis of more than 3,000

fairness opinions—is the culmination of our efforts to address those

criticisms with research. We believe it does that.

We also believe

that the post itself can serve as a valuable tool for boards evaluating purchase

offers.

Directors seeking

fairness opinions have long been left to rely on their own intuition and

experience in scrutinizing valuation estimates. Our post provides them with a

set of benchmarks, drawn from federal filings, for comparison. They’ll now know

when a fairness opinion’s estimate falls outside the average valuation range

against the offer price for similar-sized deals. Our post should empower

directors to ask more informed questions, which can only improve the process of

deliberating a purchase offer.

We don’t expect

our study to put an end to the debate around fairness opinions. We do believe it

can help elevate that debate by injecting data where there has only been

conjecture, by replacing the anecdotal with the empirical and by better

equipping boards to make informed decisions.

Fairness Opinions 2006-2016

Most fairness

opinions use a robust set of methodologies to produce a useful range of

valuations, according to Duff & Phelps’ study of more than 3,000 publicly

disclosed fairness opinions.

Those conclusions

disprove periodic criticisms that fairness opinions generally provide little

utility for boards analyzing potential transactions. Specifically, some critics

have asserted that fairness analyses produce valuation ranges too wide to

provide meaningful information and that, because most fairness opinions are

based in part on DCF analysis, the opinions are too reliant on financial

projections that have been produced by management and left unscrutinized by the

fairness advisor.

We agree that

narrower valuation ranges are, intuitively, more useful to boards than wider

ranges. However, some deals are likely to produce wide ranges because the

companies themselves are difficult to value. The real question is whether wide

ranges are pervasive. And while we would also agree that relying solely on DCF

analysis (that uses projections company management has fed to the fairness

advisor) can be problematic, the follow-up should be to ask: is that really

happening?

In an effort to

answer those questions, assess the validity of periodic criticisms and determine

the overall usefulness of fairness opinions, Duff & Phelps conducted a thorough

analysis of more than 3,000 fairness opinions filed with the SEC during the

ten-year period ending in 2016. Specifically we looked at forms 14D and DEFM14A,

which companies are required to file when they are the target of a purchase

offer or require a shareholder vote.

A Valuable Tool for Boards

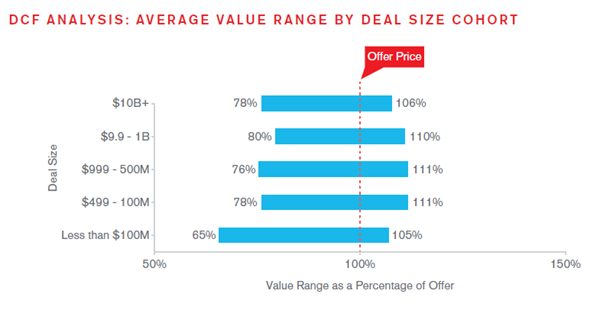

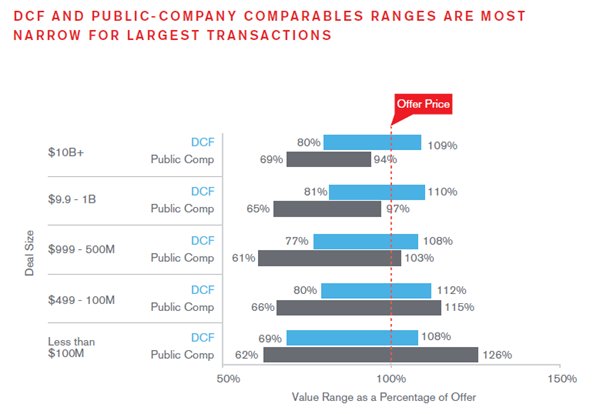

To test whether

wide ranges are pervasive, we analyzed publicly disclosed fairness analyses over

the last ten years. Our analysis confirms that on average, fairness opinions

deliver a range of valuations that is sufficiently narrow to serve as a valuable

tool in evaluating purchase offers. And the average range grows narrower as deal

size grows larger. Among deals we analyzed that carried a value of $10 billion

or more, DCF analyses produced average price ranges between 78 percent and 106

percent of the offer price. Large-cap companies typically are more diversified

and established, with more stable and predictable cash flows and broader

equity-analyst coverage. Armed with multiple, reliable sets of financial

projections and a variety of perspectives on the company’s future performance,

fairness opinion advisors can be expected to produce more precise valuation

ranges than when this information is absent.

