Speech

Stock Buybacks and

Corporate Cashouts

Washington D.C.

June 11, 2018

Thank you so much, Neera, for that very kind introduction. I’ve long

admired all that you and everyone here at the Center for American

Progress do to promote a progressive economic agenda. And I share your

commitment to making sure our markets are safe and efficient—and fair

for all Americans. So it’s a real honor to be with you here today.[1]

I also want to thank my friend Andy Green, who in addition to being

Managing Director of Economic Policy here at CAP, has been a critical

source of wisdom for me since my swearing in at the Commission back in

January.

Before I begin, let me start with the standard disclaimer that the

views I’m about to express are my own and do not reflect the views of

the Commission, my fellow Commissioners, or the SEC’s Staff. And let

me add my own standard caveat, which is that I fully expect someday to

convince my colleagues that I am, as usual, completely correct in

everything I say and do.

Today, I’d like to share a few thoughts about corporate stock

buybacks—and some research produced by my staff that raises

significant new questions about this activity. As Neera mentioned, I’m

a recovering researcher. Before I was appointed to the SEC, I was a

law professor who spent most of my time thinking about how to give

corporate managers incentives to create sustainable long-term value.

I’d often ask my students: are we making sure that executive pay gives

managers reason to invest in the long-term development of their

workforce and their communities? Or are we paying executives to pursue

short-term stock-price spikes rather than long-term growth?

Little did I know that, so soon into my tenure, I’d have a sobering

case study to put these questions to the test. That’s because the

Trump tax bill, promising to bring overseas corporate cash home,

became law last December.

Now, we all know what happened the last time a Republican-controlled

government pushed through a corporate tax holiday in 2004. As that

bill’s sponsors hoped, American companies repatriated billions of

dollars of overseas cash.[2]

But corporations didn’t invest most of that money in innovation. They

didn’t invest it in retraining their workforce or raising wages.

Instead, executives largely used the influx of fresh funds for massive

stock buybacks.[3]

So when I first took this job, I worried that 14 years later history

would repeat itself, and the tax bill would cause managers to focus on

financial engineering rather than long-term value creation. Sure

enough, in the first quarter of 2018 alone American corporations

bought back a record $178 billion in stock.[4]

On too many occasions, companies doing buybacks have failed to make

the long-term investments in innovation or their workforce that our

economy so badly needs.[5]

And, because we at the SEC have not reviewed our rules governing stock

buybacks in over a decade, I worry whether these rules can protect

investors, workers, and communities from the torrent of corporate

trading dominating today’s markets.[6]

Even more disturbing, there is clear evidence that a substantial

number of corporate executives today use buybacks as a chance to cash

out the shares of the company they received as executive pay.[7]

We give stock to corporate managers to convince them to create the

kind of long-term value that benefits American companies and the

workers and communities they serve. Instead, what we are seeing is

that executives are using buybacks as a chance to cash out their

compensation at investor expense.

Executives often claim that a buyback is the right long-term strategy

for the company, and they’re not always wrong. But if that’s the case,

they should want to hold the stock over the long run, not cash it out

once a buyback is announced. If corporate managers believe that

buybacks are best for the company, its workers, and its community,

they should put their money where their mouth is. That’s why I’m here

today to call on my colleagues at the Commission to update our rules

to limit executives from using stock buybacks to cash out from

America’s companies.

And I am also calling for an open comment period to reexamine our

rules in this area to make sure they protect employees, investors, and

communities given today’s unprecedented volume of buybacks.

Stock Buybacks and Executive Pay

Basic corporate-finance theory tells us that, when a company announces

a stock buyback, it is announcing to the world that it thinks the

stock is cheap.[8]

That announcement, and the firm’s open-market purchasing activity,

often causes the company’s stock price to jump, so the SEC has adopted

special rules to govern buybacks.

Those rules, first adopted in 1982, provide companies with a safe

harbor[9]

from securities-fraud liability if the pricing and timing of

buyback-related repurchases meet certain conditions.[10]

After experience proved that buybacks could be used to take advantage

of less-informed investors,[11]

the SEC updated its rules in 2003, though researchers noted that

several gaps remained.[12]

In the meantime, the use of stock-based pay at American public

companies has exploded.[13]

Although these pay programs present many challenges, the one that I’ve

spent much of my career thinking about is how to make sure that

corporate management has skin in the game—that is, how to keep top

executives from cashing out stock they receive as compensation.[14]

You see, the theory behind paying executives in stock is to give them

incentives to create long-term, sustainable value.[15]

Because executives who receive shares rather than cash demand higher

levels of pay, the use of stock-based compensation has led to

eye-opening pay packages for top executives. In the trade,

investors—and the economy as a whole—tie executives’ fortunes to the

growth of the company.

