Business Day

BlackRock Wields

Its Big Stick Like a Wet Noodle on C.E.O. Pay

Fair Game

By

GRETCHEN

MORGENSON

APRIL

15, 2016

|

TimesVideo |

|

|

|

Laurence Fink, chief

executive of BlackRock, explains why earnings declined for the

world’s largest asset management firm.

By CNBC on Publish Date April 14, 2016. Photo by CNBC.

|

For several years, Laurence D. Fink, chairman and chief executive of

BlackRock, the money management

giant, has been on a

crusade, exhorting corporations

to change their short-term ways. Executives should forgo tricks that

reward short-term stock traders, he argues, like share buybacks

purchased at high valuations. Instead, corporate managers should focus

on creating value for long-term shareholders.

It’s an

admirable argument that has won Mr. Fink wise-man status on Wall Street and

accolades in the press. Hillary Clinton has echoed his ideas on the campaign

trail.

| |

Fair Game

A

column from Gretchen Morgenson examining the world of finance

and its impact on investors, workers and families

See More »

|

| |

|

Certainly, as the head of

BlackRock, Mr. Fink wields an

outsize stick. With $4.6 trillion in assets and ownership of shares in

roughly 15,000 companies, BlackRock is the world’s largest investment

manager.

But if Mr. Fink

really wants to get the attention of company executives on stock buybacks and

other corporate governance issues, why doesn’t BlackRock vote more often against

C.E.O. pay packages of companies that play the short-term game?

Executive compensation is inextricably

linked to the shareholder-unfriendly actions Mr. Fink has identified; voting

against pay packages infected by short-termism would help curb the problem.

But BlackRock

rarely takes such a stance. From July 1, 2014, to last June 30, according to

Proxy Insight,

a data analysis firm, BlackRock voted to support pay practices at companies 96.2

percent of the time.

On pay issues,

anyway, Mr. Fink’s big stick is more like a wet noodle.

BlackRock’s

“yes” percentage runs far higher than that of other money managers that express

concern about corporate responsibility.

Domini Funds supported pay practices only 6

percent of the time during the period, while

Calvert Investments did so at 46 percent of

companies.

Public pension

funds are also big on rejecting pay policies, Proxy Insight said. Since 2011,

the State Universities Retirement System of Illinois has voted no 63 percent of

the time while the city of Philadelphia rejected 52 percent of pay policies it

voted on.

|

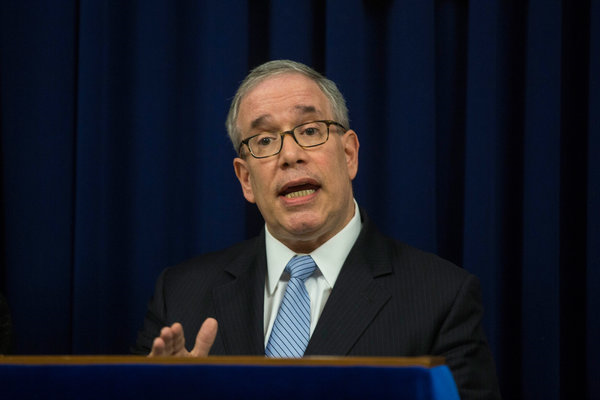

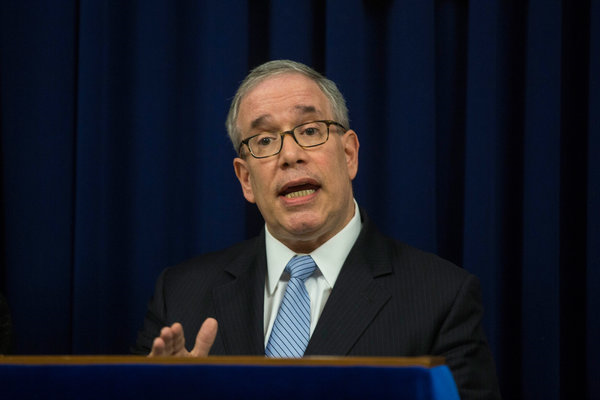

Funds overseen by Scott

M. Stringer, comptroller of New York City, voted against company pay

practices 33 percent of the time.

