Business Day

The Trump Effect on

C.E.O. Pay

Fair Game

By

GRETCHEN

MORGENSON

MAY

26, 2017

|

TClockwise from top left: Jamie

Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, Steve Ells of Chipotle Mexican Grill,

Gerald L. Hassell of Bank of New York Mellon and Dinesh C.

Paliwal of Harman International Industries.

Clockwise from top left: Mario Tama/Getty Images; Stephen

Brashear/Associated Press; SeongJoon Cho/Bloomberg; Kim Hong-Ji/Reuters |

After

the November election, the stock market experienced a Trump bump. The

surge in share prices thrilled investors, but some corporate

executives had even more reason to celebrate. That’s because rising

prices can fuel higher pay even if other corporate results are so-so,

which seems to be the case for some companies right now.

Consider

Equilar’s rankings of the

top 200 highest-paid C.E.O.s,

compiled for The New York Times. The company in the middle of the list

awarded its C.E.O. $16.9 million, 9 percent more than it did in 2015,

even though median revenues increased only 3 percent.

Total shareholder

returns were explosive — up 14 percent for the median company. A close look at

the numbers suggests that the levitating 2016 stock market was a powerful driver

of C.E.O. pay last year, and the bull market seems to have made shareholders

less likely to complain about the pay increases executives received. Yet there

are serious questions concerning the ties between

executive pay and a company’s stock

performance.

Corporate

compensation committees typically consider stock performance when determining

pay. Another

study by

Equilar, a compensation analysis company in

Redwood City, Calif., found that 57.4 percent of all Standard & Poor’s 500-stock

index companies used total shareholder return, which includes dividends, as a

performance measure for compensation purposes in 2015.

| |

Fair Game

A

column from Gretchen Morgenson examining the world of finance

and its impact on investors, workers and families

See More »

|

| |

|

But calibrating how much weight a stock price should have on C.E.O.

pay is tricky: A company’s stock price can be influenced by share

buybacks and other financial engineering that does little to produce

long-term value. Why reward a C.E.O. for that?

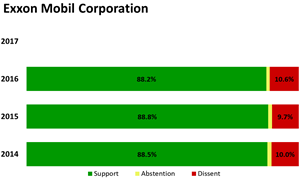

And

sometimes a company’s stock price rises for reasons that are unrelated

to its operating performance. Remember when oil prices were hitting

the stratosphere a decade ago? Executives at companies like

Exxon Mobil reaped enormous pay

awards not just because of able

leadership but also because the escalating value of the commodity

propelled the prices of their stocks.

Something similar

may have happened after last year’s presidential election. Call it the Trump

effect on C.E.O. pay.

By early November,

many stocks were barely up on the year — the S.&P. 500 had eked out a mere 2

percent gain. But after the election, the overall market rallied on expectations

of the incoming Trump administration’s pro-business agenda. The S.&P. 500 wound

up almost 10 percent higher for 2016.

For an outsider,

determining precisely how a company assesses a performance metric is difficult,

of course. But the lift from the Trump effect seems to have been most pronounced

among industries in which investors believed the administration’s deregulatory

fervor would be greatest and thus lead to lower costs and more profits.

The financial

arena is a prime example. Throughout most of 2016, the S.&P. Financial Select

Sector Index bounced around a narrow range, essentially trading flat on the

year. But it took off after the election, soaring to a 20 percent gain by year’s

end. Investor assumptions that the new administration would roll back the

Dodd-Frank Act and generally reduce restrictions on financial activities powered

this move.

There are 31

finance executives on Equilar’s highest-paid C.E.O. list for 2016. Over half of

them — 17 — got raises last year, and each of the 17 companies used shareholder

returns as a metric in determining their pay. Ten of those C.E.O.s received

double-digit increases.

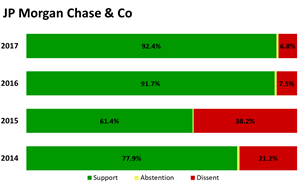

The highest-paid

finance executive was Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of

JPMorgan Chase. His total compensation was

$27.2 million, nearly a 50 percent increase from the $18.2 million he received

in 2015, according to Equilar.

In the top 200

rankings, Equilar relied on standard compensation figures required in proxies by

the Securities and Exchange Commission. JPMorgan supplied those figures, but in

another section of its proxy, it listed Mr. Dimon’s pay as $28 million in 2016

and $27 million in 2015, so according to the financial firm, Mr. Dimon’s pay

increased by just $1 million, or nearly 4 percent.

In detailing Mr.

Dimon’s pay, the proxy noted that the bank gained market share in most of its

businesses and generated record net income and earnings per share. The fact that

JPMorgan’s total shareholder return was 35 percent for the year isn’t lost on

investors.

Shareholders seem

relatively content with Mr. Dimon’s package. At the bank’s annual meeting in

mid-May, 92 percent of votes cast approved its pay practices, the same

percentage as last year.

