Appraisal Arbitrage—Is

There a Delaware Advantage?

Posted by Gaurav Jetley and Xinyu Ji,

Analysis Group, Inc., on Monday, July 27, 2015

|

Editor’s Note:

Gaurav Jetley is a Managing Principal and

Xinyu Ji is a Vice President at Analysis Group, Inc. This post

is based on a recent article authored by Mr. Jetley and Mr. Ji.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

This post is part of the

Delaware law series, which is cosponsored by the Forum and

Corporation Service Company; links to other posts in the series

are available

here. |

Market observers have

devoted a fair amount of attention to possible reasons underlying the

recent increase in appraisal rights actions filed in the Delaware

Chancery Court. A number of commentators have connected such an

increase to recent rulings reaffirming appraisal rights of shares

bought by appraisal arbitrageurs after the record date of the relevant

transactions. Other reasons posited for the current increase in

appraisal activity include the relatively high interest rate on the

appraisal award and a belief that the Delaware Chancery Court may feel

more comfortable finding fair values in excess of, rather than below,

the transaction price.

In our paper

Appraisal Arbitrage—Is There a Delaware

Advantage?, we examine the extent to which economic

incentives may have improved for appraisal arbitrageurs in recent

years, which may help explain the increase in appraisal activity. We

investigate three specific issues.

First, we examine the

economic implications of permitting appraisal rights to shares that

were purchased after the record date. The ability to delay the

investment allows appraisal arbitrageurs to get a better sense of the

value of the target, while at the same time helping reduce their

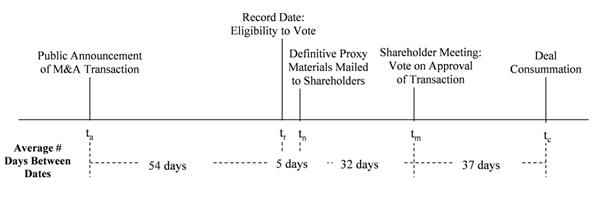

exposure to the risk of deal failure. Figure 1 shows the typical time

line of a friendly all-cash deal. As shown in the figure, in general,

there are over two months between the record date and the deal

closing. Postponing the share purchase to after the record date

enables arbitrageurs to take advantage of information that may not

have been available as of the record date. Casual observation of the

financial markets suggests that a lot can change over a two-month

period. Postponing the investment decision to as near the deal closing

as possible also helps arbitrageurs minimize or eliminate deal risk (i.e.,

the risk that the deal will not close). Thus, allowing appraisal

arbitrageurs to delay their investment in target company stocks by

about two months is akin to giving them a valuable option, which helps

arbitrageurs both increase return and lower risk.

Figure 1: Timeline

of a Typical Deal Process

Second, recent rulings

in appraisal matters have signaled a preference by the Delaware

Chancery Court for the discounted cash flow (“DCF”) valuation method

in determining the fair value of the target stock. We examine the

extent to which the Chancery Court’s preferences, with respect to

certain inputs to the DCF method, may be affecting economic incentives

for appraisal arbitrageurs. We find that recent rulings in appraisal

proceedings suggest that the Court prefers to use the supply-side

equity risk premium (“ERP”) in computing the target firm’s cost of

equity. While using the supply-side ERP is consistent with the view

generally accepted by academic researchers that, going forward, the

ERP is likely to be lower than was observed in the past, it may be

inconsistent with the common practice of investment bankers advising

M&A deals. Figure 2 compares ERPs reported in a sample of target

company proxy filings to contemporaneous supply-side ERP measures. It

shows that nearly two-thirds of the time, target financial advisors

adopted a higher ERP. This finding implies that appraisal arbitrageurs

may be able to take advantage of the wedge between the valuation

inputs commonly used by investment bankers providing fairness opinions

to parties in M&A transactions and those preferred by the Court.