But that only works when executives are required to hold the stock

over the long term. Researchers have long worried that executives, who

always prefer cash to stock, will try to sell rather than hold their

shares, eliminating the incentives they were meant to produce.[16]

So it’s no surprise that, in the years leading up to the financial

crisis, top executives at Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers personally

cashed out $2.4 billion in stock before the firms collapsed.[17]

And it’s no wonder that sophisticated investors have for decades

strictly limited executives’ freedom to cash out their shares.[18]

In the wake of the financial crisis, Congress realized the importance

of keeping executives’ skin in the game, so the Dodd-Frank Act

included several provisions designed to give investors more

information about whether and how managers cash out.[19]

Unfortunately, as you all know too well, those rules have still not

yet been completed, keeping investors in the dark about executives’

incentives.

Nearly eight years since that landmark legislation, it is completely

unacceptable that the SEC has still not promulgated these and other

rules required by law. But it’s not just that the regulations haven’t

been finalized. It’s that the problem itself keeps getting worse. You

see, the Trump tax bill has unleashed an unprecedented wave of

buybacks, and I worry that lax SEC rules and corporate oversight are

giving executives yet another chance to cash out at investor expense.

How Executives Use Buybacks to Cash out

That’s why, when I was sworn in a few weeks after the Trump tax bill

took effect, I asked my staff to take a look at how buybacks affect

how much skin executives keep in the game. I was worried that lax

corporate practices and SEC rules might lead to buybacks that give

executives yet another chance to cash out at investor expense.

So we dove into the data, studying 385 buybacks over the last fifteen

months.[20]

We matched those buybacks by hand to information on executive stock

sales available in SEC filings.[21]

First, we found that a buyback announcement leads to a big jump in

stock price: in the 30 days after the announcements we studied, firms

enjoy abnormal returns of more than 2.5%.[22]

That’s unsurprising: when a public company in the United States

announces that it thinks the stock is cheap, investors bid up its

price.

What did surprise us, however, was how commonplace it is for

executives to use buybacks as a chance to cash out. In half of

the buybacks we studied, at least one executive sold shares in the

month following the buyback announcement. In fact, twice as many

companies have insiders selling in the eight days after a buyback

announcement as sell on an ordinary day.[23]

So right after the company tells the market that the stock is cheap,

executives overwhelmingly decide to sell.[24]

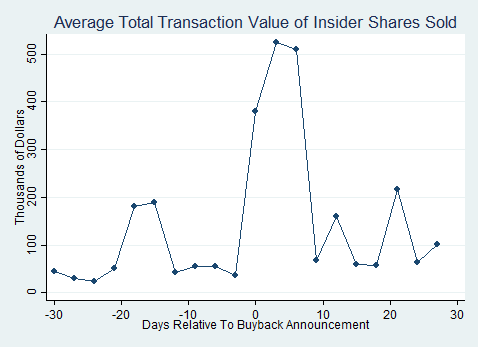

And, in the process, executives take a lot of cash off the table. On

average, in the days before a buyback announcement, executives trade

in relatively small amounts—less than $100,000 worth. But during the

eight days following a buyback announcement, executives on average

sell more than $500,000 worth of stock each day—a fivefold increase.

Thus, executives personally capture the benefit of the short-term

stock-price pop created by the buyback announcement:

Now, let’s be clear: this trading is not necessarily illegal. But it

is troubling, because it is yet another piece of evidence that

executives are spending more time on short-term stock trading than

long-term value creation. It’s one thing for a corporate board and top

executives to decide that a buyback is the right thing to do with the

company’s capital. It’s another for them to use that decision as an

opportunity to pocket some cash at the expense of the shareholders

they have a duty to protect, the workers they employ, or the

communities they serve.

More importantly, policymakers, advocates, investors and corporate

boards have spent decades, and billions of dollars of shareholder

money, trying to tie executive pay to long-term corporate performance.

But the evidence shows that buybacks give executives an opportunity to

take significant cash off the table, breaking the pay-performance

link. SEC rules do nothing to discourage executives from using

buybacks in this way. It’s time for that to change.

The Path Forward

There are two steps we can and should take right away to address the

practice of executives using buybacks as a chance to sell their

shares. First, as I mentioned earlier, the SEC last revised its rules

governing buybacks in 2003. Those rules give companies a so-called

“safe harbor” from liability when pursuing buybacks. But there are no

limits on boards and executives using the buyback—and the safe

harbor—as an opportunity to cash out.