Credit Hiroko Masuike/The

New York Times |

Scott M. Stringer, the New York City

comptroller, said that in the 2015 proxy season, the five pension funds under

his oversight have voted against pay practices 33 percent of the time. He added

that his funds voted their shares directly “to avoid the risk that money

managers may cast proxy votes that aren’t aligned with the long-term interests

of our beneficiaries.”

“This is

especially true,” Mr. Stringer added, “when it comes to votes on executive pay,

political spending disclosure and climate risk.”

It’s true that

BlackRock’s voting record is not much of an outlier compared with some other big

money managers’. Fidelity Funds, known for keenly supporting corporate

management in its proxy voting, said yes on pay 96 percent of the time, Proxy

Insight said. Vanguard’s most recent record was to support 95 percent of pay

practices; Putnam Investments did a bit better, voting yes on 93 percent.

But none of

these firms’ chief executives have taken up the public fight against short-termism

that Mr. Fink has.

Even at

companies that have made big repurchases of their shares in recent years,

including Yahoo, General Electric, Home Depot and IBM, BlackRock has voted yes

on pay. BlackRock also supported the pay policy under fire at Valeant

Pharmaceuticals International, the crippled drug maker.

Ed Sweeney, a

BlackRock spokesman, provided this statement: “Executive compensation that is

disconnected from company performance is a symptom of broader governance

failures. When governance issues are identified in companies, we’ve found that

engaging with senior management and directors is the most effective way to

catalyze change.”

Last year, he

added, the firm “engaged with approximately 700 companies in the U.S. and

executive compensation was a focus of 45 percent of those meetings. If we

determine that issues will not be remediated through engagement, we vote against

specific proposals as well as the directors on related committees.”

But

Stephen

Silberstein, a retired software company founder and a BlackRock investor, isn’t

buying this argument. So he wrote a shareholder proposal addressing BlackRock’s

record on pay that the firm’s stockholders will vote on at their annual meeting

on May 26.

The proposal

would require BlackRock’s board to issue a report to shareholders by December

that “evaluates options for bringing its voting practices in line with its

stated principle of linking executive compensation and performance, including

adopting changes to proxy voting guidelines, adopting best practices of other

asset managers and independent rating agencies, and including a broader range of

research sources and principles for interpreting compensation data.”

In an interview,

Mr. Silberstein told me why he focused on BlackRock: because it’s huge, its

record on pay votes is bad and he is a shareholder. “I’ve been interested in

income inequality for quite some time,” Mr. Silberstein said. “On the bottom

end, it’s raising the minimum wage and on top end, it’s reducing the pay of

C.E.O.s.”

Perhaps

BlackRock hesitates to call out other chief executives on their pay because of

Mr. Fink’s own compensation, which is lush. In 2015, he received $26 million, an

8 percent increase from the previous year; BlackRock’s net income, meanwhile,

rose just 2.7 percent during that period.

In his annual

letter to shareholders, Mr. Fink said his

firm believed “in a pay-for-performance culture, aligning employee incentives

and compensation with company-level performance.”

As You Sow, a nonprofit organization that

promotes shareholder advocacy, disagrees. In a recent

study, it concluded that Mr. Fink was the

39th-most-overpaid chief executive among 100 large companies.

Mr. Silberstein

says he knows his is an uphill battle. Nevertheless, he is hopeful that

shareholders will vote for his proposal. “I’m going and talking to every pension

fund financial manager I can see,” he said.

Mr. Fink has

done a service by highlighting corporate activities that compromise the

potential for long-term shareholders’ prosperity. This is an important

conversation to have.

But talking the

talk is one thing, walking the walk another. Why not lead the parade, BlackRock,

instead of merely waving from the sidelines?

A version of this article appears in print on April 17, 2016, on page

BU1 of the National edition with the headline: Wet Noodle Where a

Stick Ought to Be.

© 2016 The

New York Times Company