The Board’s Impact on Long-term Value

Posted by Shawn Cooper (Russell Reynolds

Associates) and Sarah Keohane Williamson (FCLTGlobal), on Thursday,

June 25, 2020

Taking a

long-term approach in business leads to superior performance.

Companies that

orient themselves around a long-term time horizon while also delivering against

short-term objectives have been shown to outperform their peers on several key

business measures, including revenue, earnings, economic profit, market

capitalization and job creation. These companies were hit hard during the last

major economic downturn—as were most businesses—but saw a higher-than-average

rebound after markets recovered.

According to one

economic analysis, had short-term-oriented companies behaved more like

long-term-oriented ones, the global economy would have created an additional

$1.5 trillion in returns on invested capital in the years following the Great

Recession. [1]

|

What Is “Long-Termism”?

It is how

boards and executives think and act in regard to the practice of applying

a long-term approach to business and investment decision-making, including

focusing on key elements of performance such as competitive advantage,

long-term objectives and a strategic plan matched with clear capital

allocation priorities. It stands in contrast to short-termism, or a

continued focus on quarterly or other near-term performance issues, and is

increasingly in demand from stakeholders who want a fundamental rethink

around how companies operate and create value. |

While the benefit

of long-termism is clear, the path to getting there is not. By all accounts, and

for a variety of reasons, taking a long-term orientation in business can be

difficult, especially for executives. But if the board of directors is committed

to taking the long-view, there are a number of specific steps to they can take

to get there, beginning with asking a key set of questions:.

-

As a board, are

we satisfied with our company’s performance?

-

Is the company

being fully valued in the market?

-

Is the board

playing an appropriate role in creating shareholder value?

Market valuation

is a combination of two things: short-term performance and long-term potential.

When executives over focus on one of the two—and directors don’t correct

course—a company risks becoming either a flash in the pan, or a dreamer that

fails to survive long enough to realize its vision. To avoid either fate, boards

need to find the right balance between short-term and long-term issues, partner

with executives to ensure the company is managed the same way, and engage with

the market to build support for their vision and goals. It is no easy task.

Despite these

challenges, there are companies that align around a long-term time horizon that

successfully oriented themselves this way. In these companies, management and

the board share an explicit set of behaviors that focus themselves—and often the

investors too—on the long term. How did this happen? And what differentiates

those boards of directors that have been the most successful at focusing their

company on the long term from those that have not?

There is

a clear divide between companies that align for the long term and those that do

not

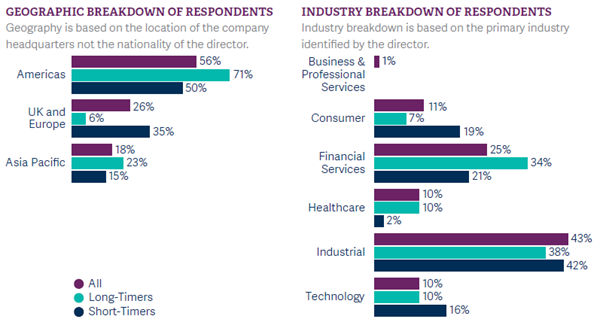

In late 2019,

Russell Reynolds Associates and FCLTGlobal (Focusing Capital on the Long Term)

launched an extensive research effort to understand how corporate directors

consider time horizons in their work; how the topic is discussed in the

boardroom, facilitating alignment between and among management and the board and

investors; and how a long-term orientation influenced director recruitment,

assessment and selection. This research included an in-depth global survey of

163 corporate directors. Respondents hailed from all major industry segments and

all corners of the world: Fifty-six percent of respondents were at companies

headquartered in the Americas, 26 percent in Europe (including the United

Kingdom), and 18 percent in the Asia Pacific region.

The remaining

directors served on a board where directors and management were not aligned on

their time horizon focus (i.e., management was long-term oriented, while

directors were short-term oriented, or vice versa).

It is worth

noting, of course, that different industries are influenced by different market

forces, some of which naturally result in a bias toward being more short-term or

long-term oriented. The data highlighted in this report is for all respondents,

and all industries, combined. See Appendix for a breakout of results by

geography and industry and a brief discussion of differences between and within

certain industries.

