|

THE WALL STREET

JOURNAL. |

Business

Business

GM Sets Buyback, Placating Activists

Nation’s

largest car maker is latest to feel pressure by hedge funds

critical of management spending

GM Chief Executive Mary Barra agreed to a $5 billion share

buyback and spending on dividends amid pressures from prominent

investors, balancing the auto maker’s need to boost spending on

new vehicles and maintain its investment grade rating. PHOTO: BLOOMBERG NEWS |

By

Vipal Monga and

David Benoit

Updated March 9, 2015 10:22 p.m. ET

General Motors

Co. on Monday became the latest company to return

billions of dollars to shareholders amid tussles with investors over

how to better allocate corporate cash.

Facing a potentially

contentious fight over a board seat and a larger buyback, the car

maker tried to walk the line between placating big investors and

spending more on its future.

GM disclosed a $5 billion

stock repurchase, a sum that comes on top of a previously announced

dividend increase, and an additional $9 billion it will spend this

year to improve brands including Cadillac, boost fuel efficiency and

develop electric and driverless cars, among other things.

GM’s decision highlights a

dilemma facing many companies as activists cement their toehold in

boardrooms: Who is better at determining the appropriate use of cash

as corporate balances grow?

Some data suggest

activists discourage companies from investing in their businesses,

something many activists would readily admit, citing wasteful

spending.

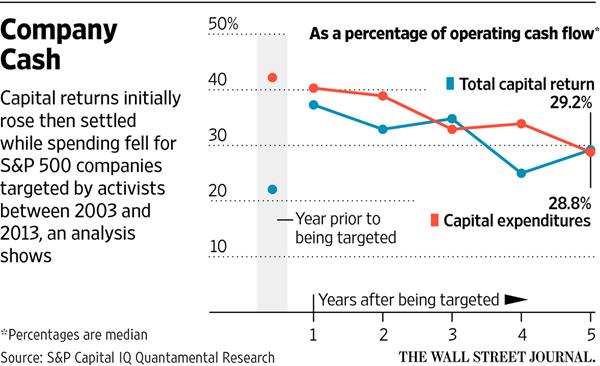

Companies in the S&P 500

targeted by activists between 2003 and 2013 reduced their spending on

plants, equipment and research to 29% of their cash from operations in

the five years after activists bought their shares from a median of

42%, according to an analysis conducted for The Wall Street Journal by

S&P Capital IQ’s Quantamental Research unit.

That compares with the

much smaller drop to 25% from 27% for nontargeted companies over the

same period.

Meantime, corporations

targeted by activists boosted dividends and stock repurchases to a

median of 37% of operating cash flow in the first year after being

approached by activists, from 22%. S&P 500 companies that weren’t

targeted by activists showed a 10-point increase, to 36%.

“Companies only have a

finite amount of cash,” said David Pope, a managing director at S&P

Capital IQ. “If they spend it on shareholder returns, there is less

cash to spend on everything else.”

GM made its buyback

decision after top officials determined its $25 billion in cash was

more than enough to fulfill spending plans and handle uncertainties

like the federal investigation into a botched ignition-switch recall.

People familiar with the decision said a buyback already was under

consideration and investor talks sped it up.

| |

‘Companies have a finite amount of cash...’

—David Pope, S&P Capital IQ

|

“We believe an initial $5

billion share buyback is good for our owners because we cannot earn

better returns by investing that cash in the business at this time,”

GM finance chief Chuck Stevens said on a conference call.

Separately, on Tuesday,

some large investors and corporate chiefs are gathering in New York to

debate the social and economic impact of rising shareholder pressure.

The nation’s largest auto

maker had come under fire from Harry Wilson, a former architect of

GM’s federal bailout, who wanted an $8 billion buyback and had the

backing of four hedge funds in his bid to get a seat on the company’s

board.

“Capital allocation is an

underappreciated discipline,” Mr. Wilson said in an interview on

Monday.

“When activism works well,

one of the things it does is try to create a disciplined framework

around this decision.”

GM had said last month

that it would discuss more capital returns later this year.

The company was waiting

for clarity around any fine the Justice Department might levy as well

as other litigation that may result from a massive recall due to

faulty ignition switches, the people said.

Mr. Wilson and the funds

have dropped the request for a board seat in light of the buyback and

GM’s pledge to better explain its spending and goals.

GM stock rose 3.1% to

$37.66 in 4 p.m. New York Stock Exchange trading on Monday.

Not all investors were

excited. James Potkul, a Parsippany, N.J., investment manager who

controls about 10,000 GM shares, said the auto maker should instead

marshal its cash to protect against uncertainties. “Are they worried

about a downturn? They should be,” he said. “These companies can burn

cash pretty badly when a downturn comes.”

How and when to use

capital will be the topic of debate when the group of prominent

investors and executives calling itself Focusing Capital on the Long

Term meets in New York.

As a sign of the issue’s

weight, U.S. Treasury Secretary

Jacob Lew is expected to discuss

how public policy can support the goals of the group’s members,

including chief executives such as

BlackRock Inc. ’s

Laurence Fink ,

Unilever PLC’s

Paul Polman and

Barclays PLC Chairman Sir David

Walker.

Elliott Management Corp.,

a New York-based hedge fund, last year started criticizing

networking-equipment manufacturer

Juniper Networks Inc. for

spending $7 billion on acquisitions and nearly $8 billion in research

and development while its stock price greatly underperformed the

Nasdaq Composite Index since the

company’s 1999 initial public offering.

Last year, after settling

with Elliott to change the board, Juniper cut spending and repurchased

$2.3 billion of stock. It plans to buy back almost $2 billion more

through 2016.

The company paid its

first-ever dividend and borrowed money to fund some of the returns.

“The Juniper share

repurchase and cost-cutting efforts are the largest contributor to the

stock staying stable,” said

Scott Thompson , an analyst with

Wedbush Securities.

At the same time, he

warned that continued cuts could eventually hamper Juniper’s ability

to keep pace with innovation in the industry.

Some efforts haven’t

garnered the same praise. In early 2012, New York investment firm

Clinton Group Inc. took a stake in teen fashion retailer

Wet Seal Inc. and began urging a

share buyback. By February 2013, the company disclosed it was cutting

jobs and expenses and would repurchase $25 million of stock after

appointing four Clinton representatives to its board.

This January, Wet Seal

closed two-thirds of its stores and filed for bankruptcy protection.

In court documents,

executives cited a broader drag on teen retailers as well as missteps

that alienated core customers. People familiar with the bankruptcy say

that in hindsight the buyback was a bad decision.

“If we had rewound and

said they hadn’t done the buyback, that would have given them

substantially more flexibility,” said Jeff Van Sinderen, an analyst at

B. Riley & Co. “In those situations, $25 million dollars can go a long

way.”

—Mike Spector contributed

to this article.

Write to

Vipal Monga at

vipal.monga@wsj.com and David

Benoit at

david.benoit@wsj.com

|