THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

In News Industry, a Stark Divide

Between Haves and Have-Nots

Local newspapers are failing to make the digital transition larger

players did — and are in danger of vanishing

By

Keach Hagey, Lukas

I. Alpert and Yaryna

Serkez

Published May 4, 2019 at 12:00 a.m. ET

After suffering a historic meltdown a decade ago in the financial

crisis, American newspapers began racing to transform into digital

businesses, hoping that strategy would save them from the accelerating

decline of print.

The results

are in: A stark divide has emerged between a handful of national players that

have managed to stabilize their businesses and local outlets for which time is

running out, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of circulation,

advertising, financial and employment data.

Local papers

have suffered sharper declines in circulation than national outlets and greater

incursions into their online advertising businesses from tech giants such as

Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Facebook Inc. The data also shows that they are

having a much more difficult time converting readers into paying digital

customers.

The result has

been a parade of newspaper closures and large-scale layoffs. Nearly 1,800

newspapers closed between 2004 and 2018, leaving 200 counties with no newspaper

and roughly half the counties in the country with only one, according to a

University of North Carolina study.

Meanwhile,

about 400 online-only local news sites have sprung up to fill the void,

disproportionately clustered in big cities and affluent areas, the UNC study

found.

The shrinking

of the local news landscape is leaving Americans with less information about

what's happening close to them, a fact Facebook recently acknowledged as it

struggled to expand its local-news product but couldn’t find enough stories.

Local TV news is still a major, if declining, source of news for Americans, but

local newspapers are vanishing.

“It’s hard to

see a future where newspapers persist,” said Nicco Mele, director of the

Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, who predicts

that half of the surviving newspapers will be gone by 2021.

|

|

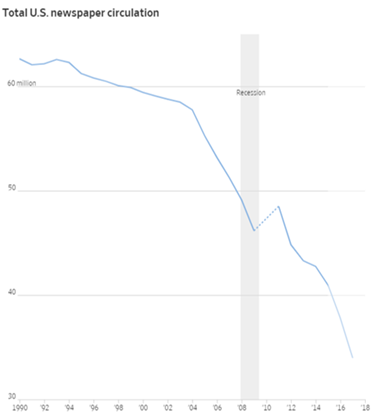

Declines

in print circulation intensified markedly after the recession, hitting

just about every industry player. |

|

|

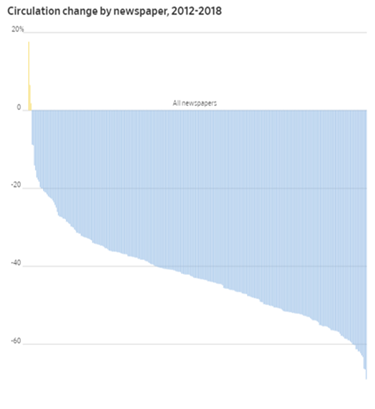

Of

almost 300 newspapers tracked by the Alliance for Audited Media for which

complete data is available, circulation fell for all but a handful between

2012 and 2018, a Wall Street Journal analysis of the data showed.