While the two

groups were identified based solely on their primary time horizons, as we

analyzed their responses, we saw significant differences between short-termers

and long-termers on almost 30 factors measured in the study—from why they

decided to be board directors in the first place through to how they conduct

themselves in the boardroom.

There is a stark

contrast in motivation to board service between short-termers and long-termers.

Long-termers are more likely to identify a primary motivation that is

company-focused or altruistic in nature, such as providing skills and experience

to help the company succeed, being interested in the nature of the company or

industry or believing in the purpose or mission of this specific company.

Short-termers, by

contrast, overwhelmingly indicated that their motivation to serve was about

benefiting themselves. They were more likely to say they were motivated out of a

desire for exposure to an interesting and challenging role, enhanced career

development and experience, improved personal brand and business reputation,

financial compensation for board service, or building a broader business

network. In fact, not a single long-termer identified either of those last two

reasons as a motivation for their board work.

No board

intentionally goes in search of short-termer director candidates, but we found a

higher prevalence of them than we would have expected to. It is a reminder that

boards need to stay vigilant when identifying and assessing director candidates,

and on addressing bad behaviors when they show up in the boardroom. For more

guidance on this, see “From Insight to Action” below.

Today Versus

Tomorrow

Once on the

board, long-termers and short-termers act differently. They report focusing on

different issues, discussing different topics and keeping an eye on different

trends and metrics.

When it comes to

identifying the most significant threats to the company’s performance, short-termers

focus on issues in the here and now, like failure to execute and operate the

business efficiently and failure to respond to changing customer preferences.

There are times when every organization should focus on these issues, but short-termers

appear to stay fixated on them beyond the point where a transition to other

topics would create longer-term value.

By contrast,

long-termers oriented around concerns that are more likely to play out over

years or decades. They identified regulatory uncertainty, macroeconomic

uncertainty and a failure to realize a return on innovation investments as their

top areas of worry.

|

Table Stakes: What Every Board

Has on the Agenda

Both groups

shared a common understanding of the top three drivers that were important

to the company’s strategy and success: innovating to produce new products

or services, reducing cost or improving efficiency, and innovating to

improve existing products or services. Given the shared focus on these

issues, it seems fair to consider them table stakes for corporate boards.

They are also likely topics where board leadership can focus discussion to

create alignment among directors given the shared appreciation of their

importance to the company. Interestingly, however, the two groups diverged

significantly on what the next most important drivers were. |

Short-termers

were highly focused on issues related to delivering immediate results:

increasing profitability, improving existing customer perceptions and

satisfaction and increasing revenues. In contrast, long-termers were all about

growing and expanding the business: increasing market share, expanding into new

markets and growing through acquisition. Again, we see a continuation of the

theme of short-termers focusing on the present and long-termers focusing on the

future.

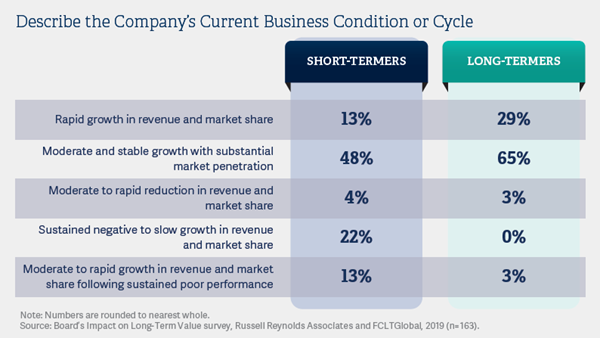

While it is

certainly true that companies which are in free fall, or which are facing doubt

about their ability to survive, should be more focused on the immediate than the

future, it would be wrong to assume that the short-termers in this study are all

facing those challenges. In fact, 61 percent of short-termers reported that

their business was in a period rapid growth in revenue or market share (13

percent) or in a period of moderate and stable growth with substantial market

penetration (48 percent). Another 13 percent reported moderate to rapid growth

in revenue and market share following a period of sustained poor performance.

These directors are not standing on burning platforms.

Not only do long-termers

and short-termers report focusing on different topics during board meetings, but

they also report that their board meetings operate differently from each other.

