Business Day

A Simple Test to

Dispel the Illusion Behind Stock Buybacks

Fair Game

By

GRETCHEN

MORGENSON

AUG.

12, 2016

|

A trader at the New York

Stock Exchange in June. As shares have climbed, so have the prices

companies pay to buy back their stock.

Credit Lucas Jackson/Reuters

|

Stock

investors have had one sweet summer so far watching the markets edge

higher. With the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index at record highs and

nearing 2,200, what’s not to like?

Here’s

something. As shares climb, so too do the prices companies are paying

to repurchase their stock. And the companies doing so are legion.

Through July of

this year, United States corporations authorized $391 billion in repurchases,

according to an analysis by

Birinyi Associates. Although 29 percent

below the dollar amount of such programs last year, that’s still a big number.

The buyback beat

goes on even as complaints about these deals intensify. Some critics say that

top managers who preside over big stock repurchases are failing at one of their

most basic tasks: allocating capital so their businesses grow.

Even worse,

buybacks can be a way for executives to make a company’s earnings per share look

better because the purchases reduce the amount of stock it has outstanding. And

when per-share earnings are a sizable component of

executive pay, the motivation to do

buybacks only increases.

| |

Fair Game

A

column from Gretchen Morgenson examining the world of finance

and its impact on investors, workers and families

See More »

|

| |

|

Of

course, companies that conduct major buybacks often contend that the

purchases are an optimal use of corporate cash. But

William Lazonick, professor of

economics at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, and co-director

of its Center for Industrial Competitiveness,

disagrees.

“Executives who get into that mode of thinking no longer have the

ability to even think about how to invest in their companies for the

long term,” Mr. Lazonick said in an interview. “Companies that grow to

be big and productive can be more productive, but they have to be

reinvesting.”

Broadly speaking,

those reinvestments appear to be in decline. Indeed, economists are concerned

about the comparatively low levels of business investment since the economy

emerged from the downturn more than seven years ago. This phenomenon may be

attributable in part to the buyback binge.

One of the best

arguments against stock repurchases is that they offer only a one-time gain

while investing intelligently in a company’s operations can generate years of

returns.

This is the view

of Robert L. Colby, a retired investment professional and developer of

Corequity, an equity valuation service used

by institutional investors.

“The simplest way

to evaluate a company’s asset allocation decisions over the years is to see

whether its net profit growth is close to its earnings-per-share growth,” Mr.

Colby said. “Unlike an investment in the business, share buybacks have no effect

on net profit and there is no compounding in future years.”

Mr. Colby has

developed an illuminating analysis that identifies a crucial difference between

many truly successful companies and their underperforming counterparts. The

exercise highlights the growth mirage that buybacks have on earnings-per-share

measures. In addition, it shows that returns on investment need not be that

large for a company to generate growth rates exceeding the evanescent

earnings-per-share gains associated with buybacks.

In his test, Mr.

Colby compared net profit growth and earnings-per-share gains at pairs of

companies in the same industries from 2008 through 2015. In each case, he

contrasted a company that bought back loads of shares during the period with

another that did not.

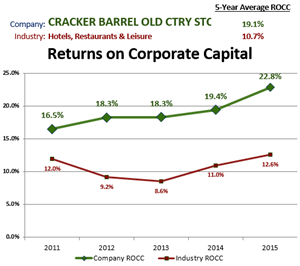

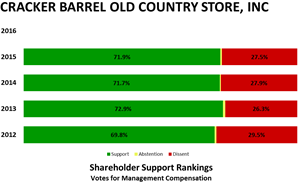

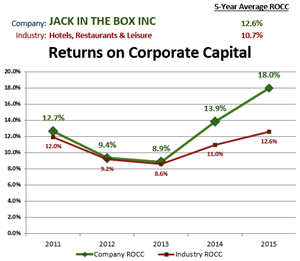

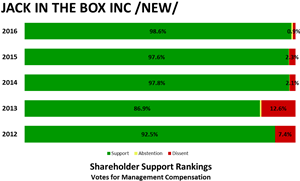

One

case study examined

Cracker Barrel Old Country Store and

Jack in the Box, two restaurant chains.

Cracker Barrel bought back only $160 million worth of shares over the period

while Jack in the Box repurchased $1.2 billion, reducing its share count by 37

percent.

Cracker Barrel

passed the net profit test ably: Its growth in earnings per share over those

years was 13.6 percent a year while its net income grew at a virtually identical

14 percent.

Jack in the Box

made quite a contrast. Its annual earnings per share rose by 6 percent over the

period, but its net profit declined by 0.5 percent a year.

To bring its net

profit to the level of growth it showed in per-share earnings, Mr. Colby said,

Jack in the Box would have had to generate after-tax returns of only 4.8 percent

on the $1.2 billion it spent buying back shares. That doesn’t seem

insurmountable.

Linda Wallace, a

spokeswoman for Jack in the Box, said the company’s business model generated

significant cash flow, “which our shareholders have told us they prefer to be

returned to them in the form of share repurchases and dividends.”

She added that the

average price the company paid to buy back its stock during the period was just

under $37 a share, well below Friday’s closing price of $98.93.

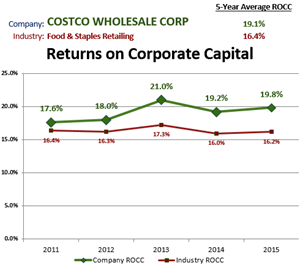

Another notable

buyback comparison was between

Costco and

Target, two large discount retailers. While

Costco spent $2.7 billion to repurchase shares from 2008 through 2015, Target

allocated $11.4 billion, reducing its share count by 20 percent.

Costco’s annual

earnings-per-share gains of 9 percent during the period were almost identical to

its 8.9 percent net profit growth.

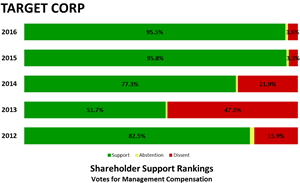

Target’s numbers

tell a different story. On the strength of its repurchases, Target’s earnings

per share rose by 7.3 percent each year. Its annual net profit growth was just

4.3 percent, Mr. Colby found.

To close that gap,

Mr. Colby calculated the after-tax investment returns Target would have had to

generate on the $11.4 billion it spent on buybacks. The answer was a

surprisingly nominal 5 percent.

Erin Conroy, a

Target spokeswoman, said the company’s capital allocation priorities focus on

“growing long-term shareholder value and supporting our enterprise strategy.”

She cited Target’s practice of annual dividend increases and said that last

year, the company added an infrastructure and investment committee to its board

to provide more oversight of investments.

Testing for the

buyback mirage is a worthwhile exercise for investors. That’s why it is the

topic of a new program at

the Shareholder Forum, which convenes

independent workshops to provide information to help investors make sound

decisions.

The net profit

test, said Gary Lutin, a former investment banker who heads the forum, “cuts

through to the essential logic of comparing a process that grows a bigger pie —

reinvestment — to a process that divides a shrunken pie among fewer people:

share buybacks.

“It’s pretty

obvious,” he continued, “that even mediocre returns from reinvesting in the

production of goods and services will beat what’s effectively a liquidation

plan.”

Investors may be

dazzled by the earnings-per-share gains that buybacks can achieve, but who

really wants to own a company in the process of liquidating itself? Maybe it’s

time to ask harder questions of corporate executives about why their companies

aren’t deploying their precious resources more effectively elsewhere.

A version of this article appears in print on August 14, 2016, on page

BU1 of the New York edition with the headline: Dispelling the Illusion

Behind the Buybacks.

© 2016 The

New York Times Company