|

Government |

Securities Enforcement |

Compensation |

Shareholder Activism |

Corporate Structure

Vote no to bashing proxy advisers

By John

Foley

April 26, 2024 8:00 AM EDT

Commentary

By John Foley

NEW YORK, April 25 (Reuters Breakingviews)

- Jamie Dimon is a busy man. Yet the JPMorgan (JPM.N) boss

found time to devote more than a page of his annual

letter to

shareholders this year to his disdain for two small companies:

Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis. These shareholder

advisory firms, tiny compared to the $550 billion U.S. bank Dimon

runs, punch above their weight in influencing how companies and

investors behave. Their impact is problematic, but they are not the

problem.

Fund managers have a duty to vote when shareholder meetings roll

around each spring, but evaluating every motion at every company would

require an enormous amount of time and effort. That’s where proxy

advisers come in. ISS and Glass Lewis pore through thousands of

companies’ public filings on topics like pay, governance and

sustainability, and publish recommendations for each item on the

ballot. For most votes, like reappointing auditors or re-electing

directors, there’s little controversy. When contested issues pop up,

so does attention to what proxy firms say.

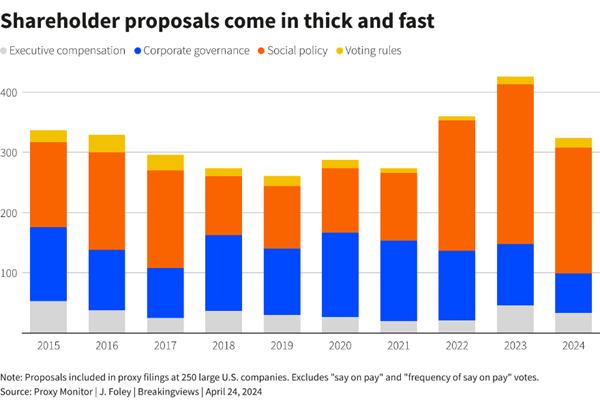

Reuters Graphic

Executive pay and activist investors are classic flashpoints. Proxy

firms dig into the alignment between top managers’ compensation, their

performance, and broader principles in a way equity analysts generally

do not. And when a dissident shareholder nominates its own directors

to a company’s board, proxy advisers will opine on whether other

investors should concur. The two main firms don’t always agree: When

Nelson

Peltz’s Trian Management recently tried to win a seat on Walt

Disney’s (DIS.N), board, ISS backed

him and Glass Lewis did not. In the end, Disney shareholders sent

Peltz packing.

Nobody is forced to use ISS, Glass Lewis or any proxy adviser. But

Dimon, like some of his peers, cannot abide their role. JPMorgan’s

long-serving CEO argues that the firms have “undue influence”, and

that they provide information that is “not balanced” and “not

accurate.” He even warns that Glass Lewis and ISS are owned by

non-American investors, a complaint that jars with the Wall Street

veteran’s otherwise globalist leanings. Germany’s Deutsche Boerse (DB1Gn.DE)

bought ISS in 2021. Glass Lewis is owned by Canadian investors.

Dimon’s

anger isn’t surprising, because the proxy advisers’ views directly

affect him and his counterparts. Shareholders in American companies

are becoming more active in submitting proposals for annual meetings.

Many address topics such as lobbying and climate goals only indirectly

related to maximizing near-term profit. The U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission, which can shield companies from investor

micromanagement, is letting more motions through.

One issue that keeps coming up is the

question of whether CEOs like Dimon have too much power. On May 21,

JPMorgan shareholders will vote on whether to split the chair and CEO

roles that Dimon holds, a question he argues has no bearing on

shareholder value. Last year, 38% of shareholders supported a proposal

to split the positions. Investors in Goldman Sachs (GS.N) and

Bank of America (BAC.N) on

Wednesday rejected similar motions to clip the wings of the banks’

respective leaders – but in each case around one-third of investors

agreed with the proxy firms, who had supported the motions at both

banks.

Nor is the animosity unique to U.S.

companies. AstraZeneca’s chairman argued last week that proxy firms –

who opposed CEO Pascal Soriot’s $23 million maximum potential pay –

were doing “serious harm” to the competitiveness of British

businesses. Over one-third of the London-listed pharmaceutical

giant’s voting

shareholders rejected

its pay plan at the April 11 meeting.

Though the firms’ influence is hard to

gauge, it’s probably declining. Big fund managers like BlackRock (BLK.N) and

State Street (STT.N)

have their own stewardship teams and own a greater chunk of listed

companies than they used to. Studies that analyzed proxy firms’ impact

have reached different conclusions. One paper in 2010 estimated that

ISS’s advice shifts less

than 10% of

the vote. Another in 2022 suggested a much greater

influence over

institutional votes, if not retail ones. Some asset managers

“robo-vote” – meaning they automatically follow proxy advice. But

around 70% of ballot recommendations by Glass Lewis are customized to

client's preferences, for example. ISS is launching a bespoke menu for

conservative-leaning investors.

The process isn’t without its problems. For one, the guidelines the

firms draw up are based on principle - for example, the idea that an

independent chair is a better steward of a board than someone who is

also CEO – but not necessarily empirical fact. The proxy advisers also

adapt to local norms. Glass Lewis says large U.S. companies should aim

for a board that is at least 30% composed of gender-diverse

candidates. In Hong Kong, the lower limit is one diverse candidate.

It’s hard to find scientific reasons for either option.

Moreover, there’s not much accountability, because it’s hard to gauge

whether the recommendations were “right” or not. That makes proxy

advisers different from stock-picking analysts, say, whose

recommendations can have measurable monetary consequences for their

customers. Glass Lewis allows companies to file “unfiltered” rebuttals

which it then attaches to its reports, though very few do so.

There’s a further market failure: ISS and Glass Lewis have outsized

influence because they are effectively a duopoly. There are two likely

reasons for that. The barriers to entry for proxy advisers are high

given the sheer number of companies they cover. Furthermore, there’s

not much scope for deriving lavish profit, because it’s hard to make

investors value something that has no short-term impact on

performance. Fewer than one-third of retail shareholders bother to

vote at annual meetings, so it’s unlikely they would stomach higher

asset management fees for the vague promise of better long-term

governance.

Ultimately, proxy advisers do more good than harm. They at least

provoke debate on governance issues that otherwise might go without

much scrutiny. Even if they were to misfire, many of the votes on

which they opine, including “say on pay” at U.S. firms, are only

advisory. And as Disney, Goldman and Bank of America demonstrate,

investors still largely do what they’re told. The very fact that Dimon

can use JPMorgan’s annual report as an opportunity to bash proxy

advisers shows that the playing field is still firmly tilted in

executives’ favor.

Editing by Peter Thal Larsen and Aditya Sriwatsav

Opinions expressed are those of the author. They do not reflect the

views of Reuters News, which, under the Trust Principles, is committed

to integrity, independence, and freedom from bias.

© 2024 Reuters. |