|

|

|

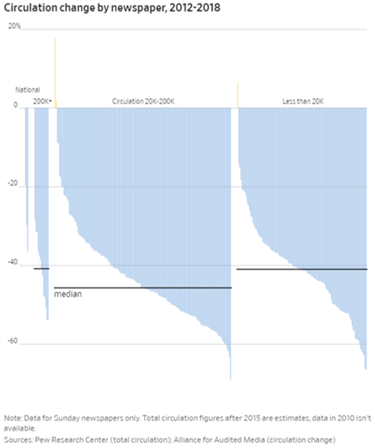

But the

pace of the declines varied. At three national papers, The Wall Street

Journal, the New York Times and the Washington Post, circulation dropped

an average of 29%. By comparison, the median drop at major metro papers

with circulation of more than 200,000, like Hearst’s Houston Chronicle and

Tribune Publishing Co.’s Chicago Tribune, was a steeper 41% over that time

frame. |

|

|

The pain

was even more pronounced among mid-sized papers with circulations between

100,000 and 200,000 —papers like Advance Publications Inc.’s Oregonian and

A.H. Belo Corp.’s Dallas Morning News, where circulation dropped some 45%

between 2012 and 2018. As print ads disappeared, the publishing cost of

maintaining a bigger circulation became untenable for many papers. Smaller

papers with circulation under 20,000 were actually somewhat better off,

with a median circulation drop of only 41%. |

THE ADVERTISING BLOODBATH

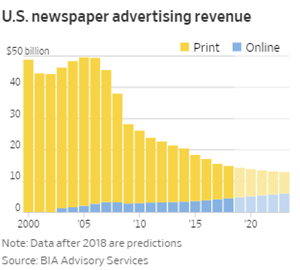

With print

advertising revenue hammered, online ad sales had seemed like the answer. But

online ads fetch a mere fraction of the price of print ads.

|

|

As a

result, digital ad sales didn’t come close to offsetting what was being lost

in print. |

Few people in

the industry understood just how potent Google and Facebook would become in

online advertising. By 2017, they accounted for 86% of all growth in the

industry that year, according to Brian Wieser, a former analyst at Pivotal

Research.

|

|

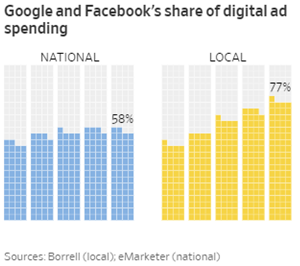

While

Google and Facebook have siphoned ad dollars away from all publishers, local

news publishers have been the hardest hit. The tech giants suck up 77% of

the digital advertising revenue in local markets, compared to 58% on a

national level, according to estimates from Borrell Associates and eMarketer. |

|

|

When you look at what’s evolved, and the amount of

revenue that’s going to the Googles and Facebooks of the world, we are

getting the crumbs off the table.

Alan Fisco, the

president of the Seattle Times |

|

Many local

newspaper companies tried to team up with the tech companies, creating “local

marketing services” units that heavily resell Google and Facebook ads. The

profit margins, however, are slim.

Terry Kroeger,

former publisher of the Omaha World-Herald and former CEO of its parent company,

Berkshire Hathaway’s media group, believes one solution is to allow publishers

to collectively negotiate with the tech platforms. He backs legislation that

would make that possible. A similar bill didn’t advance far in the last Congress

but Democrats are hopeful that the latest version, which has a Republican

co-sponsor, will gain momentum in the Democratic-controlled House.

“You can’t

help but admire Google’s business model,” Mr. Kroeger said. “They have close to

zero content-creation cost, but are able to turn around and sell the lion’s

share of the advertising.”

A LIFELINE IN DIGITAL SUBSCRIPTIONS?

Putting up a

digital-subscription paywall has so far only worked for a few.

|

|

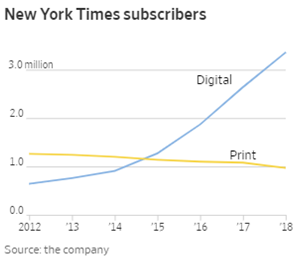

Three

large national papers have had some success, attracting more subscribers to

their digital product than their print paper. |

For many

years, News Corp’s Wall Street Journal was alone among major newspapers in

requiring readers to pay for articles online, a decision it made in 1996. In

2011, New York Times Co. followed suit.

Today the

Times boasts 3.4 million digital subscribers—2.7 million of whom are paying for

the news product, with the rest springing for crosswords and cooking extras—and

a newsroom of 1,550 journalists, the largest in its history. The Journal has 1.7

million digital subscribers and a newsroom of nearly 1,300.