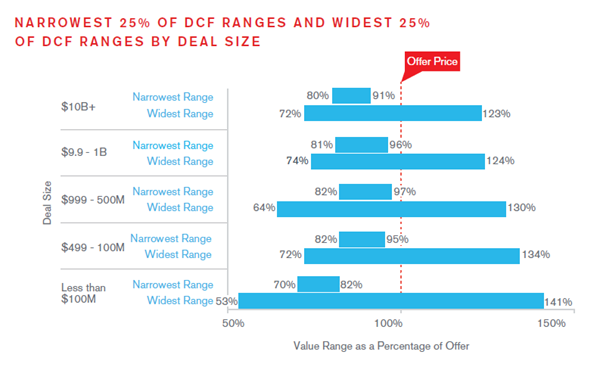

In the charts

above and below, valuation ranges are expressed as average percentages of the

implied share prices as compared to the offer price. The average range widened

only slightly for deals valued at less than $10 billion but more than $100

million. For deals valued at less than $100 million, DCF analyses produced

average price ranges between 65 percent and 105 percent of the offer prices. The

difference in average valuation ranges for micro-cap companies versus large-cap

companies is even more pronounced when we analyze the dispersion of fairness

opinion ranges. As the chart below illustrates, as company size decreases, the

widest 25% of valuation ranges increases.

Our

observation—wider and more disperse valuation ranges for smaller companies—is

not all that surprising. This reflects the heightened complexity involved in

valuing enterprises that are less mature, have less historical data to analyze

and compare, or are growing at a rate that causes dramatic variances in expected

cash flow.

In addition,

voluminous published analyses, including our own

Valuation Handbook—Guide to Cost of Capital,

[1] have shown that

discount rates decrease as company size increases due to the diminishing effects

of small-stock premiums. That research helps explain our finding that micro-cap

companies receive the broadest valuation ranges.

Methodologies: Rigor and

Sophistication Apparent

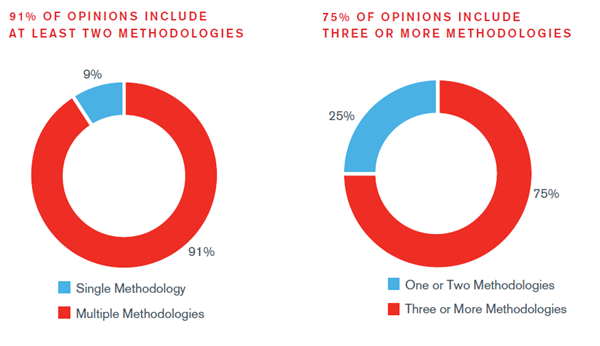

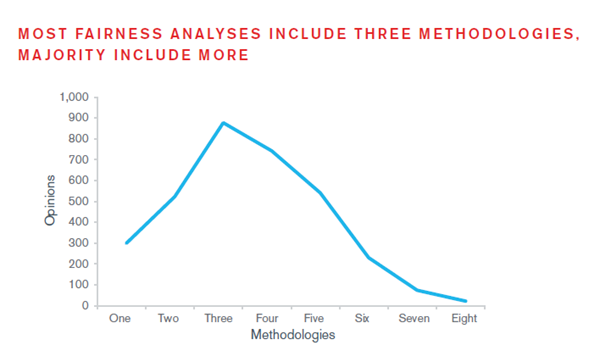

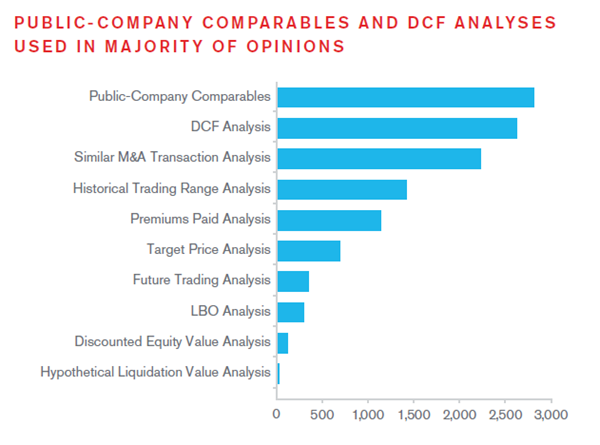

The findings

present clear signs of an industry standard at work among fairness opinion

advisors. Counter to the criticism that fairness opinions rely too heavily on

DCF analysis, we find that fairness advisors have been using multiple

methodologies for some time. For instance, 91 percent of the fairness opinions

we reviewed used more than one methodology to arrive at valuations. In 75

percent of the deals, advisors used three or more methodologies.

