|

Corner Office

Asset Managers

Among the Worst-Governed Public Firms, Study Finds |

Even firms like BlackRock and State

Street that advocate for good governance score poorly for

accountability and long-termism in a new analysis.

June 22, 2018

|

|

Illustration by II |

Major shareholder activists such as

BlackRock and State Street speak out on governance issues at the

public companies they invest in. But do these asset managers actually

practice what they preach?

A new measure of governance quality

developed by researchers at Swiss business school

IMD suggests

the answer is no.

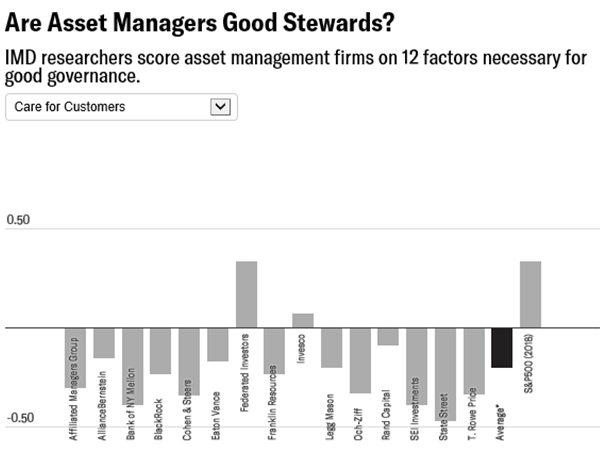

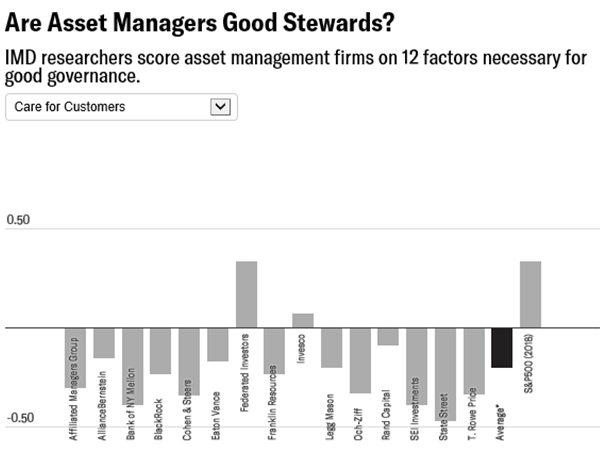

The stewardship rating grades listed

companies on qualities such as accountability, long-term focus, care

for customers, trustworthiness, and prudence. IMD professor Didier

Cossin created it with Stewardship Asia Centre chief executive Ong

Boon Hwee for their 2016 book, “Inspiring Stewardship.”

“A good business creates value to

society, rather than extracting it,” explained Cossin, who also serves

as director of the IMD Global Board Center and president of the

Stewardship Institute,

which he founded. “It’s a concept people generally understand, but

isn’t reflected in the market.”

Even standard environmental, social, and

governance metrics often fail to separate good stewards from bad,

Cossin argued. Commonly used governance criteria — such as whether a

board has independent directors — don’t necessarily translate to good

stewardship, and can be faked, he said.

To better capture how companies perform

in areas like risk management, alignment with stakeholders, and

innovation, Cossin used natural language analysis to rate companies

based on their own public statements, including 10-K reports and the

like.

A company that frequently used words

like “currently” or “quarterly” might rank worse on long-termism than

a company more often said things like “future” or “decade,” for

instance. Similarly, words like “litigation” and “petition” would

imply worse relationships with stakeholders than comments regarding

“communities” or “transparency.”

In one particularly telling example,

Wells Fargo — which came under fire last year for having created

millions of fake accounts — used the word “customer” only twice in its

2014 reports, according to Cossin.

When the stewardship language analysis

was applied to asset managers, the results were bleak.

“Asset managers are supposed to be well

stewarded, but they’re among the worst,” Cossin said.

Asset managers scored below the average

S&P 500 company in eleven out of twelve dimensions included in the

study: accountability, care for customers, harmony with stakeholders,

innovativeness, long-term focus, passion, positivity, proactiveness,

prudence, purposefulness, and trustworthiness. The only area in which

the average asset manager did better than the typical large public

company was identification, a measure of the sense of ownership and

identity associated with a company.

Even firms that have taken public

stances on issues like

climate change

and

board diversity generally

performed worse than the average S&P 500 company. BlackRock, in fact,

did worse across all 12 dimensions, though it came close to the

typical large-cap company on passion, or expressions of engagement.

Compared to other asset managers,

BlackRock scored well on measures of innovation, passion, positivity,

proactivity, prudence, and trustworthiness.

State Street, meanwhile, earned its

highest marks on identification, outperforming the average asset

manager as well as the broader S&P 500. The firm lagged the typical

large-cap company in every other category, but outscored its peer

average on innovation, passion, positivity, and prudence.

The best performing asset management

firm was T. Rowe Price. The Baltimore-based company outscored both its

peers and the average S&P 500 member on accountability,

identification, prudence, purposefulness, and trustworthiness.

Cossin

and his research partner Abraham Hongze Lu concluded that T. Rowe

Price benefited from being a “pure play” asset manager – in other

words, not having as many “distractions and conflicts” as multi-asset

managers.

These conflicts – such as simultaneously

trying to serve both company shareholders and investors in their funds

— can complicate governance for asset management firms, they

explained.

Governance problems correlated with

worse financial performance. Cossin said the public companies that

scored best on his stewardship rating exhibited less down-side risk,

with their stocks performing better in market downturns.

“Doing the right thing has the better

chance of making money,” he said.

xxx

|

*Average scores

refer to a peer group of 76 publicly-held asset managers and

custody banks.

|

|

© 2018 Institutional Investor LLC. |

|