Corporate Board Member, January/February 2009 article

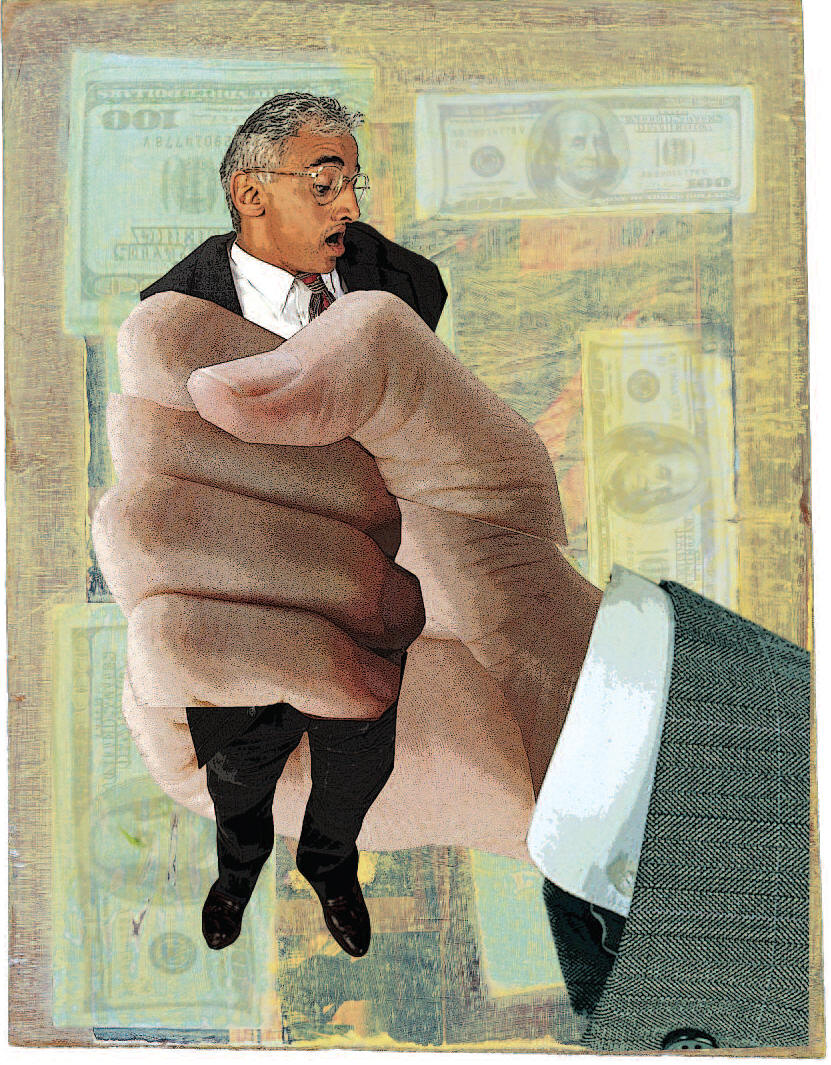

Here’s One Way to Get a Grip on CEO Pay

s there anything directors can actually do to moderate CEO pay? You bet. Internal pay equity does just that. It limits the top guy’s compensation to a multiple of the company’s four other top-paid executives, whose comp—like the CEO’s—is deconstructed in the proxy statement.

