BUSINESS

NEWS

JUNE 19, 2019 / 1:08 AM

Wall Street takes on

long-term care payouts as insurers balk at costs

David French

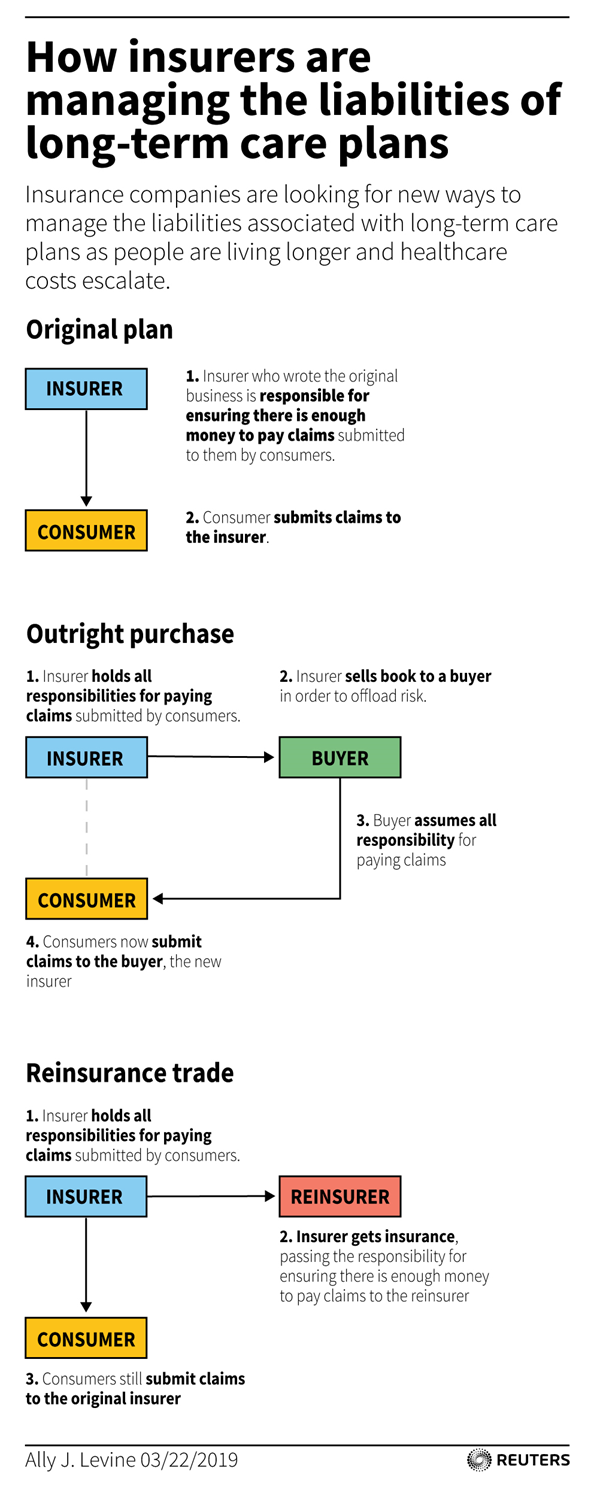

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Some

U.S. insurers are turning to Wall Street’s financial wizards for relief

from the liabilities of their long-term care (LTC) policies, posing a

challenge for regulators worried about how new industry players will

tackle the risks involved.

|

FILE PHOTO: A street sign is seen in

front of the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street in New York,

February 10, 2009. REUTERS/Eric Thayer |

These policies help support

the provision of care to those unable to handle everyday tasks, such as

bathing and cooking, by funding assisted living or nursing home

arrangements. Many have become financially toxic for insurers, because of

soaring healthcare costs and rising lifespans.

A few investment firms are

willing to take on these LTC contracts, betting they can invest the

premiums from the policies to generate strong enough returns to cover the

payouts, and even turn a tidy profit.

While these transactions

promise financial relief to insurers, they are not without risk. The LTC

liabilities can be big enough to weigh on even conglomerates such as

General Electric Co. If the premiums from the assumed LTC contracts are

invested poorly, there may be insufficient money to cover the payouts,

industry experts say.

“Some of those deals include

nontraditional actors, which we question with regard to their expertise

associated with the management of these liabilities, as well as the very

aggressive reserving and cash-flow assumptions,” said Anthony Beato, a

director at credit ratings agency Fitch Ratings.