I cannot see why a safe harbor to the securities laws should subsidize

this behavior. Instead, SEC rules should encourage executives to keep

their skin in the game for the long term. That’s why our rules should

be updated, at a minimum, to deny the safe harbor to companies

that choose to allow executives to cash out during a buyback.[25]

And that’s why today I’m also calling for an open comment period to

reexamine our rules in this area to make sure they protect American

companies, employees, and investors given today’s unprecedented volume

of buybacks.[26]

Second, corporate boards and their counsel should pay closer attention

to the implications of a buyback for the link between pay and

performance. In particular, the company’s compensation committee

should be required to carefully review the degree to which the buyback

will be used as a chance for executives to turn long-term performance

incentives into cash. If executives will use the buyback to cash out,

the committee should be required to approve that decision and disclose

to investors the reasons why it is in the company’s long-term

interests. It is hard to see why a company’s buyback announcement

shouldn’t be accompanied by this kind of disclosure.[27]

Executives who can’t sell their holdings in the short term—but instead

have to create real value over time—have far fewer incentives to

manage to quarterly earnings and pursue the kind of short-term

thinking that dominates our economy today. The esteemed experts on our

next panel will, I’m sure, offer broader policy proposals that can

help us address those problems. But at the SEC, it’s time for our

rules to require corporate managers who say they want to manage for

the long term to put their money where their mouth is. At the very

least, our rules should stop giving executives incentives to use

buybacks to cash out.

* * * *

The increasingly rapid cycling of capital at American public companies

has had real costs for American workers and families. We need our

corporations to create the kind of long-term, sustainable value that

leads to the stable jobs American families count on to build their

futures. Corporate boards and executives should be working on those

investments, not cashing in on short-term financial engineering.

Each day when I arrive at work, I’m reminded that the SEC’s mission is

to protect investors, ensure a level playing field in our financial

markets, and encourage capital formation. Updating our rules to

reflect the effects of buybacks on executives’ incentives to create

long-term value would serve all three of those goals.

Investors deserve to know when corporate insiders who are claiming to

be creating value with a buyback are, in fact, cashing in.[28]

A level playing field requires that shareholders selling into a

buyback know what managers are doing with their own money. And

investors who feel assured that buybacks won’t be used as a chance for

insiders to cash in will be more willing to fund the kinds of

long-term investments our economy needs.

All of you here at CAP have provided essential leadership in

developing policies that produce growth for all Americans—and favor

long-term value creation over financial engineering. That’s why I’m so

proud to be here today. I’m very much looking forward to your

questions. And I so look forward to working with you to ensure that

the SEC’s policies create the kinds of markets that American families

need—and deserve.

[1] Commissioner,

United States Securities and Exchange Commission. I am, as always,

grateful to my SEC colleagues Bobby Bishop, Caroline Crenshaw, Marc

Francis, Satyam Khanna, Prashant Yerramalli, and Jon Zytnick for their

invaluable counsel. Professor Jesse Fried of the Harvard Law School

also provided insights that significantly deepened my thinking about

these matters. The views expressed here are solely my own, and do not

necessarily reflect those of the Staff or my colleagues on the

Commission, though I hope someday they will.

[2] See

American Jobs Creation Act, Pub. L. No. 108-357, 118 Stat.

1418-1660 (2004).

[3]

Although the degree to which corporations used the proceeds of

the 2004 holiday for buybacks is debatable, whether they did

so—even though the statute prohibited such uses—is not. Compare

Dhammika Dharmapala, C. Fritz Foley, and Kristin J. Forbes, Watch

What I Do, Not What I Say: The Unintended Consequences of the Homeland

Investment Act, 66 J. Fin. 753 (2011) with Thomas J.

Brennan, Where the Money Really Went: A New Understanding of the

AJCA Tax Holiday (Northwestern Law and Economics Working Paper)

(2014). What’s worse, “the temporary holiday conditioned firms to

anticipate future holidays and to change their behavior by placing

more earnings overseas than ever before.” Thomas J. Brennan, What

Happens After a Holiday? Long-Term Effects of the Repatriation

Provisions of the AJCA, 5 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol’y 1 (2010).

[4]

Talib Visram, Tax Cut Fuels Record $200 Billion Stock Buyback

Bonanza, CNN.com (June 5, 2018); see also William Lazonick,

Stock Buybacks: From Retain-and-Reinvest to Downsize-and-Distribute,

Brookings Initiative on 21st Century Capitalism (April 2015), at 2

(“Over the decade 2004-2013, 454 companies in the S&P 500 Index in

March 2014 that were publicly listed over the ten years did $3.4

trillion in stock buybacks, representing 51 percent of net income.”).