Among those that have imposed this ceiling are ConocoPhillips, DuPont, and Whole Foods Market Inc. Another is CPS Energy, a municipally owned utility in San Antonio, Texas. Until 2005, CPS’s board of trustees had used peer benchmarking to set the pay of CEO Milton B. Lee, continually ratcheting it up to the point that in 2005 he earned $548,803 in total compensation—a sum that put his comp in the 25th to 30th percentile of all CEOs, high for a municipal utility. Enough, said the board, turning to Mark Van Clieaf of MVC International, a consulting firm in Tampa, Florida, to look for other ways to do things. Van Clieaf soon discovered that the trustees were benchmarking CPS against a grab bag of far more complex energy, telecom, and Internet businesses. One socalled peer was IAC, the Internet company founded by Barry Diller, consistently one of the most highly paid executives in the U.S. What did the owner of Match.com have in common with a local utility? Not too much, obviously. “We felt we had to be fair, but what was fair?” says Stephen Hennigan, executive vice president of San Antonio Federal Credit Union, who was then outside chairman of CPS’s board (the job rotates among trustees) and head of the personnel committee that oversaw compensation. Hennigan, now 44, wanted another benchmark. Van Clieaf, a proponent of internal pay equity, urged the board to look at the pay multiples within the company, from the level of front-line manager on up through some eight layers of management to the CEO. The trustees discovered three things: The company had too many management layers, the productive managers were underpaid in light of what they actually did, and the CEO was earning nearly three times as much as his 13 direct reports. “We asked ourselves, how is the CEO’s work three times more complex to justify three times more pay than the next level down?” says Hennigan, who recently moved to the audit committee. The question not only opened up a discussion of strategy but also enabled the board to identify what it really needed from its CEO. The trustees wanted Lee to work at a higher level of innovation to prepare the company for potential competition over the next decade and to get his managers focused on energy efficiency and renewable energy sources like wind and solar power. To help the CEO carry out this new mission, CPS set out to restructure management, eliminating two levels to speed up decision-making. “It now took us 24 hours to respond to customers’ critical business needs, as opposed to 30 days,” says Aurora Geis, 43, senior credit officer at San Antonio Federal Credit Union, who took over as CPS’s personnel committee chair in 2008. At the same time, people were made accountable for these decisions, and their comp indicates that the utility is on track to realize significant savings from the restructuring. The CEO has fared well too. His total comp reached $680,000 in 2007. But the 35% raises of the two senior vice presidents who report to him reflect a reduction in Lee’s pay ratio, to a maximum of twice what they make. Lee, who could pocket as much as $734,000 for 2008, would probably be making more had the board stuck to peer benchmarking as a way to compensate him. But he’s happy. For one thing, he agreed to the new compensation system because it was part of a general reorganization he liked and was spearheading. “My job became more exciting,” he says. “I got out from under day-to-day operations, which are handled at the level below me now, and that freed me up to do the thinking about long-term strategy. I have the time to see how other companies are handling their businesses, and I work with my board to talk about strategy instead of the execution of strategy.” Lee, 61, notes that pay is seldom at the top of the list of what managers like about their jobs. “Maybe my pay could have gone up to a higher level under the old system,” he says, “but I’m setting up this organization for the future. And if I do it right, we’ll never have to do it again.” Could internal pay equity for the CEO and other top executives work at other companies? It’s certainly something board members, especially those on the comp committee, should be considering, along with benchmarking and pay for performance. But as Van Clieaf himself cautions, “Internal pay equity is not a governor to bring down CEO pay.” The guiding principle of pay equity is differential pay for differential work. That means the higher the level of management responsibility, the higher the level of valued-added work that should be expected from the managers. Says compensation consultant Frederic W. Cook, who runs his own firm in New York City: “Other executives don’t expect to be paid what the CEO is paid, but they do expect to be paid what they think their jobs are worth, what they think is fair in relation to what others are getting.” David Swinford, CEO of Pearl Meyer & Partners, a compensation consulting firm in New York City, agrees. “People take no pride in the fact that their CEO is the highest-paid in their industry,” he says. “But they are proud to be part of a team that is paid fairly.” It’s no secret that at too many companies, CEOs are hogging an increasing portion of the compensation pie set aside for top managers. In 2006, according to the most recent figures available from Equilar, which specializes in benchmarking executive compensation, the median multiple for CEOs of S&P 500 companies was 2.96 times the median pay packages for all other top managers identified in proxies, the socalled named executive officers, or NEOs. In the 1980s, according to a study of 300 of the largest corporations by the Federal Reserve Board, the ratio was 1.58. Alas, there is no clear-cut “right” multiple that boards can use as a template. “If you’re in the range of two times or three times for the CEO and the next four executives and somewhere around 100 times for the CEO and the average employee, you’re in the mainstream,” says Michael Kesner, a principal in the executive-compensation practice at Deloitte Consulting LLP. There is a feeling that anything more than a multiple of three between the CEO and the next layer of managers is too much. Moody’s Investors Service regards a ratio greater than three as a potential red flag indicating poor governance, which in turn can have an impact on the company’s debt rating. “In and of itself, a high ratio won’t affect the debt rating, but it’s one of the things we look at,” says Chris Plath, assistant vice president for governance at the rating agency. The Securities and Exchange Commission would like boards to disclose the extent to which they use internal pay equity ratios in setting CEO pay, although the agency has neither made that mandatory nor said anything about what ratio might be appropriate. Activist investors also stop shy of defining what is or isn’t appropriate by means of multiples. Institutional Shareholder Services says it weighs internal pay disparity—something it defines as “excessive differential between CEO total pay and that of the highest-paid named executive officer”—when deciding whether