APRIL 18, 2016

The Risk in No-Risk Stock Buybacks

Many companies are now struggling with falling stock shares: Do they

use buybacks to placate shareholders even at the risk of making a

lousy investment?

By S.L. Mintz

|

|

IMAGE CREDIT: KIMBERLY LUM |

The

Wal-Mart Stores brand advertises nothing if not low prices for

consumers. Last October that applied as well to the giant retailer’s

stock, which had sagged a third below the price from a few months

earlier — one everyday low price situation the company felt it needed

to fix. Wal-Mart responded by, among other steps, authorizing a $20

billion program to buy back its shares.

Bentonville, Arkansas–based Wal-Mart intends to complete the buybacks

over the next two years, shrinking its current market capitalization

of $216 billion by around 10 percent. Its buyback announcement topped

all others in 2015, with the exception of the $50 billion

stock-repurchase program that Fairfield, Connecticut, industrial

conglomerate General Electric unveiled in April, when stocks were

still rising.

That makes Wal-Mart something of an outlier. Across the Standard &

Poor’s 500, buyback announcements and repurchasing activity eased in

the final months of 2015, when stocks slid amid mounting volatility.

Institutional Investor’s most recent Corporate Buyback

Scorecard, created by

Fortuna Advisors using data from Capital IQ, judges buyback

programs over eight quarters. The latest Scorecard ranks buyback

return on investment at 299 companies where repurchases of stock

reduced market capitalization by 4 percent or more, and, in a few

instances, exceeded $1 billion, two thresholds for materiality.

The Buyback Scorecard, which Institutional Investor has been

publishing since the

first quarter of 2013, provides investors with a set of metrics to

evaluate corporate buyback programs. The core measure, buyback ROI,

estimates the internal rate of return of cash flow associated with

buybacks. Cash flow includes money paid to investors who sold their

shares; the value of undistributed dividends; and an estimate of the

value of the accumulated repurchased shares.

Low buyback ROI is not necessarily an indictment

of management, whose job it is to juggle a variety of cash flows to

generate longer-term growth. But buyback ROI does enable investors to

weigh the merits of earmarking billions of dollars in capital to

repurchase shares.

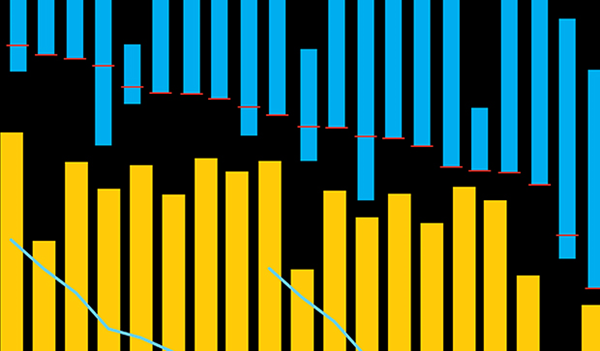

The evidence from buybacks over the past eight quarters ending in the

fourth quarter of 2015 indicates that buyback programs have lost some

luster. Median ROI posts a seventh successive decline on the latest

Scorecard, to 4.2 percent, from 29.6 percent two years ago. Part of

that decline stems from subpar execution in buyback effectiveness, a

metric that measures the gap between buyback ROI and annualized total

shareholder returns. Positive buyback effectiveness indicates that

companies repurchased shares ahead of rising price trends. When

buyback ROI is negative, however, companies bought back shares only to

discover stock prices falling. Access to internal data on daily

repurchase activity can refine Scorecard results.

The overall effectiveness of repurchase programs peaked on

2013’s second-quarter Scorecard, when buyback ROI surpassed

underlying shareholder return by nearly 10 percent. The relationship

reversed in mid-2014, with buyback ROI falling short of shareholder

return. On the current Scorecard buyback effectiveness is down to –5

percent, the second-lowest since we launched the Scorecard.

If

pressed to validate its buyback execution, Wal-Mart might have a tough

time right now. The retailer’s buyback ROI is running at –21.2

percent, trailing 260 other companies, including five of its six peers

in the Food and Staples Retailing sector. Only Whole Foods Market,

headquartered in Austin, Texas, fared worse. A four-year window

doesn’t improve the view. Wal-Mart tumbles 49 places from its

Scorecard ranking two years ago, which reflected buybacks in 2012 and

2013. Wal-Mart’s buyback effectiveness in the latest period is at

–12.9 percent. Poor timing of buybacks did more damage to shareholder

wealth than the decline in the underlying shares.

What’s more, the impressive $20 billion figure of Wal-Mart’s newest

buyback program requires an asterisk. That amount includes nearly $9

billion rolled over from the $15 billion buyback program announced two

years ago. At that time, Wal-Mart’s chief financial officer, Charles

Holley, touted strong cash flow and pride in “our long history of

returning value to shareholders through the combination of dividends

and share repurchases.”