[5]

Savvy market observers also worry that the magnitude of this year’s

buyback spree reflects a troubling trend in corporate investment.

See, e.g., Matt Egan, Goldman Sachs Warns Against Falling in

Love with Stock Buybacks, CNNMoney.com (April 26, 2018) (noting a

recent equity research report describing the perhaps-unsurprising

result that, since the 2016 presidential election, “Goldman Sachs’s

collection of stocks that are focused on capital spending and research

and development soared 42% . . . besting the S&P 500’s 24% gain”).

[6]

For an exceptionally clear demonstration as to how buybacks can harm

investors while benefiting insiders, see Jesse M. Fried, Insider

Trading Via the Corporation, 162 U. Pa. L. Rev. 801, 805 (2014)

(referring to stock buybacks as “indirect insider trading” and noting

that such “trading likely imposes considerable costs on public

investors in two ways. First, just like ‘ordinary’ direct insider

trading, indirect insider trading secretly redistributes value from

public investors to insiders. . . . Second, the use of the corporation

as a vehicle for insider trading can lead insiders to waste economic

resources.”).

[7]

In these remarks, I focus on executives’ use of buybacks to cash out

shares granted as part of compensation packages otherwise designed to

link executive pay with long-term performance. There are, of course,

circumstances where managers who founded the firm or are otherwise

large shareholders seek liquidity for those holdings using buybacks.

Those cases, too, should be addressed if the SEC chooses to reevaluate

its rules in this area. But here I focus on cases where executives use

buybacks to cash out shares granted as stock-based pay.

[8]

See, e.g., George Constantinides & Bruce Grundy, Optimal

Investment with Stock Repurchase and Financing as Signals, 2 Rev.

Fin. Stud. 445 (1989) (providing a theoretical model on the role of

repurchases when a firm is undervalued).

[9]

Among other reasons, a safe harbor is necessary because firms often

pursue buybacks under informational circumstances that might lead to

securities-law liability in other contexts. See Fried, supra

note 5, at 813-814 (“The SEC takes the position that Rule 10b-5 .

. . applies to a firm buying its own shares.”).

[10]

Securities and Exchange Commission, Final Rule: Purchases of Certain

Equity Securities by the Issuer and Others, Release Nos. 33-8335,

34-48766, 17 C.F.R. Pt. 228 et seq.

[11]

For example, because these rules permitted firms to announce a

buyback—generating a stock-price spike—and then choose not to buy back

any stock at all without disclosing that fact to investors,

commentators and the SEC worried that managers opportunistically used

buyback announcements to manipulate share prices. See, e.g.,

Jesse Fried, Informed Trading and False Signaling with Open Market

Repurchases, 93 Cal. L. Rev. 1323, 1336-40 (2005); see also

Final Rule, supra note 8 (“Studies have . . . shown that some

issuers publicly announce repurchase programs, but do not purchase any

shares or purchase only a small portion of the publicly disclosed

amount.”).

[12]

See Final Rule, supra note 8. Among other things,

commentators have pointed out that the SEC’s still-lax disclosure

rules regarding buybacks give corporate insiders “a strong incentive

to exploit [those] rules in order to engage in indirect insider

trading: having the firm buy and sell its own shares at favorable

prices to increase the value of the insiders’ equity.” Fried, supra

note 8, at 804. Indeed, there is important evidence that the

limited tightening of disclosure rules in this area have had some

benefits in addressing opportunistic buyback activity. See

Michael Simkovic, The Effect of Mandatory Disclosure on Open-Market

Stock Repurchases, 6 Berkeley Bus. L. J. 98 (2009). That evidence

makes the case for revisiting these rules now all the more compelling.

Indeed, the Commission issued a proposal to update these rules in

2010, see Proposed Rule, Purchases of Certain Equity Securities

by the Issuer and Others, Release No. 34-61414 (2010), but to date has

taken no action on the proposal.

[13]

See, e.g., Kevin J. Murphy, Executive Compensation: Where We

Are and How We Got There, in George Constantinides, Milton

Harris, and Rene Stulz, Eds., Handbook on Economics and Finance 211

(2013).

[14]

See, e.g., Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Stock Unloading and

Banker Incentives, 112 Colum. L. Rev. 951 (2012); Robert J.

Jackson, Jr. & Colleen Honigsberg, The Hidden Nature of Executive

Retirement Pay, 100 Va. L. Rev. 479 (2014); Robert J. Jackson, Jr.

& Jonathon Zytnick, The Effects of a Tax Notch on CEO Golden

Parachute Contracts and Option Exercises (working paper 2018).

