FORTUNE

Leadership

●

CEO Pay

CEO Pay May Soon Face a New, Hard-to-Manipulate Yardstick As ISS

Embraces 'EVA'

By

Shawn Tully March 28, 2019

U.S. companies—whether they like it or not—could

be on the verge of adopting a super-tough, super-fair new yardstick for C-suite

pay.

On Wednesday, ISS, the U.S.’s leading adviser on

corporate governance, announced that it’s starting to measure corporate

pay-for-performance plans using a metric that prevents CEOs from gaming the

system by gunning short-term profits, piling on debt, or bloating up via pricey

acquisitions to swell their long-term comp. ISS’s stance is a potential

game-changer: No tool is better suited to holding management accountable for

what really drives outsized returns to investors, generating hordes of new cash

from dollops of fresh capital.

The metric ISS champions is economic value added,

or EVA.

I wrote the first major piece on EVA in 1993, with

a Fortune cover story titled “The Real Key to Creating Wealth.” Roberto

Goizueta, the legendary

Coca-Cola chief who

rarely granted interviews, was such a fan that he invited me to Coke’s Atlanta

headquarters to educate our readers. “Call me Roberto!” declared Goizueta, who

downed serving after serving of espresso from a shot-glass sized paper cup.

“It’s like the bank robber Willie Sutton used to say,” he intoned. “EVA is where

the money is!”

The story caught the attention of the business

networks. A CNBC producer mistakenly pronounced EVA as a first name, and

mirthfully called the no-joke concept “Little Eva” after the woman who sang the

1962, Carole King-penned hit song “Do the Loco-Motion.” In the years that

followed, EVA didn’t exactly deliver on song’s line that “everybody’s dong a

brand new dance,” but it did find favor with a number of big companies. Among

the players that deploy EVA as a management tool are

Dow Chemical, Borg

Warner,

Deere & Co, and

Clorox.

What is EVA?

EVA is the best measure of what its advocates call

“economic earnings.” The tool is now owned by ISS, which publishes EVA analysis

of fifteen thousand global companies that it updates daily. The EVA methodology

makes two major adjustments to official GAAP numbers, or the ‘generally accepted

accounting principles’ adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission. First,

EVA imposes a “capital charge” on all the debt and equity used to make mobile

phones, semiconductors or autos. It deducts that charge from reported after-tax

operating profits, and the excess, or real profit to shareholders, is EVA. Under

EVA, a company may be showing what look like big earnings, but unless it’s

beating the cost of capital, it isn’t making money. In other words, an

enterprise only succeeds by exceeding the returns, or “opportunity cost,” that a

shareholder could garner in equally risky stocks and bonds. As Goizueta told me,

“I ‘pay’ my cost of capital and what’s left over I put in my pocket.”

Second, EVA makes several adjustments to GAAP

accounting to arrive at an adjusted earnings number (before the capital charge)

that better reflects whether operations are weak or robust. EVA, for example,

capitalizes R&D outlays as investments that should pay off in the future, and

expenses them over five years. It also applies a constant tax rate, based on

what the company pays on average, so that big swings in yearly levies don’t

artificially swell or depress earnings.

Current tools’ ‘shortcomings and blind spots’

ISS is the most powerful voice in advising

investors to vote up or down each year on pay-for-performance plans, as well as

board candidates and sundry initiatives that require shareholder approval. Until

now, it’s been deploying two criteria to evaluate` compensation: Total

shareholder return or TSR, and several traditional accounting measures. For ISS,

both have what it calls “shortcomings and blind spots.”

“Most companies’ executive pay plans cover three

years,” says John Roe, managing director of ISS. He notes that a company’s stock

price may rise to extremely high levels at the end of a pay period because

investors anticipate big profit gains over the coming years. Hence, top

executives can make extra millions not based on their returns on capital over

the past three years––which could be mediocre––but on expectations of what’s to

come. Market whims, not performance, could be unjustly rewarding CEOs.

“It’s like judging the climate by taking the

temperature on two separate days separated by three years,” says Bennett

Stewart, a Senior Adviser to ISS who pioneered EVA.

Besides TSR, ISS has been using several accounting

measures, including return on equity and EBITDA (earnings before interest,

depreciation and amortization). The rub is that reported results can be inflated

by adding leverage that lowers equity, and artificially boosts ROE. But adding

more debt simply makes the enterprise riskier by shrinking its margin for error,

so that in tough times investors will severely discount its stock price.

“Companies also will cut cash expenses such as R&D

and promotional spending to raise reported returns,” says Roe. “But those moves

weaken long-term performance.” EVA isn’t fooled by those maneuvers. Since it

spreads research spending over five years, and exacts a capital charge on the

amounts on the balance sheet, slashing one year’s budget does nothing to improve

economic profit. If a company is pouring in tons of capital by retaining

earnings and adding new borrowings, it can show growth in sales and profits, but

EVA will fall unless it delivers better-than-competitive market returns on all

that new capital.

A big acquisition may grow EBITDA, but destroy

shareholder value. The weakness of EBITDA is that it imposes no capital charge

at all. “It’s the world’s least accountable financial metric,” says Stewart. EVA

will expose whether the deal is a winner or a loser by applying the charge to

all the equity and debt used in the merger. The deal may add $1 billion to

reported earnings even after synergies, but if it cost $20 billion in equity and

at a 6.5% capital charge, EVA will be sharply negative. EVA provides a clear

dividing line between success and failure.

For this year, ISS will continue to evaluate

pay-for-performance using TSR and accounting measures. But for the first time,

it will also analyze comp using EVA. ISS will then gauge its clients’ reaction

to the new measure, and if it’s positive, as ISS expects, it will replace the

conventional ratios with EVA starting in 2020. ISS will continue to use TSR,

since it does measure how well the company is positioned for future growth,

according to the market’s current view. That’s forward looking. EVA, on the

other hand, fills in the rest of the puzzle by measuring the current results

that underpin TSR.

An EVA enthusiast

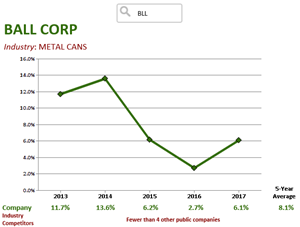

Among the biggest EVA enthusiasts is

Ball Corp, an $14

billion packaging manufacturer that was among the first to adopt the concept in

1991. Guided by EVA, Ball shed a number of low-return, capital intensive

businesses to focus on three highly profitable franchises: beverage cans, a

field where it’s world leader; satellites and antennas; and aerosol cans for

hairspray and the like.

“EVA gave us a disciplined approach in deciding

where to invest,” says Ball CFO Scott Morrison. All of Ball’s 8,000 non-union

employees are paid under bonus plans tied to EVA, on the same formula as the

CEO. “A plant manager can improve their EVA bonus by managing inventory better,

increasing profitability on a given amount of capital,” says Morrison.

Result: This old-line manufacturer has delivered

total returns of 382% over the last ten years, double the S&P 500 gains. As

Ball’s experience shows, EVA not only measures—and is the best way to pay

for—what really drives value, it shows managers how to get there. Going with EVA

is like joining the “loco-motion” chain that’s bound for glory.

© 2018 Fortune Media IP Limited. All Rights Reserved