Taking two bows for the same buyback undermines investor faith that

companies will execute as promised. And it may erode a company’s

ability to signal confidence, a prime motive for many buybacks. “The

market is smart,” says John Tomlinson, head of consumer research at

New York–based ITG Investment Research. “Companies can’t continue to

say they’re going to buy back stock and not do it.”

Double-dipping on buybacks is not unique to Wal-Mart. In December,

Chicago aerospace giant Boeing Co. scrapped a $12 billion buyback

authorization from 2014 with $5.3 billion still unused and advertised

a new $14 billion repurchase plan. In February, American International

Group, the New York–based insurer that was at the epicenter of the

financial crisis, authorized $5 billion on top of a $10.7 billion

repurchase authorization with nearly $6 billion still untouched.

Wal-Mart might not want to publicize the counterintuitive reality that

by not repurchasing those shares the retailer actually preserved value

for shareholders; the business would have lost more if it had spent

all the money. Even so, Wal-Mart buyback ROI on the current Scorecard

underperforms total shareholder return by nearly 13 percentage points.

Tomlinson sees no legerdemain at work. Market forces, he says,

compelled Wal-Mart to step up as it did. Authorizing more buybacks

suggested that its robust cash flow could support huge demands.

“[Wal-Mart] wanted to assure the shareholder base they were not

running away from their capital-allocation strategy,” says Tomlinson,

especially in terms of returning capital to investors. Investors

responded, if cautiously. By early March, shares traded at a 10

percent premium to the price just before the buyback was announced —

commensurate with the expected impact of the program.

Elsewhere in the rankings the largest independent refiner and marketer

of oil in the U.S. proves that buyback ROI can flourish even in

beleaguered sectors. San Antonio, Texas–based Tesoro Corp. garners

first place on the current Scorecard. Falling oil prices have fueled

big profits at refiners. Tesoro delivered buyback ROI of 57.1 percent

with buyback effectiveness of 7.1 percent. Only Tesoro boasts buyback

ROI over 50 percent, while seven companies surpassed 40 percent, and

11 were above 30 percent.

No. 3 O’Reilly Automotive, based in Springfield, Missouri, also put

buybacks to good use. The automotive retailer authorized $5 billion in

buybacks in January 2011 and subsequently added $500 million to that

program. “When we look at buying stock back, we look at what we think

the long-term discounted cash flow value is and set our targets that

way,” CFO Tom McFall told analysts in August 2015.

During the conference call McFall credited buybacks in part to

unexpected performance. Faster-than-anticipated growth attracted

suppliers to finance inventory. The resulting cash flow prompted

O’Reilly to find ways to maximize the return to shareholders. “To date

that’s been repurchasing shares,” McFall said.

UBS analyst Michael Lasser noted that the only piece of O’Reilly that

was not working to its potential was the balance sheet and pressed

McFall on buyback execution. “How much we repurchase during a quarter

is a portion of our long-term plan,” McFall replied, but cash flow and

market conditions decide the pace: “We really look at buybacks as call

to call.” Early in 2015 “we were in a dark period ... and we bought

back not very many shares.” A month later, when cash flow picked up,

O’Reilly revved up its buybacks.

Lasser applauds the strategy: “O’Reilly has produced fantastic

operating results while enhancing the return for shareholders by

consistently buying back their stock.”

One of the Scorecard’s biggest losers this quarter operates in the

pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and life sciences sector: St.

Louis–based Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Stock repurchased by the

company surrendered more than half its value, even as annualized total

shareholder return produced a 19 percent gain.

Houston-based Quanta Services, which provides construction,

maintenance and technology services, retired 52.5 percent of its

market capitalization — more than any other company in the current

Scorecard.

Quanta CEO James O’Neil described the final tranche, a $1.25 billion

buyback, during the second-quarter conference call with the zest that

often accompanies such announcements. “This is by far the largest

share-repurchase authorization in Quanta’s history,” he said. “This

action reflects our commitment to creating shareholder value and our

ongoing confidence in the longer-term outlook for our business.”

The final accounting on Quanta’s buyback ROI awaits expiration of its

accelerated repurchase agreement, when the initial price per share,

using the volume-weighted average pricing before the buyback began,

will be adjusted. That adjustment, or true-up, reconciles the sum

earmarked for the buyback with the volume-weighted average price per

share over the course of the buyback.

Like many companies, Quanta has seen its stock fall. A falling stock

price provides one benefit — it allows cash allocations to repurchase

more shares. However, it all but guarantees negative buyback ROI. In

296th place overall, Quanta underperformed 30 of 32 companies in

buyback ROI in the Capital Goods sector. The sector generated a median

buyback ROI of 1.6 percent, whereas Quanta posted –42.6 percent and

lagged shareholder return on its stock by 33 percentage points,

subject to the true-up.

