|

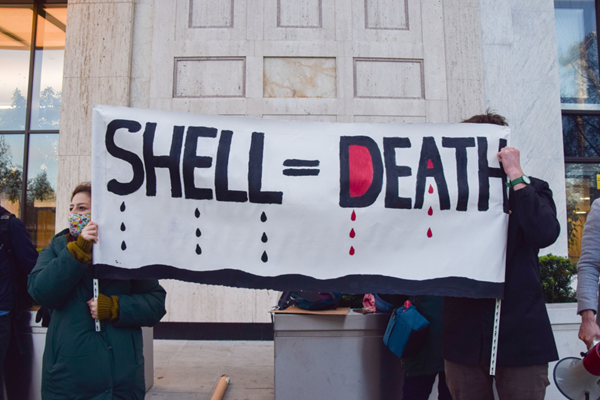

Fintech startups offer a new way for

shareholders to express themselves.

Photographer: SOPA Images/LightRocket |

By

Matthew Brooker

November 23, 2022 at 12:00 AM EST

The global

pandemic’s wrenching disruptions have had an array of unforeseen

economic and social consequences, from gluts of office

space to developmental challenges for children.

Not many forecasters are likely to have had “revived shareholder

democracy” on their bingo cards. Bravo to anyone who did.

The part that

lockdown boredom played in inspiring the meme-stock

craze is acknowledged. Less appreciated may be its role in

a shift to greater exercise of investor voting rights. UK startups

Tulipshare Ltd. and Tumelo are at the forefront of a movement to

bridge the gap between ultimate shareholders and the companies they

collectively own. This may not generate quite the same viral buzz as

the GameStop Corp. frenzy, but it’s a trend with potentially

longer-lasting and more profound effects on the investing landscape.

Think of it as

the serious elder sibling of the meme-stock mania. If the typical

GameStop or AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. buyer was a millennial

lying on the sofa laughing about the fun of messing with hedge fund

short sellers, then the typical Tulipshare customer might be pictured

as a millennial lying on the sofa worrying about how the world will

survive.

The Tulipshare platform lets

individual investors pool their stakes so they can meet the threshold

for submitting shareholder proposals and put pressure on companies to

adopt more socially responsible behavior. In effect, it allows any

shareholder, however small, to become an activist. The company,

founded in July 2021, posted a 166% increase in users to 27,000 for

the third quarter. Founder Antoine Argouges said in an interview he

aims to have close to 1 million “from Berlin to Los Angeles” in 2025.

The rise of such

platforms hasn’t exactly flown under the radar, with Tulipshare taking

on some of the biggest companies in the world in its short existence.

Its campaigns have included pressing Coca-Cola Co. to use fewer

plastic bottles and urging Johnson & Johnson to end talc sales (a step

the health-care company took

in August). Most notably, it drew support from 44% of

Amazon.com Inc. shareholders for an unsuccessful

resolution in May calling for an

investigation of working conditions at its warehouses. “This is the

stuff of a financial revolution,” Argouges said.

Four-year-old Tumelo,

meanwhile, is more focused on institutions such as pension providers

and asset managers, providing tools that enable more than two dozen

including Legal & General Investment Management Ltd. and Fidelity

International Ltd. to identify and channel the voting wishes of

beneficial owners. “The momentum is really increasing,” CEO and

co-founder Georgia Stewart told me, saying she expects the company is

on the cusp of “exponential growth.”

The question now

is whether these changes are permanent or fads that will disappear as

Covid recedes. Meme stocks have fizzled (while showing periodic signs

of life) and pandemic-fueled enthusiasm for crypto has

taken a beating from the collapse of FTX, but the trend toward

shareholder enfranchisement looks less likely to reverse.

Even before

Covid left millions with excess time to spend on their brokerage apps,

a confluence of factors was pointing toward greater shareholder

engagement, among them: the increasing attention given to

environmental, social and governance issues; the expanding

capabilities of fintech, and political polarization in the US — but

probably nothing as influential as the rising power of passive

investing.

Low-cost index

funds have increasingly come to dominate the asset management

industry: BlackRock Inc., the world’s biggest money manager, had

almost $8 trillion of assets under management as of the end of

September. But this has left a democratic though — BlackRock’s Chief

Executive Officer Larry Fink sees a new era of “shareholder

democracy” coming and pledged to extend voting power to

more of the firm’s clients. How should the providers of index funds,

with their market heft, vote their holdings? The active manager, who

has chosen to buy stock X or Y, can be expected to have a view on

corporate policies and vote accordingly in the interests of the

ultimate owners. The passive manager, by definition, has no such

opinion — he or she just buys every stock in proportion to its

weighting in the index.

This conundrum

arrives just as investors become more interested in knowing that the

companies in which their money is invested are doing the right thing.

That’s easier said than done. Millions of us contribute to pensions

while having little idea of where precisely the funds go or how the

investment manager would vote on issues we might care about — like

net-zero targets or labor conditions. Imagine if you could log on to

your pension provider, see upcoming shareholder decisions and click to

indicate how you would like your vote to be used? That’s what Tumelo

and its competitors provide.

Skeptics

question how great the impact of returning votes to owners will be,

and argue it may be the opposite of what advocates expect. For one

thing, most US shareholder proposals are non-binding: Company boards

can ignore them if they choose. What’s more, it will have the effect

of dispersing votes. At present, a fund manager can vote an entire

block of shares, and can potentially use that leverage to influence

management. Once the company knows that the fund no longer controls

those votes, it has less incentive to listen.

That’s no reason

for not doing it. As a matter of principle, the votes belong to the

owners. The separation of ownership and control, a function of the

complexity of modern capitalism, has long been recognized as a

corporate governance challenge. Restoring that link may have results

that are as yet impossible to predict, but they are likely to be

mostly positive: driving new levels of engagement, encouraging people

to care about a process from which they have become alienated, and

potentially even reviving

faith in the economic system. This trend is to be welcomed.