[15]

See, e.g., Kevin Murphy, Executive Compensation, in

Orley C. Ashenfelter & David Card, Eds., 3B Handbook of Labor

Economics 2485 (1999).

[16]

See Lucian A. Bebchuk, Jesse Fried, and David Walker,

Managerial Power and Rent Extraction in the Design of Executive

Compensation, 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 751 (2002); see also

Lucian A. Bebchuk & Jesse Fried, Paying for Long-Term Performance,

158 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1915, 1921 (2010) (describing concerns related to

“ensuring that, whatever equity incentives are used [in executive pay,

executives’] payoffs are primarily based on long-term stock values

rather than on short-term gains that may be reversed.”).

[17]

Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Holger Spamann, The Wages of

Failure: Executive Compensation at Bear Stearns and Lehman 2000-2008,

27 Yale. J. Reg. 257 (2012).

[18]

Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Private Equity and Executive Compensation,

60 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 638, 640 (2013) (“[T]he pay-performance link is

much weaker in public companies than in companies owned by private

equity investors. Borrowing from their private equity counterparts,

public company boards seeking to strengthen the link between pay and

performance should restrict CEOs’ freedom to unload.”).

[19]

See, e.g., Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act §§ 953(a), 954, 955, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat.

1376 (2010) (requiring the SEC to adopt rules requiring disclosure of

the pay-performance link, public companies’ policies related to the

clawback of erroneously awarded compensation, and policies related to

insider hedging of public companies’ stocks, none of which has been

finalized).

[20]

We drew information on buybacks from the Securities Data Company (SDC)

database, using transactions identified by SDC as buybacks with

announcements in the year 2017 and the first three months of 2018. For

consistency in treatment across the sample, we identify an initial

sample of 708 repurchases and retain only the first repurchase

announcement by each company—and only those repurchases not followed

by a subsequent repurchase announcement within 60 days. We merged

those data with information from the Center for Research on Securities

Prices (CRSP) database, leaving a sample of 385 public company

buybacks.

[21]

We used data from Form 4 filed pursuant to Section 16. See

Securities and Exchange Commission, Ownership Reports and Trading By

Officers, Directors and Principal Securities Holders, 56 Fed. Reg.

7,242 (Feb. 21, 1991); see also Securities and Exchange

Commission, Mandated Electronic Filing and Web Site Posting for Forms

3, 4 and 5, 68 Fed. Reg. 25,788 (May 13, 2003).

[22]

That finding is consistent with the longstanding finance literature on

the effects of these announcements on stock prices. See, e.g.,

David Ikenberry, Josef Lakonishok, and Theo Vermalen, Market

Underreaction to Open Market Share Repurchases, 39 J. Fin. Econ.

181 (1995); Jesse M. Fried, Insider Signaling and Insider Trading

with Repurchase Tender Offers, 67 U. Chi. L. Rev. 421 (2000).

[23]

On an average day, between 3 and 4 percent of corporate insiders trade

in the company’s stock, but we found that, during the eight days

following a buyback announcement, more than 8 percent do. We direct

the interested reader to the data appendix to this speech, where you

can learn more about our methodology and analysis.

[24]

Investors receive a mixed signal from a buyback announcement that is

accompanied by insider selling. Indeed, as we explain in our data

appendix, we observe statistically significantly lower returns during

the ten- and thirty-day window following buyback announcements with

executive selling than we do in buybacks where executives hold their

shares for the long term.

[25]

The precise way in which the safe-harbor could be restructured to

disfavor the use of buybacks for insider sales is beyond the scope of

my remarks—and, in all events, well within the expertise of our

exceptional Staff. Suffice it to say that, if the Commission were so

inclined, our Staff would have little difficulty making sure that our

rules are not used in a way that encourages corporate executives to

use buybacks to sell their shares.

[26]

We should also use this opportunity to review other problems with Rule

10b-18 and related rules—including the fact that they require only

quarterly disclosure of the amount of shares a company has actually

repurchased, leaving investors largely in the dark about corporate

trading in their own shares. For an exceptionally thoughtful proposal

in this respect, see Fried, supra note 5.

[27]

Except, of course, the fact that our rules let them. See Final

Rule, supra note 8; but see Schnell v. Chris-Craft

Industries, Inc., 285 A.2d 437, 444 & n.15 (Del. 1971) (“Inequitable

action does not become permissible simply because it is legally

possible.”).

[28]

It’s true, of course, that investors eventually receive

disclosure of executives’ selling on Form 4, which is how we were able

to conduct this study. But those disclosures come after the

executive has already sold—too late for shareholders to price the

executive’s decision into their own determination whether to sell

their shares. See Fried, supra note 5. |