Investors who think that

the price is inadequate have surely been disappointed that a higher bid

never emerged. One big Dell investor, Southeastern Asset Management,

has estimated that the company is worth almost $24 a share.

But many shareholders may

not realize that they have an intriguing alternative that could generate

more money than Mr. Dell is offering: requesting that a court appraise

the company’s long-term value.

Because Dell is

incorporated in Delaware, such an appraisal process would go through

that state’s Court of Chancery. Upon the case’s conclusion,

Delaware law would require Mr. Dell to pay the shareholders bringing

the litigation whatever value the court determined was fair.

Going the appraisal route

has its risks. One big one is that the court could award shareholders

less than the $13.65 a share that Mr. Dell is offering. The cases also

take time, during which investors’ stock is tied up.

But in the Dell case, an

innovative trust has been set up by an outside group allowing Dell

shareholders to pursue appraisal-rights litigation while also allowing

them to sell their shares. More on that later.

Shareholders making legal

challenges to buyouts typically base them on a supposed breach of duty

by company directors overseeing the process. No such breach is required

in appraisal litigation. Investors simply agree to disagree on the

proposed purchase price and ask a court to assess the company’s value.

Nevertheless, because of procedural complexities, appraisal litigation

in takeovers is not that common.

Often purchasers limit

shareholder participation in appraisals to minimize their financial

exposure should a judge rule that a higher price is in order. But Mr.

Dell’s offer did not limit how many shareholders could mount an

appraisal case.

In the Dell transaction,

said

Lawrence A. Hamermesh, a professor of corporate and business law at

Widener Law School in Wilmington, Del., appraisal litigation could be “a

safety valve on doubts about whether a valuation process worked

appropriately.”

“No matter how effective

you think special committees are, some people genuinely believe the

result isn’t fair,” he said. “So this is a way of giving people access

to a court to make that determination.”

For appraisal litigation to

proceed in the Dell case, a majority of the company’s shareholders — not

counting Mr. Dell — must first approve his offer. Only then can

investors who chose not to tender their shares bring an appraisal case.

“What makes this an

interesting case for appraisal is you rarely see going-private deals of

this size,” said

Jeffrey Gordon, a professor at Columbia Law School. “If you’re a 3

percent or 5 percent owner, the litigation cost of an appraisal case for

Dell is a tiny fraction of the potential upside.”

The outcomes in past

appraisal cases suggest that such litigation can pay off handsomely.

Some 40 appraisal cases from 1984 through 2004 that culminated in court

decisions were cited in an unpublished paper by Charles Korsmo,

assistant professor at the Case Western Reserve School of Law, and Minor

Myers, associate professor at Brooklyn Law School.

The professors found that

in the 40 cases where both the merger premium and the court’s finding

were disclosed, appraisal litigation generated a median award of 50.2

percent over the buyout price. Mr. Myers noted in an interview, however,

that some of the cases involved small, private companies where a large

premium did not amount to all that much in dollars.

Eric M. Andersen, a lawyer

specializing in appraisal litigation at the law firm of Mark Andersen in

Wilmington, Del., has also studied cases that went to trial. His

analysis identified 46 since 1985; among those, the court assigned a

lower price in only seven of them. The median premium paid in cases

analyzed by Mr. Andersen was approximately 72 percent.

Another benefit to joining

an appraisal case, lawyers say, is that Delaware law gives participating

shareholders 60 days after a shareholder vote to change their minds and

tender their shares. So why haven’t there been more appraisal cases in

recent years? Operational hurdles and costs have made it hard for both

institutional and individual investors to participate in such

litigation.

But some of the main

hurdles are being eliminated in the Dell case

by the Shareholder Forum, an independent creator of programs devised

to provide the kind of information investors need to make astute

decisions.

The forum, overseen by Gary

Lutin, a former investment banker at Lutin & Company, has created a

trust registered in Delaware to which shareholders seeking to exercise

their appraisal rights can assign their stock and pursue the case as a

group. The Dell Valuation Trust, as it is known, will oversee the

process, hiring lawyers to represent the shareholders in Chancery Court.

This will allow individual investors, who would find it too onerous to

hire their own lawyers, to demand appraisal rights as well.

The trust will also provide

another benefit to investors: freedom to trade their rights. Ordinarily,

shares of investors seeking appraisal rights in a deal are frozen until

the court comes to a decision, which can take as long as two years. But

the securities held in the Dell trust will continue to trade as the case

proceeds.

Shares deposited by

investors into the Dell Valuation Trust will be exchanged, one to one,

for a security representing the appraisal rights. Investors will be able

to buy and sell these instruments throughout the legal process with

their price reflecting the market’s view of a potential outcome. As

such, investors, like mutual funds, who can’t or don’t want to hold

illiquid securities will be able to participate in the appraisal

litigation. The Shareholder Forum charges one penny per share

represented.

“Most investors had viewed

appraisal rights as a perfect theoretical solution for underpriced

buyouts, but impractical because of administrative burdens and lack of

marketability,” Mr. Lutin said. “The analytical view of professional

investors is fairly consistent — assuming appraisal rights are

marketable, processing a demand essentially reserves a no-risk option.”

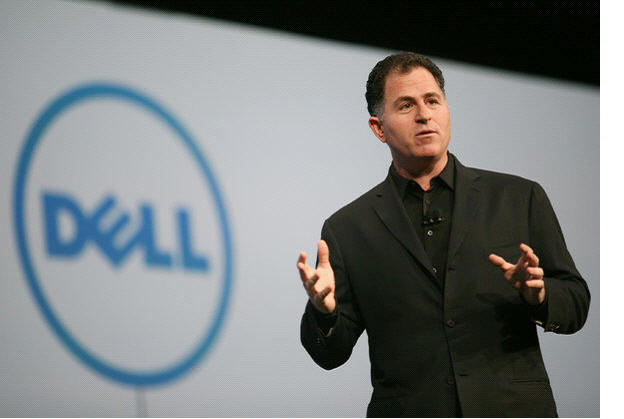

“Most investors look

at this the same way Michael Dell does, and reach the same conclusion,”

Mr. Lutin added. “They want the long term value of the company, not the

short term value of the stock price."

Mr. Dell’s deal might be

approved, or it might not. But providing a low-cost tool for investors

to exercise appraisal rights means that they may occur more often. And

that’s a good thing.