Long-termers report that their board meetings are more organized and better

structured relative to short-termers, that their fellow directors have a

stronger grasp of organizational culture and talent issues and that their peers

also have a greater level of expertise about the broader industry.

Beyond

Business Acumen

One area where

both groups are united? Long-termers and short-termers both say that their

fellow directors rate high on business acumen (the scores between the two groups

are separated by only one percentage point). It isn’t that one group is

recruiting high-performing and capable directors and the other is not. But there

is ample evidence that long-termers are more likely to dig in to better

understand the business and industry and to come to meetings better prepared and

more likely to focus on the work at hand. They are applying their skills and

time differently.

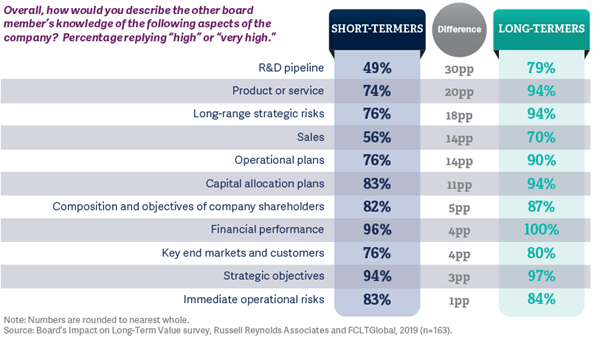

Around the

boardroom table, long-termers report being significantly better informed about

the company, strategy and operations—outperforming short-termers in every single

area.

Remarkably, long-termers

aren’t just better informed about long-term topics relative to short-termers,

but they are also better informed about short-term ones. Long-termers are

significantly stronger on issues related to current products and services, sales

activities, operational plans, financial performance, and immediate operational

risks. It is clear that long-termers understand something critical: A long-term

orientation isn’t undertaken in lieu of short-term focus, but in addition to it.

We see similar

results when asking short-termers and long-termers to rate the performance of

their fellow directors on behavioral issues: In every single case, long-termers

dramatically outperform short-termers.

From Insight

to Action

It is clear that

the way the board is led, and how it uses its time, matters. Long-termers report

that their board meetings are highly organized and structured, resulting in a

strong board culture focused on long-term growth and performance. What can board

leaders do to create an environment like that?

Previous

research outlines seven specific activities directors and board leaders can take

to have a positive impact on boardroom culture:

[2]

-

The chair needs

to purposefully foster and facilitate high-quality debates around the

boardroom table

-

In the course

of the board’s deliberations, the chair should intentionally draw out the

relevant expertise of the independent directors

-

All directors

need to keep the discussion focused on the matter at hand and eliminate

tangents during meetings

-

Starting with

the onboarding process and continuing throughout their tenure, directors

should build and demonstrate trust through their words and actions with their

fellow directors

-

The board must

be careful to avoid crossing the line from oversight into operations or

management

-

Everyone in the

boardroom must be open to new ideas and ways of doing things

-

Lastly,

directors should remain willing to constructively challenge management when it

is appropriate to do so

In addition to a

willingness to challenge management, there is a need for open and honest

communication between the board and management so management is clear about

their board’s goals and desires for the company. Directors may desire a

long-term orientation for the organization, but if they don’t guide and

incentivize executives to take the same view, they’ll never get alignment

between the board and management. A well-functioning corporate board of

directors—one that is aligned on time horizons and communicates clearly with

management—wields the power to meaningfully influence the purpose, culture and

direction of the organization. There are many ways they can do so,

[3] including:

-

Like long-termers,

focusing on both the long term and the short term in their board work. But it

can be easy to create the mistaken impression of being overly focused on

short-term issues by the way directors engage with executives in the

boardroom. Directors need to be clear that while they are asking about both

time horizons, their primary interest is on the long term. Board agendas

should be crafted to include agenda items that are focused solely on long-term

issues, and to frame short-term issues relative to their impact on long-term

strategy. Directors may also wish to regularly review past agendas as one

indicator of if they are focusing on long-term issues as much as they think

they are. [4]

-

Providing

explicit guidance to management to be long-term While it may sound simple, it

is critical for the board to explicitly communicate to executive and other

employees that the board desires a long-term orientation. This doesn’t have to

be complex—it can simply be a series of ongoing statements that occur during

the natural course of doing business. Repetition of the message will help it

become part of the culture over time.

