|

Law360, New York (August 07, 2014,

10:36 AM ET)

--

Delaware appraisal actions are on

the rise, primarily due to the new

and expanding phenomenon of

“appraisal arbitrage” — in which

shareholder activists and hedge

funds acquire target shares after a

merger is announced and focus on

asserting appraisal claims as a kind

of investment in and of themselves.

From 2004 through 2010, the number

of appraisal petitions filed in

Delaware rose and fell roughly in

parallel with the overall level of

merger activity, with appraisal

rights being asserted in about 5

percent of the transactions for

which they were available. In 2011,

however, the rate of petitions more

than doubled (to 10 percent) and it

has continued to increase. In 2013,

28 appraisal petitions were filed in

Delaware, representing about 17

percent of appraisal-eligible

transactions.

In 2014, so far, more than 20

appraisal claims already have been

filed in Delaware. The amounts at

stake in appraisal actions have

increased as well, with the value of

dissenting shares in 2013 ($1.5

billion) being 10 times the value of

dissenting shares in 2004, and more

than five times the value of

dissenting shares over their highest

point in the last five years. Of the

eight appraisal proceedings between

2004 and 2013 that involved more

than $100 million worth of

dissenting shares, four of them

occurred in 2013. (This data is

derived from a report by law

professors Charles R. Korsmo and

Minor Myers.)

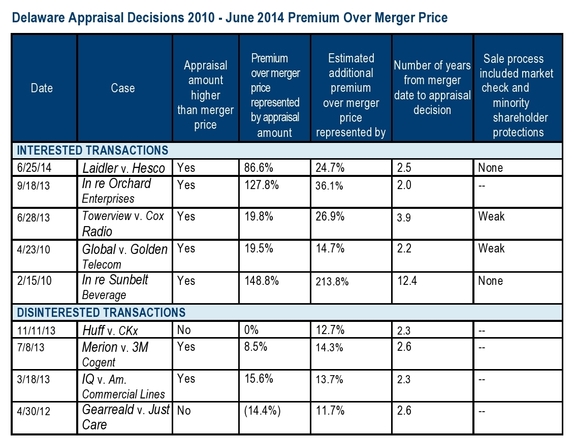

In our review of Delaware post-trial

appraisal decisions from 2010 to

June 2014 (see chart below), we

found that the court’s determination

of fair value was higher than the

merger price in seven of the nine

cases. The highest premium

represented by the appraisal award

over the merger price was 148.8

percent — without even considering

the award of statutory interest

(which, in that case, represented an

additional premium of 213.8 percent

above the merger price). There was

only one case in which the appraisal

award was lower than the merger

price (representing a 14.4 percent

discount to the merger price); and

only one case in which the appraisal

award was the same as the merger

price.

In the five cases that the court

viewed as “interested transactions”

(i.e., controlling stockholder or

parent-subsidiary mergers), the

appraisal award was significantly

above the merger price — with

premiums of 19.5 percent, 19.8

percent, 86.6 percent, 127.8 percent

and 148.8 percent, respectively.

Taking into account the statutory

interest awards in these cases,

there was an additional premium of

approximately 14.7 percent, 26.9

percent, 24.7 percent, 36.1 percent

and 213.8 percent, respectively.

While the extent of the market

checks and protections afforded to

the disinterested shareholders in

these transactions varied, the range

was from none to relatively weak.

Notably, the two highest fair-value

premiums (148.8 percent and 86.6

percent — we have excluded the 127.8

percent premium because it was based

almost entirely on an issue relating

to interpretation of preferred stock

terms and so is not relevant in this

context) were awarded in the only

two cases in which there were no

market checks or minority

protections whatsoever.

For example, the backdrop to the

case with the highest premium was an

arbitration panel determination that

the only reason for the merger was

to eliminate the petitioner as the

sole remaining minority shareholder

— “without notice and without legal

justification ... [and through the

controlling stockholder’s use of]

strong-arm tactics.”

By contrast, in the four

transactions viewed by the court as

“disinterested” (i.e., third party

arm’s-length transactions), the fair

value determination was higher than

the merger price in only two of

them. Further, these premiums, 8.5

percent and 15.6 percent, were

considerably lower than the premiums

in the interested transactions.

|

Critically, notwithstanding the

notable increase in appraisal

activity, it is still only a fairly

low percentage of all appraisal

eligible transactions (17 percent in

2013) that currently attract

appraisal petitions. (By contrast,

almost all strategic transactions

now attract litigation with breach

of fiduciary duty claims.) Moreover,

while the only consideration in an

appraisal proceeding is the

determination of fair value (and

wrongdoing by the target board or

flaws in the sale process are

legally irrelevant for these

purposes), the transactions that

attract appraisal petitions

generally involve some basis for a

belief that the deal price

significantly undervalues the

company — that is, controlling

stockholder transactions, management

buyouts, or other transactions for

which there did not appear to be a

meaningful market check or

significant minority shareholder

protections as part of the sale

process.

This

Quarter’s Delaware Appraisal Cases

Court Declines to Use

Merger Price as a Basis for

Determining Fair Value:

Laidler v. Hesco (May

12; June 25)

Vice Chancellor Sam Glasscock

declined to use the merger price as

a basis for determining “fair value”

in an appraisal proceeding.