Figure 2: ERP

Inputs Used by Target Financial Advisors vs. Supply-Side ERPs

in Selected Transactions

In addition,

Delaware’s appraisal statute requires the court to determine a point

estimate, rather than a range, of the fair value of the target

company. Thus, transactions consummated at a price that is on the

lower end of the DCF value range established by the target’s financial

advisors might be more attractive to appraisal arbitrageurs, because

arbitrageurs could start by showing that the fair value of the target

is at least equal to the mid-point of the target financial advisor’s

DCF value range. Figure 3 compares the transaction price in a sample

of M&A deals during the 2010-2014 period to the DCF valuation range

established by the target’s financial advisors. It shows that over one

third of the deals were consummated at a price below the midpoint of

the DCF range. This fact alone does not mean that the Delaware

appraisal statute gives appraisal arbitrageurs any particular

advantage. However, a combination of various factors, including

Delaware’s preference for the supply-side equity risk premium, the

statutory requirement for determining a point estimate of value, and

the Court’s historical reluctance to give the actual transaction price

much weight under an appraisal proceeding, does present a favorable

environment for appraisal arbitrageurs.

Figure 3: Deal

Prices Relative to DCF Price Ranges Established by Target Financial

Advisors

Finally, we benchmark

the Delaware statutory rate on the appraisal award to yields on the

U.S. Treasury Bonds as well as corporate bonds with maturity and

credit risk that correspond to risk of appraisal (three-year with

credit ratings of “BB” or higher). Figure 4 shows that the statutory

rate, set at the Federal Reserve Discount Rate plus 5%, is higher than

the benchmark yields. Thus, the Delaware statutory rate compensates

appraisal petitioners for significantly more than the time value in

question, and in instances where the credit rating of the surviving

entity after an M&A deal is at least “BB,” the statutory rate more

than compensates petitioners for a bond-like claim. While it is

debatable whether the extent to which an arbitrageur’s decision to

seek appraisal is driven by the statutory rate, our findings are

consistent with the notion that the relatively high current statutory

rate does improve the economics for arbitrageurs.

Figure 4:

Benchmarking the Delaware Statutory Rate Against Selected Benchmark

Interest Rates, 2010 to 2014

A few policy

implications flow from our results: First, from an economic

perspective, it seems reasonable to limit a dissenting shareholder’s

appraisal rights to only the shares held as of the record date.

Setting the cut-off at the record date, instead of at an earlier time,

such as the deal announcement date, allows an appraisal arbitrageur

time to evaluate whether to purchase a target company’s stock for

purposes of bringing an appraisal claim later. At the same time,

denying appraisal rights to shares acquired after the record date

helps reduce the value transfer (i.e., the value of the delay

option) from the acquirer/target to appraisal arbitrageurs.

Second, with respect

to the potential wedge between the Court’s preference and investment

bankers’ common practices for certain valuation inputs, we do not

suggest that the Court should simply adopt investment bankers’

valuation assumptions, as doing so would defeat the purpose of an

appraisal action. However, our findings do indicate that the Court may

want to be mindful of certain systematic differences in valuation

inputs which could create profiteering opportunities for those seeking

appraisal. Conversely, investment bankers and deal lawyers should also

be sensitive to these systematic differences, and should at least be

aware of the potential implication of continuing to adopt certain

valuation assumptions. With respect to the Court’s practice of giving

little weight to the merger price in determining fair value, we

suggest that, in the absence of a finding of a flawed sales process,

it might be useful for the Court to keep the actual transaction price

in mind when appraising the fair value of a publicly traded target

company. Furthermore, even in instances where the sales process is

less than ideal, it may still be useful to subject the DCF value of a

publicly traded target to some form of a market check.

Finally, our

benchmarking analysis of the Delaware statutory interest rate

indicates that it may be useful to contemplate a change in either the

interest rate itself or the amount on which the interest rate is paid

(or both). We recognize that it may not be possible to set an interest

rate based on the characteristics of a target or an acquirer without

increasing the scope of issues that are likely to be litigated in an

appraisal proceeding. Given this consideration, it may be more

practical to adopt a change that limits the amount on which the

interest rate is paid. On that regard, the recent proposal by the

Council of the Delaware Bar Association’s Corporation Law Section to

limit the amount of interest paid by appraisal respondents—by allowing

them to pay appraisal claimants a sum of money at the beginning of the

appraisal action—seems like a practical way to address concerns

regarding the statutory rate. However, at the same time, such a

practice might further encourage appraisal arbitrage, because paying

appraisal claimants a portion of the target’s fair value up front

effectively supplies capital to claimants to pre-fund their appraisal

pursuits.

The full paper is

available for download

here.

|

Harvard Law School Forum

on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation

All copyright and trademarks in content on this site are owned by

their respective owners. Other content © 2015 The President and

Fellows of Harvard College. |

|