-

At the same

time, making sure directors are not sending mixed messages to executives via

other If a board is explicitly focused on the long term, but something like

executive compensation is based on short-term performance measures, executives

will naturally be conflicted. Executive compensation should be explicitly

linked to long-term value creation, and the board should examine all of the

key performance criteria and metrics to ensure they are not inadvertently

incentivizing management to focus on the wrong thing.

-

Aligning

compensation to long-term value creation for the board, not just CEOs and

other senior executives aren’t the only ones who should have their

compensation tied to long-term value creation. Companies should compensate

board members primarily in stock and consider locking up their stock awards

through or beyond their terms of service.

-

Developing a

board statement of purpose that emphasizes long-term Amazon is perhaps the

most well-known example of this, saying, “The board of directors is

responsible for the control and direction of the company…. The board’s primary

purpose is to build long-term shareowner value.”

[5] A statement of purpose like this

makes clear the role of the board and the importance of embracing a long-term

orientation, and it sends a clear message to investors about how the board

approaches its job.

It takes a

village to create a long-term-oriented organization. While this study focused

primarily on the board and management, it is also critical to establish early,

frequent and open engagement with external stakeholders, including majority

shareholders. They need to understand the intent, strategy and approach to

creating a long-term organization. Perhaps most importantly to them, they need

to understand the investment required and the anticipated payoff of taking this

approach. Unless investors are persuaded, it’s likely the board will lose their

support, and it may also face increased investor activism.

Lastly, building

a long-term-oriented organization requires getting the right directors into the

boardroom. Based on this research, it is important for nominating and governance

committee chairs to understand how director candidates think and then seek to:

Establish an

Evergreen Board Recruitment Process:

Many boards move

from director search to director search, treating succession planning and

director recruitment as transactional processes. Switching to an evergreen

process, where boards start to identify pools of potential director candidates

months if not years in advance of when they are needed, allows for boards to

thoughtfully identify and vet candidates with the right motivations, mindset and

approach.

Understand

Candidate Motivations:

Directors are

motivated to board service for a variety of reasons. Look for candidates who

talk about service-oriented motivations (providing skills and experiences to

help the company succeed, exposure to an interesting and challenging role,

interest in the nature of the company or industry, belief in the purpose or

mission of the specific organization) rather than motivations that focus on

benefiting themselves (enhanced career development and experience, improved

personal brand and business reputation, financial compensation for board

service, building a broader business network). Remember to continue to probe on

past experiences to get beyond cursory answers and understand how director

candidates truly think.

Ask Candidates to

Discuss Their Current Company’s Strengths and Threats:

Long-termers and

short-termers focus on very different things when talking about their company.

When talking about threats, look for candidates who focus on more macro or

long-term issues (regulatory uncertainty, macroeconomic uncertainty, failure to

realize a return on innovation investments) as opposed to day-to-day issues

(failure to execute and operate the business effectively, failure to respond to

changing customer preferences). Similarly, look for a discussion of strengths

that is focused on growth and expansion (increasing market share, expanding into

new markets) rather than incremental changes (increasing profitability,

improving customer perceptions and satisfaction). When doing so, remember to

take into consideration broader circumstances: If the company was in a

turnaround, it’s both reasonable and expected for the board to be focused on

shorter-term issues, but not so much when the company is in a period of

prolonged growth and success.

Thoughtfully

Onboard New Directors:

A solid

onboarding for new directors sets them up for success. It also proves a method

through which to help new directors understand the board’s perspective on

business issues, including their long-term orientation. To maximize the impact

of the onboarding process, ensure it is both well designed and thoughtfully

executed. [6]

Remember that new directors often have very different backgrounds from current

directors due to a desire to bring in leaders with different skills and

experiences, and these directors may well need an onboarding that emphasizes

topics and issues than weren’t covered for previous directors.

For most boards

of directors, there is a large gap between their current way of operating and

being able to honestly say that their primary purpose is to “build long-term

shareowner value.” But the benefits of doing so—to the board, management, the

company and shareholders—are overwhelming, and the way to do so is clear.

|

A Checklist

for Directors

It is clear

that the way the board is led, and how it uses its time, matters. Long-termers

report that their board meetings are highly organized and structured,

resulting in a strong board culture focused on long-term growth and

performance. What can board leaders do to create an environment like that?

