|

Illustration: Virginia Gabrielli

|

Markets

| The Big Take

How Analyst Job Cuts on Wall Street Are

Reshaping Equity Research

Forces like regulation, passive investing and AI have all conspired to

squeeze equity research in ways few could have imagined. Countless

“sell-side” analysts have had to reinvent themselves as a result.

By Sujata

Rao, Denitsa

Tsekova, and Isolde

MacDonogh

January 8, 2025

at 5:00 PM EST

Jerry Diao had all the makings of a successful Wall Street

analyst. A degree in statistics from UC Berkeley. An MBA from NYU. And

a job in equity research at a big bank covering Silicon Valley tech

stocks.

But instead of a life of market-moving stock

calls, six-figure bonuses and glad-handing execs on another great

quarter of earnings, these days, Diao plies his trade on social

media, dishing out advice on the finance industry. On YouTube, Diao

goes by the nom de guerre “Richard Toad,” and until recently, he

masqueraded his irreverent

takes behind an avatar of Shrek.

It’s been humbling for Diao, who started out

in so-called sell-side research six years ago. He’s had to move back

home to Northern California, and despite a 40,000-strong following,

his “five-figure income” is just a third of what he used to earn. But

after trying, and failing, to get back into the industry after leaving

Wall Street in 2022, Diao has little choice. Making it as a “content

creator,” he says, is the No. 1 goal now.

|

Jerry

Diao previously used a "Shrek" avatar to hide his face in his

videos before going public.

Photographer: Mike Kai Chen/Bloomberg

|

“Maybe in hindsight, I will thank all the

companies that rejected me,” he said.

Diao, 37, is just one of scores of former

analysts who’ve had to reinvent themselves in recent years in the face

of a seismic upheaval reverberating through Wall Street.

The pandemic did, briefly, fuel a burst of

hiring in equity research but when it faded, it left the same potent

forces in place that have been gutting the industry for years. Regulations on

how banks charge for research, a shrinking market

for publicly listed companies, and the popularity of index-tracking

funds have conspired to squeeze equity research in ways few could have

imagined even a decade ago. Leaps in artificial intelligence only

threaten to accelerate that

trend, with firms like JPMorgan already experimenting with AI-powered

analyst chatbots,

sowing deeper doubts about the value of fundamental analysis and

whether investors will keep paying for it.

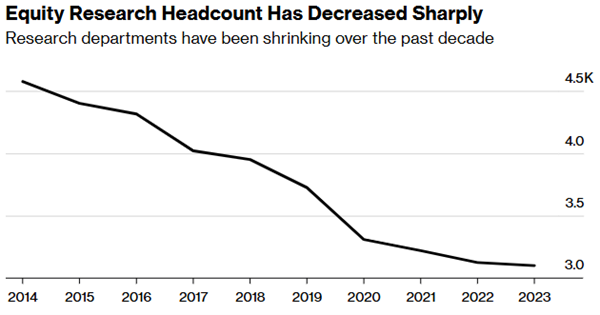

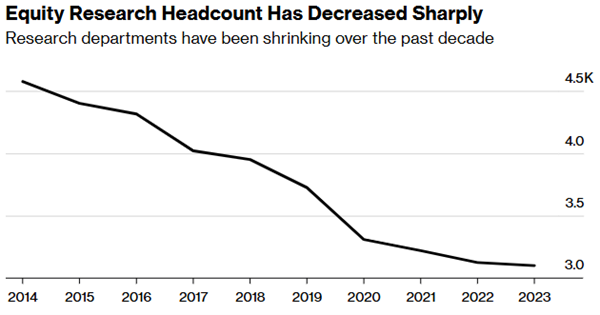

Compared with their post-financial crisis

peak, it’s estimated that the biggest banks globally have slashed the

ranks of equity analysts by over 30% to lows not seen in at least a

decade. Those who remain often cover twice, or even three times, as

many companies.

The fallout is already

reshaping Wall Street.

And the pay, while still far higher than most jobs in industries

outside finance, has stagnated. For example, starting salaries for

entry-level equity analysts currently range from $110,000-$170,000 a

year, barely above their levels before the financial crisis, according

to Vali

Analytics.

They have been climbing of late — up by some

$20,000 on average from a low in 2020. But after taking inflation into

account, total compensation remains about 30% lower than it was

pre-crisis, the data show.

The fallout is already reshaping Wall Street.

It’s also having knock-on effects on the structure of the stock market

itself, in how individual companies, both big and small, are valued.

(More on that later.)