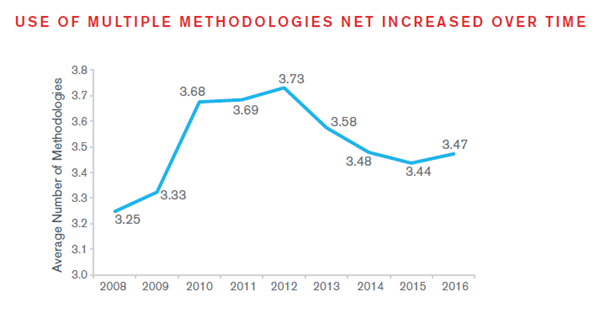

Moreover, we also

observed a slight increase in the average number of methodologies since 2008,

from an average of 3.3 methodologies to nearly 3.5 in 2016.

We argue that the

use of multiple valuation methodologies also significantly mitigates the

criticism that DCF analysis and therefore the opinion could be too heavily

influenced by unrealistic company projections. The common pairing of

public-company comparables and/or precedent transactions with DCF analyses,

often supplemented by one or more additional methodologies, demonstrates that,

in the vast majority of cases, fairness opinion advisors diligently consider

multiple perspectives and relevant analyses, when available, in assessing the

fairness of transaction prices. It also dispels the notion that fairness

advisors do not scrutinize management projections. Simply put, if the DCF

analysis produced a valuation range that bore little resemblance to a range of

values derived from other methodologies, that would be the first clue that

something might be amiss and thus warrants a closer look. After all, if the

public peer group or the set of precedent transactions is sufficiently

comparable, valuation multiples derived from these techniques can, in many

cases, provide an inherently more objective view of valuation.

Valuation Methodologies

Generally Congruent

To test our

assertion that a confirmatory valuation technique can serve as an effective

check on the DCF analysis, we also analyzed those fairness analyses that used

both DCF and public-company comparables. In the fairness opinions we reviewed,

DCF analysis usually provided the narrowest range of values. For deals valued at

below $10 billion, DCF analysis provided slightly narrower ranges of values than

public-company comparables analyses; for the largest of deals the ranges were

roughly equal.

In certain

circumstances, a significantly wider public-company comparables range may

indicate that a fairness opinion advisor overlooked a key step in that analysis.

In order to achieve a useful valuation based on public multiples, it’s crucial

that the advisor calibrate the selection of valuation multiples to those peers

with risk profiles and growth prospects similar to the subject company—to the

extent that such comparisons are sufficiently meaningful. Absent that

refinement, valuation ranges may be wider than necessary and in some cases

misleading. The data we collected showed that overall the public-company

comparables and DCF analyses produced relatively consistent ranges that were

reasonably narrow, particularly for larger companies where more information was

available. The consistency of the average valuation ranges across DCF and

public-company comparables analyses confirms the rigor and validity of both

methodologies. When done correctly, neither examination is mechanical and both

illuminate appropriate valuation ranges to boards and special committees.

Multiple DCF Scenarios

Indicate Additional Scrutiny

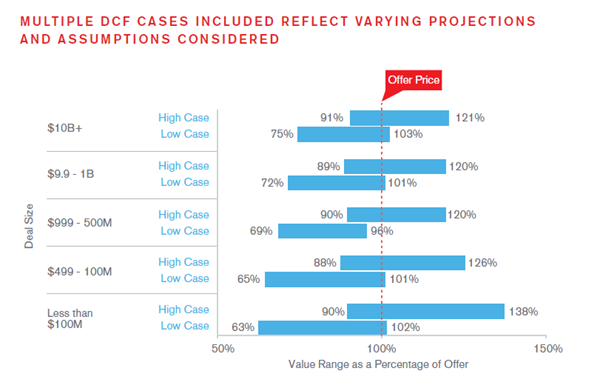

In 43 percent of

the filings we analyzed, fairness opinion advisors used multiple cases of DCF

analyses. This most likely indicates an attempt to account for multiple sets of

projections used for different purposes by management. One might reflect stretch

goals, for example, while another may have been produced to make the company

more attractive to buyers. Yet another forecast may use an amalgamation of

consensus projections from equity analysts to represent the market’s assessment

of the company’s prospects.