to recommend that shareholders vote against or withhold their votes from compensation committee members and even entire boards. That’s not the only factor, however. “I do not believe we’ve ever recommended against a director purely due to internal pay equity issues,” says Carol Bowie, who leads ISS’s governance institute. How much is “excessive?” “We don’t have any hard-and-fast policy on that. We’re looking at it on a case-by-case basis,” Bowie says. Some investors are demanding to know the degree to which companies weigh pay equity multiples in setting executive compensation. Denise Nappier, treasurer of Connecticut and principal fiduciary of a state employee pension fund with assets of $25 billion, filed shareholder resolutions against retailer Abercrombie & Fitch and grocery chain Supervalu in January 2008, calling on them to disclose “the role of internal pay equity considerations in the process of setting compensation for the CEO and the NEOs.” Abercrombie & Fitch’s 2007 proxy showed that CEO Michael Jeffries earned 6.16 times more than the next highest-paid officer. At Supervalu, chairman and CEO Jeffrey Noddle outearned the next-highest-paid executive by a multiple of 3.98. “Some pay gaps were troubling. We were interested in having them explained,” says Meredith Miller, Connecticut’s assistant treasurer for policy. Nappier settled with the two companies after they agreed to disclose more information in their 2008 proxies. They did so. Both outfits reduced the CEO’s comp and also increased what they paid those reporting to him, bringing the multiples to a more acceptable range of three. Abercrombie’s 11-page 2008 compensation discussion and analysis made glancing reference to internal pay equity but went into considerable detail about how the company had arrived at the pay packages for its top officers. Supervalu’s 2008 proxy covered much the same ground in a 17-page explanation. The comp committee added that it “will review periodically the relationship of target compensation levels for each named executive officer relative to the compensation target for Mr. Noddle.” Nappier withdrew her suits, and Miller says the two companies “responded very well to our concerns. They signaled the new compensation trend of companies’ being willing to roll up their sleeves and talk about how they compensate people.” At most companies, market data and individual performance are what drive CEO compensation, according to consultant Michael Kesner. He estimates that only about 15 of the S&P 500 companies apply internal pay ratios. Whole Foods has a system of its own, using only cash salaries and incentives paid in cash in its ratio. It also effectively caps CEO John Mackey’s comp at 19 times the average annual wage the company pays its full-time employees. In 2007 Mackey, a co-founder of the company, came in well below that, having voluntarily reduced his salary to $1 a year (“I am now 53 years old, and I have reached a place in my life where I no longer want to work for money but simply for the joy of work itself,” he announced). He took no bonus or stock awards that year either, and didn’t appear to receive any options. He did collect $297 in the form of a company contribution to his 401(k). An examination of how internal pay works also highlights any problems a company might have with management succession. When the CEO regularly earns more than three times as much as the next level of managers, “it does suggest there is no one else in line,” says compensation consultant Donald Delves of the Delves Group in Chicago. Worse, Pearl Meyer’s David Swinford thinks a big disparity between the CEO’s comp and everybody else’s can be what he calls “demotivational.” The company is obviously a one-man band instead of a team—how else could the board justify that compensation? Consultant Mark Van Clieaf recalls a client whose CEO was paid $8 million while the executives at the next level down were getting about $1.5 million each. When the consultant looked into the responsibilities of the CEO and the people under him, he discovered that the CEO was allowed to spend $75 million a year without board authorization, but his direct reports each had a limit of $3 million. “So maybe you’d conclude that the CEO was making all the decisions,” Van Clieaf says. “And we found out that he was making all the key ones.” The board realized from this discovery that none of the senior vice presidents it was considering as a future chief executive really had the experience or the ability to take on the top job. But often senior VPs do include potential CEOs, and in their case huge pay disparities may send an unspoken message that the board has no interest in grooming them for the next step up. “If pay is a demonstration of value, a big gap suggests that the second-tier managers aren’t as highly valued as the CEO,” says Carol Bowie of ISS. What does that say about the company’s succession pipeline? Come the day when the one-man band gets hit by the proverbial bus, the board will be forced to buy a new CEO rather than promote one, with all that implies for compensation costs. “The biggest megaphone a company has to communicate that someone is valued is the pay system,” says Jeffrey Hyman, a consultant with Exequity who works out of Wilton, Connecticut. “If you as the No. 2 earn half of what the CEO earns, you would feel pretty good about where you are.” Looking at the internal pay equity ratio forces directors to focus more on the team at the top, whether or not its members are in line for the CEO position. But pay equity also has to be examined within the context of the company’s industry. Directors need to be aware of what competitors are paying, since a company can have a perfectly equitable system within its own ranks but still be under- or overpaying by the industry standard. Whole Foods found itself in the former camp. It raised its salary cap in 2006 from 14 times the company’s average annual wage to today’s 19 times to prevent key managers from being poached by other companies offering fatter pay. Proponents of equity pay love to cite how DuPont got a handle on CEO comp in 1990—and how the CEO himself initiated the solution. The company has been living with this form of compensation since then-CEO Edgar S. Woolard decided that he would stop chasing surveys and limit his pay to 1.5 times what the company paid its executive vice presidents. Woolard chose this group because they ran DuPont’s businesses and made the decisions on prices and new products, albeit with his guidance. Today DuPont keeps its CEO in the range of two to three times the average of all the company’s executive officers, not just the top four mentioned in the proxy. “The reason why compensation committees should be interested in internal pay equity is to give them a second perspective on how to pay people—not just the market perspective,” says consultant Frederic Cook. “It’s a second data point.” It also reinforces the idea that there is a team at the top of the company—and that every team member is accountable to shareholders for how well the company fares.

|