|

THE WALL STREET

JOURNAL. |

MARKETS

|

Markets

Buyout Shops Look to Rivals for

Deals

|

|

By

Ryan Dezember

July 30, 2014 5:20

p.m. ET

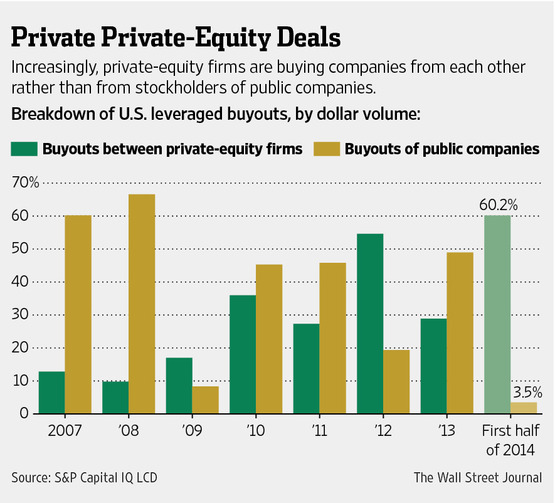

Private-equity firms have all but stopped buying public companies,

retreating from a cornerstone of their business as rising stock prices

push acquisition targets out of reach.

Public companies taken private accounted for 3.5% of the $89 billion

of U.S. leveraged buyouts in the first half of this year, the lowest

share on record, according to data tracker S&P Capital IQ LCD. In the

first half of 2008, at the apex of a buyout boom, these types of deals

represented about 68% of all buyouts by dollar volume.

Instead, private-equity firms are buying companies from one another, a

shift driven in part by the relative simplicity of completing an

acquisition of a private company compared with a publicly traded one.

Transactions between private-equity firms have made up 60% of U.S.

leveraged buyout volume through June, according to S&P. That is a

higher percentage than the ratio for any full year tracked by the

firm, whose data date to 2002.

Overall dollar volume of U.S. leveraged buyouts through June was up

30% over the same period a year ago.

Carlyle Group

LP this week said it would buy Acosta Inc., a marketing firm that

helps consumer-goods companies launch products and track sales, from

Thomas H. Lee Partners LP. Carlyle is paying roughly $4.8 billion,

according to people familiar with the matter, making the deal one of

the year's largest buyouts.

The Jacksonville, Fla., company has had four private-equity owners

since 2004, including Carlyle, an increasingly common occurrence for

businesses that generate enough cash to keep up with payments on the

debt that private-equity firms use to buy and extract dividends from

companies.

The trend marks a big change from earlier eras of private equity, when

buyout firms plucked multibillion-dollar companies off the stock

market with regularity. The bidding war leading up to KKR & Co.'s $25

billion buyout of RJR Nabisco Holdings Inc., in 1988, was detailed in

a best-selling book, "Barbarians at the Gate," and a movie.

That deal opened the door to a burst of public-company takeovers in

subsequent years and in the run-up to 2007's financial crisis.

The handful of public companies to go private this year are tiny in

comparison. The largest deal has been

Apollo Global Management LLS’s

$1.3 billion takeover of Chuck E. Cheese parent CEC Entertainment Inc.

The other four, a maker of robotic cutting tools and a real-estate

developer among them, cost private-equity buyers less than $400

million apiece.

"There have been some lessons learned," said David Mussafer, managing

partner at Advent International, which is investing a $10.8 billion

fund. "The badge of honor comes from the returns you generate for your

fund, not the size of the deal."

Private-equity firms combine investors' cash and borrowed money to buy

companies with the aim of selling them profitably a few years later.

Public companies have historically been a top target, along with

family-owned businesses and divisions carved out of corporations.

Purchases of companies owned by buyout industry rivals aren't new, but

they have become more frequent.

Higher stock prices are one reason, as they drive up public-company

valuations. After a number of large deals backfired on private-equity

firms amid the financial crisis, the companies since then have

generally shied away from big buyouts.

The S&P 500 index soared 30% in 2013 and is up 6.6% this year.

Plus, with the rise of acquisition activity this year, corporate

buyers who for long sat on the sidelines are now competing for deals.

Some say the private deals are proving good for business. On a call

Wednesday discussing Carlyle's second-quarter results, co-Chief

Executive David Rubenstein said returns on these deals "have been

pretty robust for investors in recent years, and I think, therefore,

you're likely to see more."

Private-equity executives also say deals with peers are simply easier.

The stock market's run has prompted private-equity firms to seek ways

to cash out of older investments in droves, making these firms

motivated sellers, unlike many public companies that resist takeovers.

And public-company buyouts are more complex. They can require

postagreement auctions, called "go-shop" periods, in which boards seek

higher offers. Shareholders must approve deals. Lawsuits from

shareholders challenge nearly every deal. Activist investors can enter

the fray and agitate for higher prices.

"If you have a choice between a public company and a private company

in the same industry, certainty of closing is much greater in a

private deal," said Mel Cherney, co-chairman of the corporate

department at law firm Kaye Scholer LLP.

Meanwhile, private-equity firms need to find companies to buy, if not

public, then private. They have about $326 billion to put to work in

buyouts, according to data provider Preqin.

Criticism of deals between firms has focused on what value one manager

can bring after another has owned the company.

Mr. Rubenstein of Carlyle on Wednesday said that the deals "have had

their ups and downs in terms of the way that people look at them" and

the key is to "have a good management approach and a plan when you're

buying."

A 2012 study by three European researchers compared the results of

more than 5,300 leveraged buyouts from 1986 to 2007 and found that

there often wasn't a big difference in performance between the 435

deals made between investment firms and buyouts of companies with

other types of owners.

The researchers said the downside of these deals is limited, and so,

too, is the upside.

Write to

Ryan Dezember at

ryan.dezember@wsj.com

|