Score one for

shareholders.

It doesn't look like

Michael Dell, founder, chairman, and CEO of

Dell, will be able to steal his company from public

shareholders for just $13.65 a share now that superior preliminary

offers for Dell have been submitted by Blackstone Group and activist

investor Carl Icahn.

It's harder than it

once was to buy businesses at unfairly low prices because

deep-pocketed investors like Icahn are prowling the markets for

opportunities. Moreover, big institutional holders are no longer

pushovers. The Dell buyout, first announced in early February,

probably was doomed due to widespread opposition from the company's

larger shareholders, including Southeastern Asset Management, with

7% of the shares, and T. Rowe Price.

|

![[image]](http://barrons.wsj.net/public/resources/images/BA-BB470_TOC_i_DV_20130330001418.jpg) Scott Pollack for Barron's

Scott Pollack for Barron's

|

|

Blackstone, led by CEO

Stephen Schwarzman, and Icahn admittedly aren't willing to pay much

more than the buyout price offered by Michael Dell and his sidekick,

Silver Lake Partners. But they will allow at least some Dell

shareholders to remain as investors in a publicly traded Dell. Under

the $24 billion deal initiated by Michael Dell, all investors would

be forced to sell.

Yet many Dell holders

believe the company, which sells personal computers, software, and

technology services, is worth more than $20 a share, based on its

earnings power, and want to participate in its potential revival.

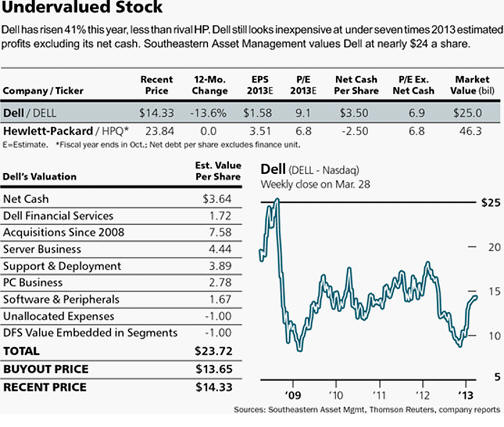

Southeastern pegs Dell's value at almost $24 a share, based on

acquisitions that diversified the company's operations. Dell rose 19

cents, to $14.33, last week.

Blackstone has proposed

paying "in excess" of $14.25 a share for Dell -- it won't specify

how much more -- while Icahn is offering $15 for as much as 58% of

the Round Rock, Texas–based company.

Both proposals, which

came at the end of a 45-day "go shop" period for alternative offers,

amount to what Wall Street calls a leveraged recapitalization,

meaning a large chunk of stock would be retired. Investors who stick

around will be left with shares in a more debt-laden company that

offers both greater upside potential and downside risk than before.

Dell's share count, now nearly 1.8 billion, could fall to one

billion or less. Debt will rise with the recap, but likely not to

onerous levels.

|

Antoine Antoniol/Bloomberg

News; Tony Avelar/Bloomberg News; Edward Le Poulin/Corbis

Leading actors in

the Dell drama, from left: Blackstone Group's Stephen

Schwarzman, Dell CEO Michael Dell, and activist investor Carl

Icahn. |

|

OUR BET IS THAT

THE FINAL DEAL will give investors a chance to cash out at

$15 a share or more. Those who remain invested ultimately could wind

up with considerably more than $15, based on an analysis from

Southeastern and others. The stock surely looks inexpensive at just

nine times this fiscal year's projected profit of $1.57 a share, and

seven times estimated earnings after excluding the company's net

cash position (cash and marketable securities, less debt) of $6.3

billion, or $3.50 a share.

"Having the choice of

cashing out or staying in is hugely superior to what Michael Dell

had to offer," says Richard Pzena, co-chief investment officer at

Pzena Investment Management, which owns about 1% of the company.

"It's inconceivable that the Dell board can come to another

conclusion."

Barron's has

written critically -- and presciently -- about the Dell buyout bids

since before Michael Dell's was announced on Feb. 5. In a Jan. 21

story, "How

to Give Dell's Shareholders a Fair Deal," we wrote that a

then-rumored deal price of $14 a share significantly undervalued the

company and would run into shareholder opposition. We also

speculated that Dell could attract an activist investor like Icahn,

and argued that a better alternative to a buyout would be a tender

offer for Dell shares at $15 a share.

These events have since

occurred, even though most Wall Street analysts and media

commentators initially treated the Michael Dell deal as a near

certainty.

The coming battle may

be over investor participation in a publicly traded Dell, an issue

that has received little attention to date, amid coverage of the

Blackstone and Icahn bids. Any deal approved by Dell's board is

likely to enable at least some current shareholders to remain

invested.

Barron's

analysis suggests that half of Dell's holders would like to stay

invested in the company, which Michael Dell, 48, founded in 1984.

Icahn believes it is fair to offer them this opportunity, as his

proposal gives shareholders the option of staying in or cashing out.

Blackstone's

preliminary proposal is murkier on this score. Blackstone says it

plans to "cap" the number of investors that would be allowed to

remain as shareholders.

It isn't clear what

Michael Dell might offer in a counter proposal.

Under one scenario,

Blackstone potentially could form a "club" deal with Michael Dell,

Icahn, and perhaps another big holder, and then try to force out

most investors at about $15 a share. That likely would generate

strong investor objections, however, as well as lawsuits.

Let's do the

shareholder math: Michael Dell owns 16% of the company and is

unlikely to sell any shares at about $15, whether he's involved in

the winning group or not. Icahn, a 4% owner, won't sell at $15 and

wants to buy more stock at that price. Southeastern and T. Rowe

Price, a 4% holder, believe Dell is undervalued and probably won't

sell at $15. These four holders together own more than 30% of Dell,

and there are many smaller institutional holders, including Pzena,

and retail investors, who presumably want to stay invested.

