Business Day

Valeant Shows the

Perils of Fantasy Numbers

OCT.

30, 2015

|

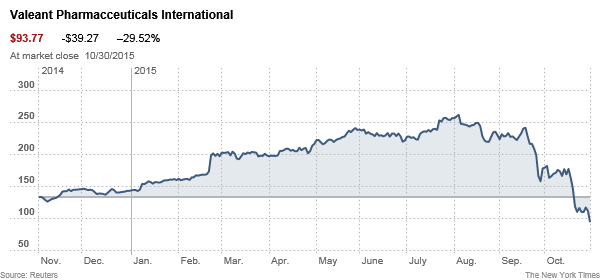

Valeant's market value has fallen

by more than $50 billion since August. Credit Lucas

Jackson/Reuters.

Credit Lucas Jackson/Reuters

|

Investors often say they learn more from investment losers than from

winners. That suggests that Valeant, the beleaguered pharmaceutical

company whose market value has fallen by almost $60 billion since

August, offers a bounty of teaching moments.

Let’s

start with the perils of relying on earnings forecasts and stock

valuations based on fantasy rather than reality. Such a reliance may

have lulled some recent investors into believing they were paying a

small premium to own Valeant shares when in actuality it was costing

them the moon. (The stock is still a winner for those who bought

shares before the autumn of 2013.)

| |

Fair Game

A

column from Gretchen Morgenson examining the world of finance

and its impact on investors, workers and families

See More »

|

| |

|

Valeant is among a growing number of companies that regularly present

two types of financial results: those that adhere to generally

accepted accounting principles, and those that help executives put the

best spin on their operations.

In accounting

parlance, such adjusted figures — which exclude certain costs from calculations

of a company’s earnings — are known as pro forma or non-GAAP numbers. But let’s

call them what they really are: a false construct.

Valeant is among

a growing number of companies that regularly present two types of financial

results: those that adhere to generally accepted accounting principles, and

those that help executives put the best spin on their operations.

In accounting

parlance, such adjusted figures — which exclude certain costs from calculations

of a company’s earnings — are known as pro forma or non-GAAP numbers. But let’s

call them what they really are: a false construct.

Part of the

problem with these adjustments lies in the freedom companies have to choose

which costs they want to strip out. One company may exclude stock compensation

costs from its earnings calculations while another in the same industry does

not. That makes it difficult to compare the two companies’ operations.

The tide of

companies making up their own earnings calculations is rising, said Jack

Ciesielski, publisher of

The Analyst’s Accounting Observer. In a

recent report, he noted that 334 companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock

index reported non-GAAP earnings last year, up from 232 such companies in 2009.

The dollar amount of cost adjustments made to those companies’ profits totaled

$132 billion last year, more than double the amount in 2009.

“There is a lot

more of this going on,” Mr. Ciesielski said in an interview. “The companies are

really pushing it.”

This creativity

is common practice in the pharmaceutical industry, so Valeant is certainly not

atypical. But the difference between the company’s real earnings and its

adjusted numbers is far greater than it is for its large competitors, making

Valeant a prime example of this problem.

In

news releases, Valeant executives

are careful to include their results under accounting rules. But these

communications tend to focus more on the company’s primary

hand-tailored figure — what it calls “cash E.P.S.” When providing

forecasts, for example, the company supplies only pro forma numbers.

Valeant strips out a laundry list of expenses from its revenue,

including those related to stock-based compensation, legal settlements

and costs associated with restructuring and acquisitions.

Most

significant, perhaps, for Valeant are costs related to acquisitions. Generally

accepted accounting principles require companies to recognize over time the

diminishing value of intangible assets they acquire when buying another company

— or amortization. Valeant excludes those costs.

At Valeant, an

acquisitive company, this is a big number. This year alone, Valeant has paid $15

billion for six deals in which terms were disclosed.

Excluding

acquisition-related costs from its pro forma figures, including amortization,

makes the company look far more profitable than it is.

The company says

it publishes pro forma figures to provide investors with “a meaningful,

consistent comparison of the company’s core operating results and trends for the

periods presented.” Valeant goes into detail on the expenses it is excluding, so

diligent investors can do their own analyses.

A spokeswoman

for the company declined to comment further.

Valeant took

another blow on Thursday when the nation’s three largest drug benefit managers

said they would stop doing business with a pharmacy that sold Valeant products.

The hedge fund manager William A. Ackman, who is one of Valeant’s biggest

stockholders, defended the company in a marathon three-hour conference call on

Friday, yet its stock continued to plummet.