No one expects compensation to return to the

heyday of the late ’90s and early 2000s, of course, when star analysts

like Mary Meeker and Jack Grubman were fêted like celebrities and

reportedly made upwards of $15 million or more, and stock

recommendations, more often than not, were geared toward winning

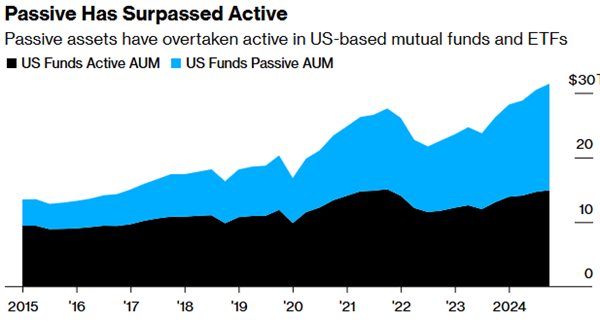

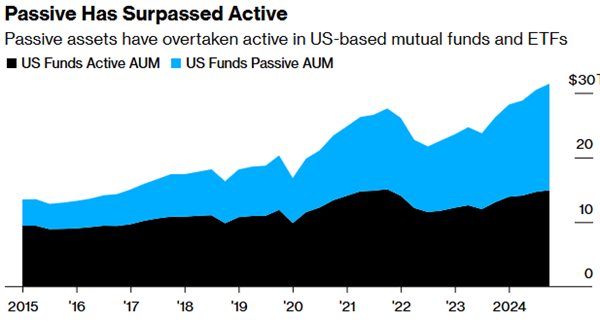

underwriting business for their banking arms. And it’s not too hard to

understand why equity analysts might be in the crosshairs as

automation proliferates, investors embrace cheap, passive-investing

strategies like ETFs and the broader market keeps hitting record after

record.

Nevertheless, the numbers underscore an

industry in steep decline.

At the world’s 15 biggest banks, the number

of equity analysts has fallen to about 3,000 from almost 4,600 a

decade ago, according to Vali Analytics. The biggest cuts have

occurred in Europe and Asia, excluding Japan. Data from Coalition

Research shows a similar decline. Apart from an outlier or two,

the reductions have been widespread and few equity research

departments have been spared. Industry insiders say Citigroup and

Deutsche Bank were among the more notable banks in paring headcount.

Both declined to comment. (Bloomberg LP, the parent company of

Bloomberg News, produces equity research that competes with analysis

from Wall Street firms.)

|

Source: Vali Analytics. Data cover

cash equity research headcount at the world’s 15 biggest banks

|

Meanwhile, despite a small uptick in the

first half of last year, spending on research globally has sunk 50%

since 2018, data from Substantive Research show. That year, MiFID

II was enacted, forcing asset managers in the UK and European

Union to pay for research, rather than offering it for free as part of

a suite of services. US brokers supplying research to Europe-based

managers also became subject to the rule two years ago.

The result? Equity research has become “an

orphaned child that’s always looking for a home,” according to Robert

Buckland, who was Citigroup’s head of equity strategy until 2023.

Some former analysts have managed to find

work at hedge funds, while others have jumped ship to work in investor

relations at firms they once covered. Buckland himself is now at a

startup called EngineAI, which applies AI programs to various fields,

including equity research.

For those who have stuck around, job security

is tenuous.

Take, for instance, George O’Connor. The

technology analyst has bounced around London from one firm to the next

in recent years, and has now worked for a half-dozen shops since

becoming an equity analyst in the late 1990s. Currently at Progressive

Equity Research, O’Connor says the “unbundling” of research from

trading, ostensibly meant to level the playing field, gave big banks

an upper hand because they could charge less for more wide-ranging

coverage.

“There was also a flight to cheap driven by

much larger global providers, which sort of knocked smaller companies

out of the water,” he said. “It’s just economics 101.”

You don’t get the “same level

of information you had when a

company had 20 people covering

it.”

Individual analysts are saddled with more

companies to cover, leaving less time for in-depth analysis. According

to Zaki

Ahmed, a veteran headhunter who runs recruiting firm Financial

Search, banks often want analysts to cover as many as 20 stocks as

they shrink their research teams.

The buyside is feeling the pinch, too. Matt

Stucky, a money manager at Northwestern Mutual Wealth Management, says

there either simply aren’t enough analysts covering the companies he’s

interested in or they’re spread too thin. As a result, he’s had to do

more of the legwork himself to get the answers he wants.

You don’t get the “same level of information

you had when a company had 20 people covering it,” Stucky said.

