|

|

Chairman and chief executive Michael Dell |

©Bloomberg |

|

In

New York, mergers and acquisitions are the province of investment

bankers with slicked-back hair and polished wingtips. But, if a deal

price does not meet with universal cheers, the battlefield often

shifts from a Manhattan conference room to a Delaware courtroom

because US companies are domiciled in that state. There, the focus

suddenly shifts to egghead professors sporting pocket protectors who

offer competing, and often different, calculations of how much a

company is worth.

In

one closely watched case

decided two weeks ago, the

focus was on the technology company, Dell, which was taken private by

founder Michael Dell in 2013. Some investors believed they had been

short-changed, so they challenged the price in what has become known

as an “appraisal” case.

Once an

obscure quirk of Delaware law, appraisal has become a key remedy for

shareholders and a tool for opportunistic hedge funds. When a company is

sold for cash, unhappy stockholders can exercise so-called “dissenters”

rights and ask a judge to assign a new value for their shares. This

court-determined price can be higher than the deal price or lower. But, in

many cases, it turns out to be the same because judges opt to defer to the

deal.

It can be

reached in a less rounded way, however.

When

bankers advise company boards about what would constitute an acceptable

buyout price, they often present a series of different calculations on a

grid. A premiums analysis shows how much recent deals exceeded market

trading prices. A “capitalised” earnings calculation applies a

multiplication factor to an earnings forecast. Another approach involves

adding up future cash flows and discounting them to reach a fair value

today. For bankers, valuation is the painting of an intricate mosaic.

Alas, the

Delaware court is often less nuanced. Although the appraisal statute has

been interpreted to allow judges to choose whatever valuation method(s) they

deem appropriate, in virtually all recent cases — including Dell — the court

has relied solely on discounted cash flow. “The DCF valuation methodology

has featured prominently [because it] merits the greatest confidence within

the financial community,” the court has said. DCF also happens to be the

favoured approach of scholars because of its theoretical elegance: an

asset’s value should strictly be equal to the net cash it generates.

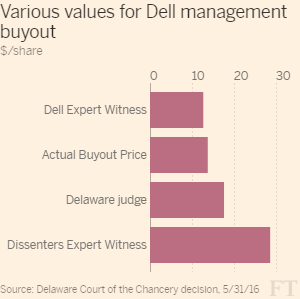

In the Dell

dispute, the company’s expert witness was noted Columbia Business School

economist Glenn Hubbard, best known for advising Republican politicians.

Dell’s shareholders, seeking a higher price, retained Bradford Cornell of

Caltech, the university that is home to Nasa’s rocket laboratory. They are

among around a dozen valuation experts who can bill $1,000 per hour for

their services, and work as affiliates of litigation consultancies — the

best known being Analysis Group, Charles River Associates, Compass Lexecon

and NERA. They are not formal employees but get to use the firms’ resources

— notably an army of spreadsheet jockeys to do the supporting maths.

Despite the

Delaware court’s confidence in DCF, the Dell expert’s use of it proved

contentious. Dr Hubbard’s DCF, for the Dell side, computed that the company

was worth $12.68 per share, suggesting that the $13.75 per share buyout

price was a magnificent win for shareholders. Mr. Cornell, for the

dissenters, concluded Dell was worth a wild $28.61 per share. As the judge

wryly noted, this implied a $28bn aggregate valuation difference on a buyout

worth only $25bn. Still, the judge thought the differences on their inputs

to the calculations — profits, debt and equity levels, discount rates, cash

adjustments — were all arrived at in good faith. So he cherry-picked the

bits of each professor’s work that he found most defensible, to reach a

valuation of $17.62 per share.

It seems

the court is aware of the peril in this approach, writing in an earlier

case: “The value of a corporation is not a point on a line, but a range of

reasonable values, and the judge’s task is to assign one particular value

within this range as the most reasonable value in light of all the relevant

evidence and based on considerations of fairness.”

Still, such

humility looks hollow when expert witnesses and judges use a single,

fraught, technique. Bankers with their more circumspect, holistic approach

to valuation offer a lesson to the professors and the courts who rely upon

them.

sujeet.indap@ft.com

|

© The Financial Times Ltd 2016 |