WHY WOULD SO

MANY DELL HOLDERS want to stick with a company that has

little support from Wall Street and is widely derided as a has-been

by the media?

Dell's diversification

is reflected in Southeastern's analysis. The firm assigns a value of

just $2.78 a share to the PC business (see table), but assumes that

the Dell acquisitions are worth the price paid by the company. One

successful deal was for Quest Software, a $2.5 billion purchase last

year that probably is worth more than what Dell paid. Add Dell's

cash, server business, and financial arm, and the total value

approaches $24 a share.

Icahn values Dell at

more than $22 a share. Retiring a large chunk of Dell's shares would

boost the company's earnings per share, since likely debt costs of

about 6% are below the earnings yield of about 11%. (The earnings

yield is the inverse of the price/earnings ratio.)

This is evidently what

Michael Dell and Silver Lake see. Dell, who is worth an estimated

$15 billion, was a big seller of the company's shares a decade ago

when the stock traded above $30, and now senses opportunity. So does

Silicon Valley–based Silver Lake, a shrewd bottom-fisher in tech.

The private-equity firm led a group that bought 70% of Skype from

eBay (EBAY) for $1.9 billion in 2009, and then flipped it

to

Microsoft (MSFT) for $8.5 billion in 2011. As Ben Stein

wrote in Barron's, the Dell buyout proposal smacked of

insider trading because Michael Dell, who probably knows more about

the company than anyone, should be required to put shareholder

interests ahead of his own ("Dell

Deal: The Same as Insider Trading," Feb. 18).

That was echoed last

week by investment manager Leon Cooperman of Omega Advisors, who

told the New York Times, "Dell has a moral responsibility to work

for his shareholders."

Referring to the

buyout, Cooperman added: "He's not doing this because he thinks his

company is overvalued. He wants to make money."

THE FOUR-MEMBER

SPECIAL COMMITTEE of the Dell board that approved the

Michael Dell buyout deal apparently wasn't troubled by Dell's role.

That committee looked to be so concerned by Dell's weakening profits

that it OK'd the low-ball price. The committee defends itself,

stating that it "conducted a disciplined and independent process

intended to ensure the best outcome for shareholders."

The committee should

have done better, particularly since one of its members is Laura

Conigliaro, a former Goldman Sachs technology research analyst who

covered Dell as recently as 2007. As Barron's has reported,

Conigliaro had a $35 price target on Dell in October 2007, according

to a story posted at the time on MarketWatch.com, which also is

owned by Barron's parent Dow Jones. That target was in

place before she gave up her analyst responsibilities to become

co-head of Goldman's Americas research group. She retired from

Goldman as a partner in 2011.

Dell was much more

highly regarded in 2007 than now, but Conigliaro carried that $35

price target when the stock traded at $30 and the company had about

$1.30 of annual earnings power. She voted in favor of a deal at

$13.65, with Dell's profits having risen to $1.72 a share in 2012.

THE BUYOUT

PROXY, released late Friday, details the negotiations over

many months that led to the February deal and the eroding internal

financial projections that motivated the special committee to

embrace the Michael Dell offer. Because those internal projections

had been leaked prior to Friday in an effort to defend the buyout,

the numbers come as no surprise and probably will do little to sway

investors who oppose the deal.

Projections for

operating income in the fiscal year ending next January have come

down sharply since July, when the company was expected to report

$5.6 billion for the current fiscal year. The subsequently lowered

outlook is already reflected in current Wall Street estimates and

was known to the Dell board in January.

A revised March

management projection of $3.7 billion for the current year looks

consistent with the Street estimate of $1.58 a share in earnings. An

alternative and more conservative March projection, prompted by a

board request, is $3 billion. Dell maintains two internal

projections. The $3 billion is the leaked number that supposedly

underscores Dell's grim outlook, but it seems more of a worst-case

scenario than a likely outcome.

Even if Dell's

operating profit is only $3 billion in fiscal 2014, the company

still could earn about $1.30 a share for the year. That means the

special committee approved a buyout at 10 times a pessimistic 2014

forecast, or less than eight times earnings, excluding net cash. No

major company has ever gone private at such a low valuation.

THE DELL DRAMA,

which began last August with a discussion between Michael Dell and

Silver Lake, could go on for months because Blackstone and Icahn

need to firm up their bids with committed financing. Michael Dell

and Silver Lake would then get a chance to top any proposal deemed

superior by the special committee; Blackstone or Icahn would get

final topping rights.

Dell thus could waste a

year on a buyout ordeal that has distracted management from its

business challenges.

It is possible and

perhaps fitting that Michael Dell could lose his job under the terms

of the final deal. There have been leaked reports that he has talked

to Blackstone, which supposedly is amenable to his participation in

its buyout bid. But Blackstone, like most private-equity firms,

wants some control over businesses it buys, and might not want a

headstrong founder around to second-guess the firm.

Should Michael Dell

drop his bid and align with Blackstone, that would trigger a nice

payday for Silver Lake, which stands to pocket a $180 million

break-up fee.

The Michael Dell camp

has argued that absent a buyout, Dell stock would plunge. But that's

unlikely. Shares of rival

Hewlett-Packard (HPQ) are up 67%, to $24, this year, as

investors smell the early signs of a recovery. Dell shares are up

just 41% in the same period.

Dell's board made a

mistake in approving the Michael Dell buyout. It now has a chance to

redeem itself.