The Washington

Post, which launched a paywall in 2013, has transformed under the ownership of

Jeff Bezos into a national digital enterprise, amassing 1.5 million digital

subscribers, according to people familiar with its operations.

All three

newspapers have their own challenges and are far from out of the woods. But they

have all managed to increase revenue with the help of digital subscriptions,

bucking the trend at their local counterparts. The Times charges $15 for a basic

monthly subscription, the Post, $10, and the Journal, $39.

|

|

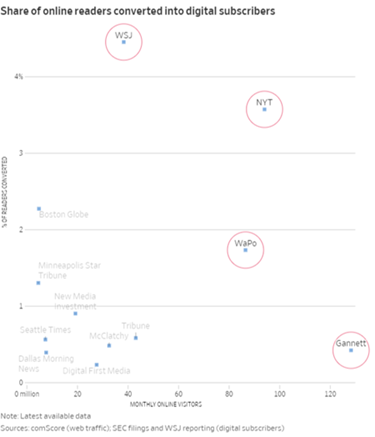

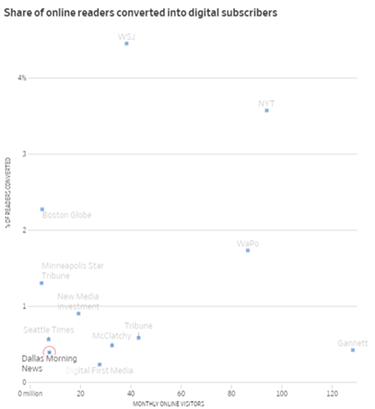

Those

bigger outlets have been much more efficient at converting online readers

into paying digital subscribers than local publishers. The Times converts

3.6% of its readers and the Journal 4.5%, while Gannett, which has a big

audience across its local papers, is especially inefficient, converting

just 0.4% of its digital audience into paying subscribers, according to

the Journal’s analysis of digital audience and subscription data. Many

paywalled sites allow casual users to sample some content for free. |

|

|

Gannett says that excluding USA Today, its largest source

of web traffic, and other papers that do not have paywalls, its conversion

rate would be 1.4%. |

|

|

The Dallas Morning News in 2011 became the first major

regional U.S. outlet to make readers pay for news online. The paper, which

relaunched its paywall in mid-2016 after two previous attempts, now counts

around 30,000 digital subscribers, according to people familiar with the

matter, but that contributed only 5.6% of its total circulation revenue in

2018. In the past 15 months, the paper has cut more than 170 employees. A

major investor is now urging the company to consider a sale. |

|

|

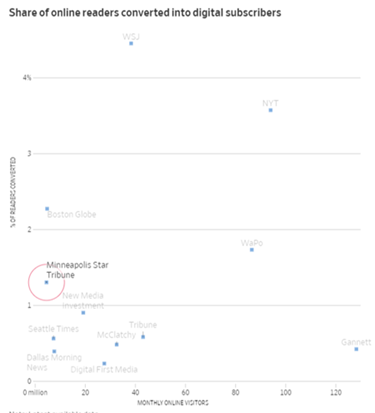

The

Minneapolis Star Tribune, owned by billionaire Glen Taylor, has signed up

60,000 digital-only subscribers, and takes in around $200 million in

revenue annually, which has allowed it to maintain a newsroom of around

250 for the better part of a decade. “We have stayed profitable, but it

gets tighter every year,” said Michael Klingensmith, the paper’s publisher

and chief executive. The Star Tribune will need to surpass 150,000 digital

subscribers to be sustainable in the longer term, he said. |

|

|

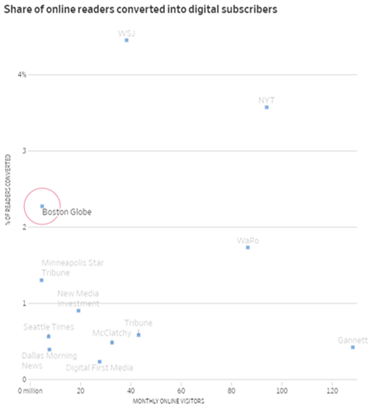

A

notable outlier is the Boston Globe, which has amassed 111,000

digital-only subscribers at the robust price of $1 a day, allowing it to

support its newsroom of 200 journalists on digital subscription revenue

alone. Globe President Vinay Mehra says the paper’s focus on investigative

reporting and sports under Boston Red Sox owner John Henry, who bought the

paper in 2013, has propelled its success. Some 35% of those digital

subscribers are from beyond New England, a testament to the popularity of

the Red Sox and New England Patriots—a luxury few papers have. |

|

|

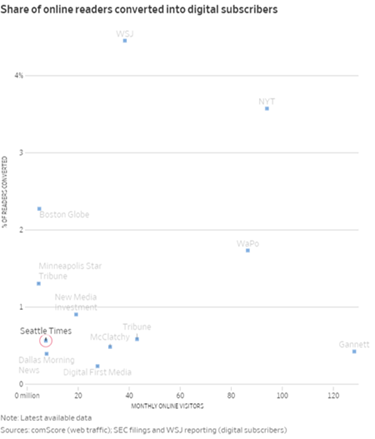

The

Seattle Times, which has been locally owned for 122 years, has racked up

42,000 digital-only subscribers since launching its paywall in 2013, the