Most valuation

practitioners subscribe to the theory that DCF analysis should reflect the best

estimates available to management, without bias in either direction. The

frequent use of multiple DCF scenarios indicates that advisors are considering

every potentially pertinent projection, rather than simply accepting a single

set of forecasts. In addition, the presentation of two (or more) DCF scenarios

is likely the result of a growing judicial emphasis—via suggestion and

mandate—on disclosure. Companies today are less likely to pick and choose which

projections to disclose than they were a decade ago. Those who counsel boards of

directors may conclude that erroring on the side of complete disclosure—even if

a certain forecast included in regulatory filings was prepared for a much

different purpose than assessing fairness—is generally prudent for the filer.

Choice of Advisor Matters

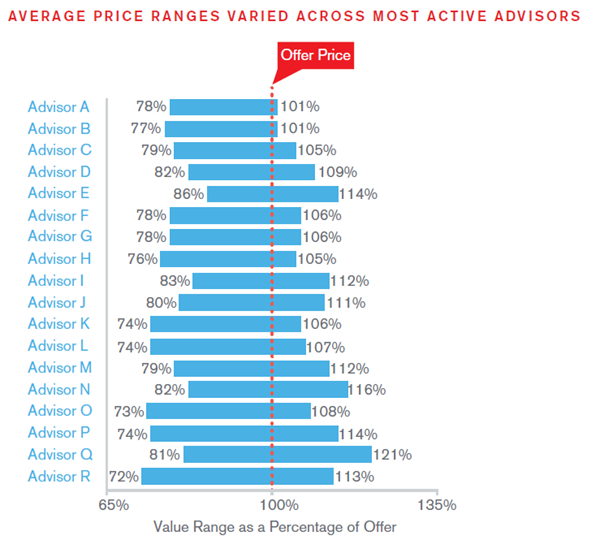

Finally, our

study reveals that valuation ranges vary by provider. Among the most active

advisors, the tightest average range, at 23 percentage points, is nearly twice

as narrow as the broadest range of 41 percentage points. This demonstrates that

the choice of an advisor does impact the precision and usefulness of a given

fairness opinion and illustrates the importance of following the best practices

described above—calibrating public-company comparables and scrutinizing

management’s projections.

Conclusion

Even as fairness

opinions have become standard practice, critics have questioned their efficacy

and usefulness. The criticism often surfaces in the wake of particular

transactions where there is public disagreement on the deal price or controversy

surrounding the fairness analysis, which generates widespread headlines. But our

analysis shows that those instances are outliers, typically owing to

peculiarities in circumstances more than to faults in the process.

The vast majority

of fairness opinions offer valuation indications that fall within 15 percentage

points on either side of a midpoint—a clear indication of a widespread industry

standard with robust methodologies and highly calibrated valuation analyses. For

the minority of fairness analyses that fall outside of this precise range, it’s

important to note that many of those outliers also may represent useful

valuation assessments. Not all companies fit neatly into valuation models and

not all deals are structured the same. When fairness opinions account for such

unique factors, we would expect them to produce price ranges that stray from the

average.

Our analysis

indicates that fairness opinion advisors use robust, sophisticated methods to

reach those valuations. From this we can only conclude that, broadly speaking,

fairness opinions represent a reliable way for corporate boards and executives

to evaluate purchase offers.

Methodology

This post relies

on data we collected from public filings available in the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission EDGAR database covering the timeframe January 1, 2006,

through September 30, 2016.

Valuation ranges

are expressed as average percentages of the implied share prices as compared to

the offer price.

EDGAR, the

Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system, allows collection,

validation, indexing, acceptance, and forwarding of submissions by companies and

others who are required by law to file forms with the SEC.

Data were

collected from the following forms:

SC 14D9

Solicitation

documents filed by the “being acquired” company regarding the offer it received.

SC 14D9/A

Amendment

documents filed after the date of filing original document (SC 14D9) that may

have amendments to the original content or new exhibits.

DEFM14A

“Definitive proxy

statement relating to merger or acquisition” as required under Section 14(a) of

the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

Endnotes

[1]

Available for

purchase at

www.duffandphelps.com/costofcapital

(go back)

|

Harvard Law School Forum

on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation

All copyright and trademarks in content on this site are owned by

their respective owners. Other content © 2017 The President and

Fellows of Harvard College. |