|

Why 'say on pay' won't

work

Reformers are counting on

shareholders to rein in compensation. But big investors seem inclined to

remain quiet and preserve the status quo.

Colin

Barr, senior writer

November 16, 2009:

5:04 AM ET

| |

Sen. Chris Dodd

would give shareholders a nonbinding vote on executive pay. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

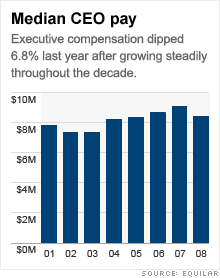

NEW YORK (Fortune) -- Waiting for

investors to slam the breaks on runaway executive pay? Don't hold your

breath. Although Congress may give shareholders more of a say on pay soon,

big money managers seem content to keep their mouths shut.

Senate Banking Committee Chairman

Chris Dodd, D.-Conn., unveiled a financial reform plan this month that would

give investors in public companies an advisory vote on pay policies starting

in 2011.

It's the latest boost for

say-on-pay plans, which reformers have been pushing in recent years with

some notable support. The idea is that shareholders, as the owners of public

companies and the natural guardians of the corporate purse, will pressure

directors to hold the line on pay -- particularly at underperforming firms.

President Obama has backed making

say on pay mandatory. More than two dozen companies, including Verizon and

Microsoft, have adopted the plans.

Say on pay seems particularly

appealing now, as Wall Street firms prepare to pay out huge bonuses at a

time of high unemployment and massive taxpayer-funded subsidies for the

economy.

But there's a catch. The biggest

investors -- institutions such as mutual funds and pension funds that hold

more than half of all shares -- have shown little interest in playing pay

watchdog. And it's not clear that will change even if the government

mandates say on pay as part of the financial reform taking shape in

Washington.

"We just haven't seen a huge

amount of effort being put out by institutional shareholders to affect

compensation levels," said Bernard Black, a law professor at the University

of Texas. "Whether it's because they don't mind the pay practices or because

the money managers are making millions themselves, you don't see them

jumping up and down."

Black notes that institutions

rarely try to elect their own candidates to boards or take other actions

that might be classified as shareholder activism. But critics go further.

A recent study co-sponsored by a

union pension fund and a top governance firm dubs many of the biggest mutual

fund firms -- including Ameriprise, AllianceBernstein, Barclays and MFS --

as "pay enablers" for supporting management pay proposals and opposing those

by shareholders.

The report, co-sponsored by the

Corporate Library and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal

Employees (AFSCME), chastised the funds for "failing to use their voting

power in ways that would limit compensation excesses."

MFS disagreed with these

findings. The closely held Boston-based firm said the study "did not truly

reflect the firm's position on executive compensation." The fund firm added

that since 2007, it "has determined excessive executive compensation at over

70 issuers and has not supported over 200 directors due to excessive

executive compensation concerns."

MFS hasn't been a fixture on the

pay enabler list. But Ameriprise, AllianceBernstein and Barclays have made

it each of the last four years, the report said.

These firms didn't respond to

requests for comment, but Richard Ferlauto, who directs corporate governance

and pension investment at AFSCME, said it's clear they aren't looking out

for their customers.

"The funds have an obligation to

their investors to monitor the performance and the practices of their

holdings," he said. "Had there been more rigor on the part of these funds in

reviewing their investments, some of the worst problems of this downturn

could have been avoided."

Eleanor Bloxham, who runs the

Value Alliance corporate governance firm in Westerville, Ohio, said big

shareholders don't tend to take an active role in overseeing pay because the

industry is rife with conflicts of interest.

"Everyone is in the same boat in

the financial services business, as suppliers and customers and 401(k)

holders," she said. "There is no great will to stand up."

By the same token, researchers

say cost-benefit analyses often make activism less attractive to

institutional shareholders. Big firms often hold thousands of stocks in

giant diversified portfolios, making intensive monitoring a major chore.

"I'm not one who believes

corporate governance will solve our problems," said Margaret Blair, a law

professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. "Shareholders are not

in position to address the main problem, which is the incentives we are

giving to management."

Still, for all its limitations,

say on pay is widely acknowledged to be better than one oft-mentioned

alternative -- greater pay regulation.

"At most, say on pay might bring

down some of the biggest paychecks. But I don't see how that's such a great

threat to capitalism," Black said.

|

©

2009 Cable News Network. A Time Warner Company ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. |

|