Looking at

Valeant’s real earnings compared with its make-believe ones exposes an enormous

gulf. Under generally accepted accounting principles, the company earned $912.2

million in 2014. But Valeant’s preferred calculation showed “cash” earnings of

$2.85 billion last year. That gap is far wider than at other pharmaceutical

companies presenting adjusted figures.

It’s easier to

justify paying up for a stock when you’re relying on ersatz results. Valeant’s

shares, at their peak of $262, were trading at 98 times 2014 earnings. Set

against the fantasy figures, though, the stock carried a multiple of just 31

times. Not a bargain, perhaps, but also not insane.

Valeant’s History of Deal Making

The drug company is known for

growing through acquisitions and cutting costs.

-

BIOVAIL

The drug company was created in a merger of Biovail of Canada

and a predecessor company based in Aliso Viejo, Calif.

(2010)

-

CEPHALON

The biopharmaceutical company

rejected a bid from Valeant

as opportunistic and too low. (2011)

-

MEDICIS

Valeant agreed to buy the dermatological drug company for

about $2.6 billion. (2012)

-

ACTAVIS

Merger talks fell through after a number of concerns from the

target company’s directors, including the size of the deal

premium. (2013)

-

BAUSCH & LOMB

The eye care company sold itself for about $8.7 billion,

sidestepping an I.P.O. (2013)

-

ALLERGAN

The company, maker of Botox, rejected an

unusual hostile bid from

Valeant and a hedge fund. Valeant was

criticized in the

bitter takeover battle

for

cutting R.&D. (2014)

-

SALIX

Faced with the prospect of letting another deal slip through

its fingers, Valeant substantially raised its bid, putting a

quick end to a bidding war. (March 2015)

-

SPROUT

Two days after winning regulatory approval for the first pill

to aid a woman’s sex drive, the company was acquired.

(August 2015)

|

|

Given

that the Securities and Exchange Commission requires companies

reporting pro forma figures to publish GAAP numbers in tandem, you

might assume investors would stay focused on the facts. But academic

research appears to show that adjusted numbers drive stock prices.

Consider a

2002 study on non-GAAP numbers by

Mark T. Bradshaw, an associate

professor of accounting at Boston College, and

Richard G. Sloan, a professor of

accounting at the University of California, Berkeley. The fantasy

numbers had “displaced GAAP earnings as a primary determinant of stock

prices,” its authors wrote.

In an interview,

Mr. Sloan said he was concerned about the proliferation of companies reporting

non-GAAP figures and the challenges that posed to investors.

“I can see the

advantages of letting a company with a good management team do its own voluntary

disclosure to help investors understand over and above what’s in the GAAP

filings,” Mr. Sloan said. “But what goes along with that is companies that use

their own numbers to put them in a better light and to mislead investors.”

Helping

perpetuate these kinds of earnings myths, Mr. Sloan said, are Wall Street

analysts who use companies’ invented figures in reports and stock price

forecasts.

“You’d hope that

Wall Street analysts would recognize you can’t really value a company like

Valeant whose business model is to pay cash to make acquisitions by ignoring the

amount of cash it is using in those acquisitions,” Mr. Sloan said.

Recent Wall

Street research on Valeant highlights this problem. In an Oct. 1 report from

Morgan Stanley, Valeant’s pro forma earnings are identified as “E.P.S.,” leading

many readers to assume a GAAP number. A figure identified in a table as net

income is actually Valeant’s adjusted number, which is far larger than the GAAP

version.

Two recent UBS

reports are also confusing. On Page 1 of both reports, the analyst cited

Valeant’s pro forma figure as “E.P.S.” Later in the report, the analyst

identified the figures as “cash E.P.S.”

At Merrill

Lynch, the Valeant analyst does a better job, presenting both GAAP and pro forma

figures so investors can see the vast differences between the two.

Analysts may

feel compelled to use a company’s adjusted numbers when they reflect standard

industry practice. At the same time, however, going along with a numbers game

may also be a way to stay on good terms with a company’s executives. Analysts

who exert independence can find that managers may refuse to answer their

questions or otherwise turn off the crucial information spigot.

Back in 2003,

after pro forma earnings had begun to gain traction, the S.E.C. wrote a new rule

to try to help investors. Known as

Regulation G, it requires companies using

fantasy figures in regulatory filings to present “with equal or greater

prominence,” comparable financial measures calculated under GAAP. The regulation

does not cover news releases.

Mr. Sloan thinks

it may be time for a new rule. “When they did Reg G, things calmed down for a

little bit,” he said. “Now things are getting out of control again.”

A version of this article appears in print on November 1, 2015, on

page BU1 of the New York edition with the headline: Valeant’s

Fantastic(al) Numbers.

© 2015 The

New York Times Company