Those at the forefront of

state insurance regulation paint a picture of the industry’s watchdogs

attempting to walk a fine line between the need to alleviate financial

pressure on insurers and policing risky deals.

“There is a trend toward

encouragement to make sure there is a functioning private LTC insurance

market to cope with the baby boomers’ needs,” Fred Andersen, chief life

actuary at Minnesota’s Department of Commerce, said of the general

regulatory attitude toward these deals.

At stake is the viability of

the LTC policies on which elderly and disabled people rely. Without

private insurance, they would be forced to pay for their own care or rely

on already-stretched state and federal programs such as Medicaid.

Around 12 million people in

the United States will need such assistance by the end of this decade,

according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This figure

is set to skyrocket as the number of retirees increases; Americans over 65

years old are projected to more than double to 98 million by 2060.

The LTC market has already

shrunk because of the financial strain facing insurers. Fewer than 70,000

new LTC policies were written in the United States in 2017, down from

372,000 in 2004, according to the most recent data from the National

Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). The average annual LTC

policy premium rose to $2,772 in 2015 from $1,677 in 2000, based on NAIC

data.

POLICIES

CHANGE HANDS

Two major LTC transactions

took place in the last 12 months, and insurance executives and dealmakers

say they expect more to happen this year.

Continental General

Insurance Company (CGIC), a subsidiary of hedge fund veteran Philip

Falcone’s HC2 Holdings Inc, completed the purchase of health insurer

Humana Inc’s $2.4 billion LTC business last August.

It was the second such deal

for CGIC, which also acquired the LTC business of American Financial Group

Inc in 2015.

In September, Wilton Re,

which is owned by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, reinsured the

LTC policies of CNO Financial Group Inc. This meant that CNO continued to

administer the policies, but Wilton Re took over the investment of the

premiums and guaranteed the payouts.

Humana and CNO had to pay

the financial firms $203 million and $825 million, respectively, to get

the LTC portfolios off their books.

Analysts say such one-off

charges are better for insurers than allowing LTC policies to drain their

finances. Fitch said in a report last October that many U.S. insurers with

LTC portfolios would need to allocate at least 10% more cash to reserves

covering these policies in 2019.

Prudential Financial Inc and

Unum Group were among the insurance firms that announced in 2018 they

needed to commit extra cash to fund future LTC liabilities. One insurer,

Penn Treaty, collapsed in 2017 under the weight of its LTC obligations.

General Electric, which said

last year it would take a $6.2 billion after-tax charge and set aside a

further $15 billion in reserves to help cover its LTC liabilities, is also

looking for a buyer for its LTC portfolio, Reuters has reported.

RISKY BETS

CNO’s first attempt to seek

relief from its LTC portfolio soured in 2016 following a reinsurance deal

with Beechwood Re, which was founded by two Wall Street veterans.

Beechwood subsequently

collapsed after investing some of the policy premiums in Platinum

Partners, a hedge fund that folded due to its risky bets and whose top

executives were indicted in a U.S. federal fraud probe in December 2016.

As a result, CNO was forced

to reabsorb the $550 million LTC portfolio and take a $53 million

after-tax charge.

U.S. state regulators tasked

with averting such failed deals are generally more focused on the reserves

the investment firms set aside, rather than how they invest the premiums

from the LTC policies, said Ann Frohman, founder of Frohman Law Office and

a former head of Nebraska’s Department of Insurance.

“In addition to current

requirements, one area of improvement would be having all states require

the stress-testing of investment assumptions on LTC portfolios against

financial crisis-type economic conditions,” Frohman said.

Some firms taking on the LTC

portfolios also invest in junk-rated corporate credit, which is more

susceptible to losses during an economic downturn, according to Fitch’s

Beato.

Wilton Re declined to

comment on how it invests LTC policy premiums, while a CGIC spokesman said

it focuses on generating higher yields from investment-grade assets.

Even if some insurers do not

place risky investment bets, regulators say they also have to watch out

for firms seeking to avoid paying out some claims to boost their

profitability.

“That is always a concern,”

said Pennsylvania’s insurance commissioner, Jessica Altman.

Reporting by David French in New

York; Editing by Greg Roumeliotis and Matthew Lewis

© 2019 Reuters. |