-

Purposefully foster and facilitate high-quality debates

-

Intentionally draw out the relevant expertise

-

Keep the

discussion focused on the matter at hand and eliminate tangents

-

Build and

demonstrate trust through their words and actions

-

Avoid

crossing the line from oversight into operations or management

-

Be open

to new ideas and ways of doing things

-

Constructively challenge management when it is appropriate to do so

A

well-functioning corporate board of directors—one that is aligned on time

horizons and communicates clearly with management—wields the power to

meaningfully influence the purpose, culture and direction of the

organization.

-

Use clear

language during discussions to emphasize that the primary focus is on

the long

term

-

Craft

boards agendas to include items that are focused on long-term issues

-

Regularly

review past agendas and meeting minutes to confirm time is being spent

as

intended

-

Provide

explicit guidance to management to be long-term oriented

-

Ensure

directors are not sending mixed messages to executives via other means

-

Explicitly link executive compensation to long-term value creation

-

Examine

all of the key performance criteria and metrics to ensure they do not

inadvertently

encourage a focus on the short term

-

Align

compensation to long-term value creation for the board, not just

management

-

Compensate board members primarily in stock and consider locking up

stock awards through

or beyond the term of service

-

Develop a

board statement of purpose that emphasizes long-term interests

It is

critical to establish early, frequent and open engagement with external

stakeholders.

-

Communicate intent, strategy and approach

-

Explain

the investment required and the anticipated payoff of taking a long-term

approach

Lastly,

building a long-term-oriented organization requires getting the right

directors into the boardroom. Based on this research, it is important for

nominating and governance committee chairs to understand how director

candidates think and then seek to:

-

Establish

an evergreen board recruitment process

-

Ask

candidates to discuss their current company’s strengths and threats

-

Understand candidate motivations

-

Thoughtfully onboard new directors

|

Appendix

Geographic

and Industry Breakdown of the Data

Consumer includes

leisure and hospitality, media and entertainment, retail, and consumer products.

Healthcare includes medical devices, pharmaceuticals and healthcare services.

Industrial includes automotive; chemicals, materials and packaging; energy and

natural resources; industrial goods; and industrial services. Technology

includes hardware, software, services and telecommunications.

Four differences

emerge from the industry breakdown of data:

Consumer

has an elevated percentage of directors who indicated that they and the company

are short-termers. This difference is driven mainly by directors from retail

companies, who naturally are more impacted by short-term changes in the market

and in consumer preferences.

Financial

services

has an elevated percentage of directors who indicated that they and the company

are long-termers. This difference is driven mainly by directors from banking and

insurance companies, who often must ride out short-term disruptions in the

market and measure their success over longer periods of time.

Healthcare

has a very small percentage of directors who indicated that they and the company

are short-termers. This difference is driven mainly by directors from

pharmaceuticals, who deal with multibillion-dollar investments and decades-long

time horizons for drug development.

Technology

has an elevated percentage of directors who indicated that they and the company

are short-termers. This difference is driven mainly by directors from technology

hardware businesses, who, like retailers, are naturally more impacted by

short-term changes in the market and in consumer preferences.

Endnotes

1

McKinsey & Company, “The Data: Where Long-Termism Pays Off,” Harvard Business

Review, May–June FCLTGlobal, “Predicting Long-Term Success for Corporations

and Investors Worldwide.”

(go back)

2 Russell Reynolds Associates, “Going for Gold:

The 2019 Global Board Culture and Director Behaviors Survey.”

(go back)

3 FCLTGlobal, “Is My Board Cultivating the Long-Term

Habits of a Highly Effective Corporate Board?”

(go back)

4 FCLTGlobal, “Time Visualization Meter.”

(go back)

5 Amazon.com, “Guidelines on Significant Corporate

Governance Issues.”

(go back)

6 Russell Reynolds Associates, “Enhancing New

Director Performance and Impact.”

(go back)

|

Harvard Law School Forum

on Corporate Governance

All copyright and trademarks in content on this site are owned by

their respective owners. Other content © 2020 The President and

Fellows of Harvard College. |