Within the field of corporate governance, few issues

inspire as much fervor from critics as the use of

dual-class or multi-class share structures at certain

companies. In recent years, proxy advisory firms and

other self-proclaimed good governance advocates have

increasingly embraced the ‘one

share, one vote’ approach while castigating

companies with dual-class stock.

But our new, original analysis suggests that perhaps

dual-class shares are far from the malignant tumor its

critics would have you believe. One has to question

whether self-anointed governistas seeking to impose

single-share structures on all companies are

overreaching in their zeal for a universal,

one-size-fits-all solution when the reality is far

more nuanced.

Dual-class shares haven’t always been so unloved, and

a brief historical overview is warranted. Despite the

pendulum swinging far in favor of single class shares

and away from dual class shares in recent years within

the governista crowd, a review of academic literature

from corporate governance scholars and practitioners

over the last three decades reveals that this is a

divergence from the historical norm, which has long

held there is no one best way. Studies from sources as

varied as The

Harvard Business Review, Deloitte, The

Institute of Directors, Corporate

Board Member, MSCI, Dartmouth

University, The University

of Florida [here],

and

The University of

Singapore, all acknowledged both benefits

and disadvantages of dual and multi class shares.

As critics like to point out, the disadvantages

identified by these studies are obvious – dual class

shares create an inferior class of shareholders; can

increase the likelihood of related-party transactions;

diminishes independent/non-executive board leadership;

provides fewer checks and balances by more easily

allowing for entrenchment of existing management and

board; and could potentially deter institutional

ownership and impair access to debt and equity

markets.

But these studies also identified some

little-understood advantages of dual class shares: for

example, they facilitate easier execution of strategy;

insulate the firm and management from short-termism,

including activist shareholders; protects firms making

capital expenditures with long pay-off horizons, and

attracts the right kind of institutional investment

partners with long-term investment horizons.

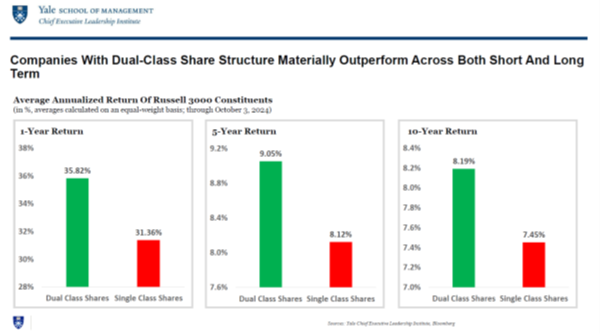

Our own analysis provides more evidence for the

historical consensus that there is no single best way

or one-size-fits-all solution. We evaluated the

stock performance of all companies in the Russell

3000, through October 3, 2024, separating out the

244 companies with dual class or multi

class share structures against the remaining companies

with single class shares.

The results were surprising. We found that companies

with dual and multi class shares, on average,

outperformed the companies with single class shares

across both the short and long-term. (all averages are

annualized and calculated on an equal-weight basis)

-

Over the past one year, companies with dual and

multi class shares have

returned 35.82% vs. 31.36% for

companies with single class shares.

-

Over the past five years, companies with dual and

multi class shares have

returned 9.05% vs 8.12% for companies

with single class shares.

-

Over the past ten years, companies with dual and

multi class shares have

returned 8.19% vs 7.45% for companies

with single class shares.

Our fresh quantitative analysis dovetails with prior

research; going back 20 years, many studies have demonstrated

how dual and multi class stocks outperform single

class shares over both short-term and long-term time

horizons.

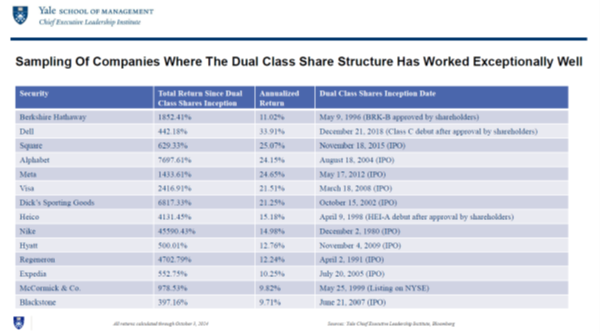

This outperformance is not just the product of

overweighting any one sector. Although it is easy to

associate dual class shares with new, buzzy technology

IPOs; in fact, our analysis found that

many of the most consistent, historic outperformers

within the Russell 3000 are dual and multi class stock

companies, such as Berkshire Hathaway, Visa, Nike,

Hyatt, Heico, Regeneron, McCormick & Co., and

Blackstone, representing virtually every sector of the

economy, and not just technology.