Glasscock had recently decided, in

Huff v. CKx (November 2013), in a

departure from recent Delaware court

practice, to use the merger price as

the basis for determining appraised

fair value. In Hesco, Glassock

distinguished CKx, emphasizing that

the CKx transaction had been fully

arm’s length, there was a

competitive auction, and the court

had determined that no other

financial analysis to determine fair

value was available because of the

high degree of unreliability of

management’s projections.

The merger in Hesco, however — where

the 90 percent parent “itself

decided the price” to pay to the

sole remaining minority shareholder

of its subsidiary in a short-form

merger — was “nothing like” the

arm’s-length competitive auction

process pursuant to which the merger

price was determined (and then

approved by a minority shareholder

vote) in CKx.

With the facts of the CKx

transaction at one extreme with

respect to process protections and

those of Hesco at the other extreme,

it remains unclear whether, and to

what extent, the court will be

inclined to use a merger price as

the basis for appraised fair value

in the context of an arm’s-length

transaction where other financial

analyses are available (or, where

they are not available and there has

been a market check but the market

check was less than perfect).

Also of interest, in Hesco, the

court adopted, for the first time, a

direct capitalization of cash flow (DCCF)

methodology for determining fair

value (rather than the discounted

cash flow (DCF) method usually used

by the court). Both parties’ experts

had agreed that DCCF was the most

appropriate methodology in this case

because of management never having

made cash flow projections in the

ordinary course of its business,

together with the uncertain nature

of the company’s future revenue (due

to its standing to lose the patent

on its primary product and the

unusual nature of its business in

which its primary product is

purchased only in anticipation of or

after major natural disasters).

DCCF differs from DCF in that DCF

projects cash flows over a horizon

period and estimates a terminal

value at which cash flows can be

valued in perpetuity, and then

discounts to present value those

cash flows over multiple periods,

while DCCF estimates a normalized

level of cash flows in perpetuity

and divides those cash flows by a

capitalization rate to estimate the

present value of the business. In

Hesco, the merger price offered to

the dissenting shareholder had been

$207 per share; petitioner’s and

respondent’s experts, both using the

DCCF methodology, had determined

fair values of $515 and $250,

respectively; and the court

determined fair value to be $387.

Voting Issues Cloud

Appraisal Rights:

Merion Capital/Ancestry.com

and Merion Capital/Dole

Food (Both Proceedings are

Pending)

Merion Capital, a hedge fund that

focuses on appraisal arbitrage, is

seeking appraisal of the

Ancestry.com shares it purchased

after Ancestry.com was acquired by

an investor group led by private

equity firm Permira, and the Dole

Food shares it acquired just before

the Dole management buyout. An issue

in both proceedings is that it is

only shares that do not vote for a

merger that are entitled to

appraisal.

It can be difficult to establish how

shares have been voted in two

situations: first, if the shares are

held in street name, in which case

they are voted in the aggregate by

the depositary (albeit in accordance

with instructions from the

beneficial owners), and second, if

the shares are acquired after the

record date for the merger and so

were voted by the previous owner.

The Delaware Supreme Court, in its

2007 Transkaryotic decision,

established that, as shares held in

street name are voted in the

aggregate without attribution to the

beneficial owners, street shares

would be entitled to appraisal

rights so long as the total number

of street shares seeking appraisal

did not exceed the total number of

shares that the depositary voted

against the merger.

In Ancestry, Merion acquired the

shares after the record date for the

merger and did not know how they had

been voted. As the shares are held

in street name, Merion has assumed

that Transkaryotic would apply.

Ancestry has argued, however, in a

brief filed in May, that, since the

law changed after Transkaryotic to

permit beneficial holders (and not

just record holders) to assert

appraisal rights, the beneficial

owner (and not only the record

holder) now has the statutory

obligation to show how its shares

were voted.

The issue that has arisen in the

Dole proceeding is that more shares

are seeking appraisal than have

voted against the merger.

It is not known how the court will

view these issues. Their resolution

may significantly affect

shareholders’ ability to seek

appraisal — especially activist

shareholders and hedge funds that

engage in appraisal arbitrage (and

so often buy shares after the record

date).

—By Abigail Pickering Bomba, Steven

Epstein, Arthur Fleischer Jr., Peter

S. Golden, David Hennes, Renard

Miller, Philip Richter, Robert C.

Schwenkel, David N. Shine, Peter

Simmons, John E. Sorkin and Gail

Weinstein,

Fried Frank Harris Shriver &

Jacobson LLP

Abigail Pickering Bomba,

Steven Epstein,

Peter Golden,

David Hennes,

Philip Richter,

Robert Schwenkel,

David Shine,

Peter Simmons and

John Sorkin are partners in

Fried Frank's New York office.

Arthur Fleischer and

Gail Weinstein are senior

counsel in New York.

Renard Miller is an associate in

the firm's Washington, D.C., office.

The opinions expressed are those of

the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the firm, its

clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or

any of its or their respective

affiliates. This article is for

general information purposes and is

not intended to be and should not be

taken as legal advice.