company's president, Alan Fisco, said. But, he added, it is still far from

the 100,000 digital-only subscribers it needs to be able to fund its

newsroom of 150. |

Peter Barbey,

publisher of the Reading Eagle, thought he did everything right according to the

industry’s digital growth playbook. When the heir to the multibillion dollar

fortune behind brands like The North Face and Timberland took over his family’s

Pennsylvania newspaper in 2011, he quickly put up an online subscription paywall.

He also grew web traffic, embraced social media to promote stories and built up

a digital ad sales team — all now considered vital components of any newspaper’s

digital turnaround strategy. All the while he built up a high-quality newsroom

that won awards.

It wasn’t

enough. The Reading Eagle signed up only 3,000 subscribers, not enough to make a

difference with online ad sales hitting the Google-Facebook wall and print

revenue falling roughly 25% in just the past two years.

In March, the

paper Mr. Barbey's family has owned since 1868 filed for bankruptcy. "It’s like

we were in a canoe paddling upstream and there was a waterfall behind us," Mr.

Barbey said.

Warren

Buffett’s U-turn on newspapers is an indicator of the industry’s predicament.

The legendary investor began buying up local papers in 2011, betting they could

overcome the horrible economics of the print business by making a transition to

the internet.

They didn’t.

Last year the “Oracle of Omaha” turned over management of his papers to another

company, Lee Enterprises. He recently told Yahoo Finance that newspapers were

"toast," adding that, with the exception of the three biggest national papers,

"they are going to disappear."

Executives at

some outlets, such as the Omaha World-Herald, talked about paywalls for years,

but didn’t truly get serious about them until recently, by which point staff

cutbacks had made it hard to put out a product people would pay for. Mr.

Buffett, whose company purchased the paper, told the Journal that the

World-Herald’s digital product had “grown significantly in the past year,” but

“remains well short of where it needs to be.”

A SHRINKING INDUSTRY

For years,

many in the news industry believed that even if newspapers vanished, journalism

would flourish in a lower-cost, digitally native form. But those hopes proved

misplaced. .

|

|

Newspaper

jobs declined by 60% from 465,000 employees to 183,000 employees between

1990 and 2016, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since January,

more than 1,000 newspaper jobs have disappeared through layoffs and buyouts. |

Jobs in the

Bureau of Labor Statistics’s internet publishing and broadcasting category, the

best measure of online news employment available, rose from 29,000 to 197,800

during the same period. Those jobs have been highly concentrated in New York and

California, according to a Journal analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

That would

leave large swaths of America with radically diminished access to local news. A

future without newspapers, Mr. Mele of the Shorenstein Center, says, is

“actually a crisis for democracy.”