Quanta investor relations chief Kip Rupp urges a wait-and-see attitude

before judging a buyback program that was designed to pass to

shareholders a windfall from the sale of a business unit. “We had sold

off Sunesys and had $800 million in cash come in the door,” Rupp says.

“We did determine that our stock was attractive and that this was the

best use of capital for shareholders.”

Senior analyst Daniel Mannes at Nashville, Tennessee–based Avondale

Partners agrees. “There was not an easily identifiable better use of

proceeds given the size,” says Mannes. A special dividend might send

the wrong signal to growth-oriented investors, and the infusion would

swamp capital expenditures. If you want to nitpick, acknowledges

Mannes, Quanta might not have launched a buyback program had it known

that the stock would peak in June and then fall. “It’s not wrong,”

Mannes says, “but you could certainly quibble with the timing.”

One way to identify companies that have risen or fallen the most in

the Scorecard rankings is to look back at successive two-year windows.

For instance, Raleigh, North Carolina–based open-source software

developer Red Hat generated buyback ROI in 2012 and 2013 of –8

percent, only slightly better than its anemic buyback effectiveness.

Of 261 companies on that Scorecard, Red Hat landed at No. 254 in

buyback ROI.

However, following an accelerated share-repurchase program that

retired 6 million shares at an average price of $56.47, Red Hat’s

buyback ROI rose to 31.2 percent on the current Scorecard, placing it

among the top 20 companies. Red Hat’s shares hit a high of $83.65 on

December 30, then slipped into the $60s by early March during the

brutal early-2016 market. Reclaiming that share price high will be a

challenge, say analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch: “We believe

that the stock achieving high end of historical 25 times free cash

flow multiple will be hampered by secular concern,” BofA Merrill

reported in February.

Buybacks don’t exist in a vacuum. The Scorecard allows investors to

scrutinize buyback programs through several lenses. “Before buyback

ROI, there was no return-based metric for comparing buybacks to

allocations like M&A, capital expenditures or R&D,” says Fortuna CEO

Gregory Milano. “Buyback ROI allows us to look back at a company’s

track record and see if they’ve earned adequate returns.”

Among 24 sectors Technology Hardware and Equipment repurchased the

most stock. These companies sank $150 billion into buybacks, three

times the median for all sectors. Their collective buyback ROI of 7.9

percent, however, trails those of ten sectors, led by Consumer

Services and Consumer Durables and Apparel, which tie with median

buyback ROIs of 17.2 percent. Utilities comes in last, with a –17

percent in buyback ROI, offset by the fact that the sector had the

lowest volume of buybacks of any industry beside Real Estate.

Quintile groupings can also provide benchmarks for evaluating

buybacks. Investors can compare companies in five tranches of buyback

ROI, median dollar total buybacks and total dollar buybacks as a

percentage of market capitalization. For instance, that last metric,

total dollar buybacks as a percentage of market cap, shows the buyback

ROI that companies were able to deliver based on how much market cap

they eliminated. The top tranche reduced market cap by over 20

percent. These aggressive buybacks produced, however, the lowest

median buyback ROI at –14.3 percent. Companies in the middle tranche

retired just under 8 percent of market cap and enjoyed median buyback

ROI of 10.1 percent. The bottom tranche retired 4.2 percent of market

capital, with median buyback ROI at 7.5 percent.

Senior analyst Michael Halloran at Robert W. Baird in Milwaukee argues

the widely held notion that stock repurchases are exempt from judgment

applied to other uses of shareholders’ capital. “Buybacks have nothing

to do with the destruction of value,” he insists.

That’s good news for Flowserve Corp., an Irving, Texas–based maker of

industrial pumps, valves and seals that Halloran follows. In terms of

buyback ROI, Flowserve sits right above Quanta Services in the

basement of the Capital Goods sector, with a buyback ROI of –28

percent. Another investment with a negative ROI over two years might

irk investors, but, said Flowserve CEO Mark Blinn last October,

“Returning capital to shareholders was another key priority during the

quarter.”

At

Flowserve, Halloran sees a balance sheet in good shape, a suitable

amount earmarked for accelerated share repurchase and ample free cash

flow available for capital expenditures, M&A or capital returns to

shareholders. “I’m not going to ding them for a consistent policy when

over time it will probably prove to be okay,” he says. His current

rating on the stock is neutral.

However, Halloran also admits that buybacks might allow managers to

punt instead of taking the kind of risk that spurs growth. “I

certainly suspect that is part of the discussion,” he says, noting

that boards insist on hitting a lot of boxes before material

transactions can proceed. For shareholders, as the Scorecard reveals,

no-risk buybacks pose risk, too.

|

© 2016 Institutional Investor LLC. |

|