Currently, companies in the Russell 2000

Index with fewer than 10 analyst recommendations have ballooned to

some 1,500 from 880 a decade ago, an increase of 70%, data compiled by

Bloomberg show. Conversely, coverage has become concentrated in the

biggest names. Today, about 97% of the S&P 500 have 10 or more

ratings, up from about two-thirds in 2014.

A growing body of evidence suggests stocks

that fall off the sell-side radar often struggle to attract investors,

distorting valuations and making markets less efficient.

One academic paper,

which looked at data over a 40-year period, showed how investors

consistently over- or undervalued companies covered by fewer analysts.

Another study found firms

that had a decrease in coverage showed a significant decline in

investor recognition, increasing their cost of capital. A third showed

that low-coverage stocks traded less and had wider bid-ask spreads,

while “orphaned” companies were far more likely to be delisted.

They’re also more likely to underperform.

Small-cap companies with no coverage, for example, have lagged behind

those covered by more than 10 analysts by nearly 3 percentage points a

year since 2001, according to Steven DeSanctis, a small- and mid-cap

strategist at Jefferies.

|

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence

|

“For small companies that are already covered

by fewer analysts to start with, each one less will hurt them more,”

said Kevin

Li, a professor at Santa Clara University and co-author of one of

the papers. “The downtrend is probably not preventable, given the move

away from active investment. Now, with AI, we could see that (human)

role reduce further.”

Part of the irony is that the lack of

in-depth analysis which asset managers bemoan is a direct consequence

of their unwillingness to pay for it. And as they “continue to spend

less and less” for bank research, Integrity Research’s Mike

Mayhew says they’ll likely look for more cost-effective ways to

fill the gaps.

That includes relying on in-house analysts or

non-bank sources like those on blogging platform Substack, often

written by the very analysts caught up in budget cuts and staffing

culls. Northwestern Mutual’s Stucky subscribes to a few himself and

values their “unfiltered” takes. (He declined to identify them.)

Indeed, online finance blogs have exploded in

recent years, with Substack estimating it now hosts tens of thousands

of them.

One is written by Alex

Morris. He runs TSOH Investment Research (it stands for The

Science Of Hitting — he’s a big baseball fan), which has

racked up nearly 700 paid subscribers since 2021. At $499 annually,

that equates to roughly $260,000 a year after fees, etc. — more than

double what he earned at the Fiduciary Group, a small investment

adviser in Savannah, Georgia.

Morris discloses his recommendations at 5

p.m. Eastern time and then invests in them the next day. Last year,

his 10-stock portfolio, which included Netflix and Meta, returned 21%,

versus the S&P 500 Index’s 23% gain. It’s the third time in the past

four years that he’s fallen short of his benchmark, yet he’s continued

to attract followers despite his mixed record.

Asked why they should stick with him rather

than buying an ETF, Morris says history suggests the S&P 500’s outsize

gains won’t likely last. Part of his draw, he says, is that he talks

about his winners and losers and puts all his investable assets behind

his calls.

“The industry has had issues in the past in

terms of what the person writing the research actually thinks, versus

what they would do if they were managing their own money,” he said.

Another is by Barry

Knapp, a longtime strategist who built a following over four

decades on Wall Street with Lehman Brothers, BlackRock, and most

recently, Guggenheim. He currently has “hundreds” of paying Substack subscribers,

each of whom forks over $999 a year for his macro research.

His home office faces the slopes of Vail,

Colorado, a nice change from his commutes into Manhattan. But Knapp

says that even with his résumé and built-in following, the market for

sell-side research isn’t what is used to be.

“For someone like me to go back and work on

the Street for a number that is not even close to what I was making in

2000?” Knapp mused. “What would be the point?”

|

Jerry Diao

Photographer: Mike Kai Chen/Bloomberg

|

Reliable figures on how lucrative financial

blogging is as a full-time profession are scant, as is data on how

many analysts have parlayed their Wall Street bona fides into genuine

success on social media. While some, like Morris and Knapp, have

managed to make it work, the signs suggest that most end up toiling

away in relative obscurity.

Back in the San Francisco Bay Area, Diao

continues to create content on YouTube, Substack and Instagram, hoping

one day to break through.

He touts the benefits of his newfound

vocation. No need to dress up or commute to the office, no more

80-hour weeks. He can produce all his blogs and podcasts in his

bedroom with a laptop and a microphone.

All he needs now is a little bit of luck —

and a few more paying subscribers.

“These kinds of things, once they hit

critical mass, can suddenly become big enough to pay rent and put

meals on the table,” Diao said. “And at this point, that’s all I’m

hoping for, because the freedom that comes with it, you can’t put a

price on that.”

| ©2025 Bloomberg

L.P. All Rights Reserved. |

|