|

The column below was distributed to Forum participants with an invitation to comment on the issue of anonymity as it relates to both the standards defined for investor communications in the recent "E-Meetings" program and the Shareholder Forum's privacy policies stated in its own Conditions of Participation. |

Financial Times, September 1, 2011 column

|

August 31, 2011 9:16 pm It is right to curtail web anonymity By John Gapper

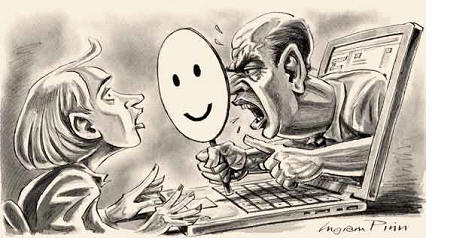

One of the founding principles of the web – not only the technology but the culture that has grown up with it – is that, as the New Yorker cartoon once put it: “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” The policy that people are free to interact online anonymously – or at least using pseudonyms – is now under attack from social networking companies. Both Faceboook and Google, which in June launched a competing service called Google Plus, have cracked down on people trying to use pseudonyms rather than full identities. “The internet would be better if we had an accurate notion that you were a real person as opposed to a dog, or a fake person, or a spammer,” Eric Schmidt, Google’s chairman, said at the Edinburgh International Television Festival last week. He was echoing Randi Zuckerberg, Facebook’s former marketing director, who declared earlier this year that: “anonymity on the internet has to go away.” These arguments are half right. Anonymity should not be banned in every corner of the internet any more than it is in the physical world in democracies – it would breach civil liberties. But there are good reasons to discourage it. Most users would gain if anonymity were the exception rather than the rule. Mr Schmidt and Ms Zuckerberg (whose brother Mark, Facebook’s founder, has attacked the use of multiple identities as displaying “a lack of ethics”) have been criticised for their remarks. “The desire to clean up the web, civilise it, and sterilise it pisses me off. I hate it,” Fred Wilson,a venture capitalist, wrote earlier this month. The right to anonymity when voicing opinions helps to prevent victimisation. Democracies permit citizens to vote anonymously and the US Supreme Court declared in a 1995 case that: “Anonymous pamphleteering is not a pernicious, fraudulent practice, but an honourable tradition of advocacy and dissent. Anonymity is a shield from the tyranny of the majority.” The web equivalent of anonymous pamphlets – taking to Twitter or to microblogs in China and in Arab countries to demand accountability or freedom from undemocratic governments – is a vital use of the internet. If everyone not only had to be identified but could be traced by security services, freedom of expression would suffer. That is why it would be wrong, even if it were practical, to rewrite the underlying technology of the internet to introduce what Mr Schmidt calls “strong identity” and make every user easily identifiable and traceable. At a stroke, that would curtail many valid forms of online interaction. Governments and law enforcement agencies have other mechanisms to track down criminals, whether they are inciting riots on social networks, sending pornography and spam, hacking, or stealing money. There is no need to force everyone online to carry an identity card. Yet the fact remains that, as Ms Zuckerberg put it: “People behave a lot better when they have their real names down … I think people hide behind anonymity and they feel like they can say whatever they want behind closed doors.” The prevalence of anonymity in online debates has helped to spawn a culture of aggression. Not only are many sites plagued by “trolls” and “flame wars” between rivals but anonymity can be abused to bully others and be unpleasant. Some of this behaviour would still occur if people had to use their own names. The advantage of web self-expression – the broadening of civic engagement – comes with the drawback of incivility: it is hard to achieve one without the other. But anonymity increases the incentives to behave badly. The effect can be to diminish participation rather than increase it – amid so much noise it is harder to know what is valuable. Many people are put off by the atmosphere and moderate voices are thus crowded out by extreme ones. This is not merely an aesthetic judgement about how robust and plainspoken online debate ought to be. Anonymity, whether in mainstream media outlets or on the web, also makes it harder to know about other people’s conflicts of interest and how seriously their views should be taken. These problems are partially mitigated by pseudonymity instead of complete anonymity – the use of avatars and pseudonyms so that sites can identify and weed out persistent mischief-makers and users gain a sense of others’ personalities. But it does not solve them. So it is welcome that companies such as Facebook and Google are taking a stance on anonymity. They have self-interested reasons to do so, since the more data their users give them, the more valuable their networks become to advertisers, but it is a good idea nonetheless. Despite the indignation of some Google Plus users at being ejected, Google has every right to set its own rules – those who dislike them can go elsewhere. The fact that “strong identity” should not be embedded into the fabric of the internet need not prevent individual enterprises from trying to cultivate it. For some companies, that means banning anonymity. Others could encourage users to disclose their full identities by rewarding them for doing so. Jeff Jarvis, a journalism professor, has argued for favouring “the comments of people who have the courage to stand behind their words with their names.” Those that introduce such incentives will hopefully cultivate an engaged and intelligent base of users and attract people alienated by the abuse of anonymity elsewhere. That is not the curtailment of freedom: it is the expression of it.

|