In evaluating dual-class share companies that have

consistently outperformed; while we acknowledge no two

situations are alike, there are some common patterns

which emerge. Some common scenarios when dual-class

shares seem to work especially well include:

-

When sui generis founder/owners are highly

personally engaged with record of success (such as

Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway and Michael

Dell at Dell)

-

Control shares pass to family/descendants of the

founder; but they have significant

industry/company expertise with demonstrated

successful track record of leadership before

assuming principal roles (such as the successful

transition from Ralph Roberts to his son Brian

Roberts at Comcast)

-

Control shares pass to family/descendants of the

founder without industry/company expertise; but

family entrusts competent professional management

team without unwanted interference/meddling (such

as at Hyatt and McCormick & Co.)

However, contrary to popular perception, dual class

shares are ultimately NOT just a bet on the sui

generis nature of an irreplaceable founder/controller

or the quality of a management team. Even beyond

leadership, we found there are common scenarios where

dual-class shares seem to work for structural business

reasons:

-

In certain highly cyclical industries where

inevitable, steep cyclical downturns periodically

create profiteering opportunities for activist

investors and hostile raiders if not for

dual-class shares, in cyclical sectors such as

financials and consumer discretionary. For

example, Hershey was nearly sold

for a quarter of its current market value during a

cyclical downturn, with the sale wisely

stopped only because of its dual class share

structure.

-

An ethos of long-term value creation is embedded

in the company culture vs. short-term profiteering

– allowing for stronger capital allocation

decisions, re-investment into the business, and/or

ESG prioritization. For example, unlike virtually

every peer, Berkshire Hathaway under Warren

Buffett has

never paid a dividend, with Berkshire’s

dual class share structure enabling Buffett to

substantively ignore occasional

sniping from speculators; over time,

the reinvestment of the company’s retained

earnings has proven to be 30 times more

financially accretive for shareholders than if

Berkshire had simply paid out regular dividends as

its peers did.

Of course, as critics note, and as is inevitable with

any governance structure, dual-class share structures

do not always succeed – though, curiously, none of the

most notorious corporate collapses and scandals took

place at companies with dual-class shares. Each of

Enron, Worldcom, Tyco, Arthur Andersen, Bear Stearns,

Lehman Brothers, Wirecard, Silicon Valley Bank, and

First Republic Bank had single-class share structures,

not dual-class shares; not to mention non-publicly

traded collapses at FTX and Theranos. Nevertheless, in

reviewing situations when dual-class shares turn ugly,

we found some common, repetitive pitfalls and red

flags:

-

When founder/owners have a reputation for

self-enrichment and/or using the company as a

personal piggy bank (for example, former CEO

Conrad Black of Hollinger International was indicted

for fraud after diverting company

assets and resources into his own hands)

-

When founder/owners age into infirmity but refuse

to relinquish control (for example, Sumner

Redstone refusing

to step down at Paramount/Viacom until

after multiple legal challenges and court

intervention)

-

When ill-prepared descendants of founders take

over companies without any experience/background

-

When descendants of founders needlessly meddle

with professional management teams

-

Destructive family infighting which leads to ugly

fissures and splits within control share blocs

and/or on the board

-

When controlling owners prioritize short-term

profit-taking and cash-outs in lieu of investing

for the long-term success of the enterprise

In light of these common pitfalls, it is worth noting

that a company’s optimal share class structure is far

from permanent, and can change with time. There are

many current situations, closely resembling the common

pitfall scenarios laid out above, where boards have

correctly concluded that dual class shares might have

made sense for those companies at some point in its

history, but not anymore. For example, Lionsgate

established a dual-class structure after its

acquisition of Starz in 2016, but now that Lionsgate

is spinning off Starz, Lionsgate is now

collapsing its erstwhile dual-class share

structure, heeding the wise encouragement

of constructive, engaged shareholders after

a prolonged period of poor market performance and

rumors of intra-board squabbling. Similarly, beer

maker Constellation Brands smartly

collapsed its dual-class share structure after

a major speculative

bet on marijuana gone wrong and other

questionable capital allocation and management

decisions fueled the stock’s underperformance against

peers.

In evaluating the outperformance of dual class shares

and in evaluating common scenarios where dual class

shares work especially well, balanced against common

pitfalls, the evidence is clear that for companies,

there is no single right answer between dual class,

multi class, or single class shares. It is all

situational, dependent on a company’s circumstances,

the demonstrated caliber of their leadership, and the

environment in which they operate. Just as dual class

shares are not the right structure for all companies;

dual class shares can make sense for certain

companies, in certain scenarios. These crucial nuances

are often lost in what has increasingly become the

single-minded zealotry of ‘one share, one vote’

advocates, seeking to impose single class structures

on all companies irrespective of circumstance.