At many

outlets, no amount of job cuts could save them. Openings of online-only news

sites haven’t made up for flood of newspaper closures. The result is that rural

areas and poor neighborhoods are fast becoming news deserts.

|

|

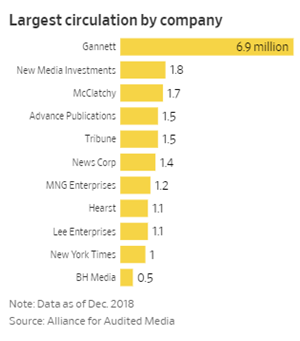

Newspapers’ financial woes have spurred consolidation. Financial investors

such as hedge fund Alden Capital, backer of MNG Enterprises, and private

equity firm Fortress Investment Group, operator of Gatehouse Media, are

now formidable players and are pushing for ever-deeper cost cuts. MNG,

which was formerly known as Digital First Media, is pursuing a hostile

takeover of Gannett Co., the largest newspaper chain by circulation. MNG

is skeptical of newspapers investing heavily in digital strategies,

pointing to Gannett’s $350 million in digital acquisitions as a strategic

disaster. |

MNG, which

owns the Denver Post and San Jose Mercury News, says “the newspaper business is

in secular decline,” arguing the better strategy is to focus on profits now.

“What Alden is

doing is liquidating,” said Dean Singleton, who founded the company that now

forms the crux of MNG Enterprises and pioneered several newspaper cost-cutting

measures, but who is no longer associated with the company. “They are taking the

cash out as quickly as they can and reinvesting in businesses they think have

more promise. It may be a very good business strategy, but it is not a good

newspaper strategy.

MNG says its

aim is to make newspapers sustainable, not close them.

PROPPING UP NEWS

As local

journalism’s business model foundered, many in the industry began to believe

that it could only be rescued through charity or outside support.

Google and

Facebook have each announced $300 million commitments to help strengthen

journalism, including funds earmarked for local news, and Craigslist founder

Craig Newmark has given more than $85 million to journalistic causes.

|

|

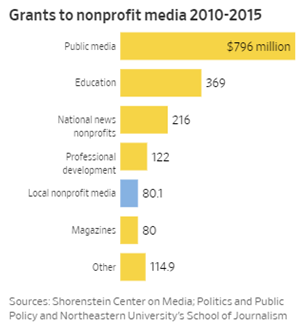

Between

2010 and 2015, foundations gave $80.1 million in grants to local and state

nonprofit news organizations, according to a study by the Shorenstein Center

and Northeastern University. That amounts to just 5% of the total that

foundations gave to media, and less than one one-hundredth of the $8.3

billion in revenue that newspapers lost during that time, according to the

study and a Journal analysis of Pew data. |

At the moment,

national institutions like the Knight Foundation are the largest source of

funding for local nonprofit journalism.

|

There has been a very significant outpouring of

national support for local journalism, philanthropically, in the last

year or two, but there has been very little local support for local

journalism.

Richard Tofel, president of the nonprofit journalism outlet ProPublica |

In part that

may be because local journalism’s financial woes are not widely known. A recent

Pew study found that 71% of Americans believed local news outlets were doing

well financially, though only 14% actually paid for local news.

Jim Friedlich,

the chief executive of the Lenfest Institute for Journalism, which owns the

Philadelphia Inquirer and supports local journalism initiatives, said the

nonprofit organization has worked hard to attract financial backing beyond gifts

from local billionaire H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest.

The institute

has raised more than $20 million more from other donors by positioning news as a

civic need.

“There is no

reason why other communities can’t follow suit,” Mr. Friedlich said. “Indeed,

they are.”

Illustration by Doug

Chayka.