Investors in most

other financial companies did well — only five showed a decline in total

shareholder returns for 2016.

However, while 12

of the finance companies’ shares outperformed the sector stock index, 19 did

not. In spite of this underperformance, 10 of the 19 companies awarded their

C.E.O.s higher pay, and some of the increases were significant.

It looks like a

very sweet game: Heads I win, tails you lose.

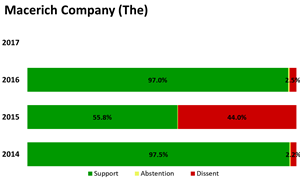

One fortunate

chief executive was Arthur M. Coppola, a co-founder of the

Macerich Company, a real estate investment

trust in Santa Monica, Calif. Although revenues at the company fell 19 percent

in 2016 and its shares lost 9 percent, Mr. Coppola received $13.5 million, a 2.6

percent increase over last year.

Thomas O’Hern,

Macerich’s chief financial officer, said the bulk of Mr. Coppola’s pay consisted

of stock grants with three-year earn-out periods based on the company’s

performance against all public real estate investment trusts. “It’s very

unlikely he would end up earning that amount based on where we are today,” Mr.

O’Hern said.

Shareholders are

scheduled to vote on Macerich’s pay practices on Thursday.

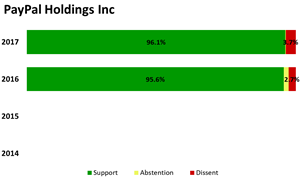

Daniel H. Schulman

at PayPal Holdings is another case in point. He received a compensation package

valued at $19 million, a 31 percent increase over 2015. That pay raise far

exceeded growth rates in the company’s sales, which were up 17 percent, and

earnings and shareholder returns, which both rose around 9 percent during the

year.

Amanda Coffee, a

PayPal spokeswoman, said in a statement, “The majority of Dan Schulman’s

compensation is driven by performance; 2016 was an extraordinary year for PayPal

as we delivered results that exceeded our targets and delivered double-digit

growth across all key metrics.”

At the company’s

annual meeting on Wednesday, 95 percent of the votes cast favored PayPal’s

compensation practices.

To be sure, the

Trump bump didn’t push every company’s shares higher in 2016. As the pay

rankings show, though, even a falling tide lifts the boats of some C.E.O.s.

A total of 44

companies on the list had the same C.E.O. in place in 2015 and 2016 and also had

declining shareholder returns. Yet at 23 of these companies, chief executives

received raises in 2016.

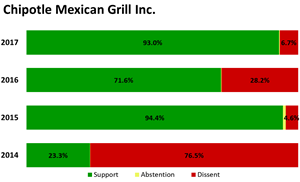

Among the bigger

winners in this group was Steve Ells, the chief executive of Chipotle Mexican

Grill. Even as his company’s revenues fell 13 percent and its shares declined by

21 percent, Mr. Ells snared a 13 percent increase in pay, receiving $15.7

million in 2016.

Chris Arnold, a

Chipotle spokesman, said most of Mr. Ells’s raise last year came in the form of

stock grants. “The 2016 award will not vest and therefore will be completely

without any realizable value,” he said, “unless our stock price reaches an

average of $700 per share for a period of at least 60 consecutive trading days

before February 2019.”

Mr. Arnold added

that a 2013 grant, originally worth $8 million, had no value when it expired in

2016.

Mr. Ells’s

compensation has come under fire from shareholders before; at last year’s annual

meeting, 28.2 percent of the

votes cast opposed Chipotle’s pay practices.

However, during this year’s annual meeting, held on Thursday, votes against the

practices totaled only 6 percent.

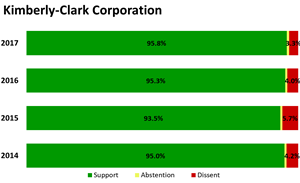

Then there’s

Kimberly-Clark’s C.E.O., Thomas J. Falk. He, too, received a 13 percent increase

in pay, even as sales at his consumer products company fell 2 percent and its

stock lost 7.5 percent.

A Kimberly-Clark

official said that its board believes the most accurate way to measure

longer-term performance is to use multiyear total shareholder returns. “The

company’s three-year return is 24.9 percent and its five-year return is 90.3

percent,” the official said in a statement, “which demonstrates the value that

Kimberly-Clark has delivered to shareholders under C.E.O. Tom Falk’s

leadership.”

Sure enough,

Kimberly-Clark’s shareholders seem content with Mr. Falk’s pay. At the company’s

annual meeting in April, only 3.3 percent of the votes cast opposed its pay

practices.

It’s hard for

investors to think analytically when the market has been rising. That’s

precisely why skepticism about soaring pay is important right now.

A version of this article appears in print on May 28, 2017, on Page

BU1 of the New York edition with the headline: The Trump Effect on

C.E.O. Pay.

© 2017 The

New York Times Company