Business Day

Big Pharma Spends

on Share Buybacks, but R&D? Not So Much

Fair Game

By

GRETCHEN

MORGENSON

JULY

14, 2017

|

Robert U. Ayres, left, and

Michael Olenick found that companies’ heavy reliance on stock

buybacks hurts corporate performance over the long haul.

Roberto Frankenberg for The New York Times |

Under

fire for skyrocketing drug prices, pharmaceutical companies often

offer this response: The high costs of their products are justified

because the proceeds generate money for crucial research on new cures

and treatments.

It’s a

compelling argument, but only partly true. As a revealing

new academic study shows, big

pharmaceutical companies have spent more on share buybacks and

dividends in a recent 10-year period than they did on research and

development. The working paper, published on Thursday by the Institute

for New Economic Thinking, is entitled “U.S. Pharma’s Financialized

Business Model.”

The paper’s five

authors concluded that from 2006 through 2015, the 18 drug companies in the

Standard & Poor’s 500 index spent a combined $516 billion on buybacks and

dividends. This exceeded by 11 percent the companies’ research and development

spending of $465 billion during these years.

| |

Fair Game

A

column from Gretchen Morgenson examining the world of finance

and its impact on investors, workers and families

See More »

|

| |

|

The authors contend that many big pharmaceutical companies are living

off patents that are decades-old and have little to show in the way of

new blockbuster drugs. But their share buybacks and dividend payments

inoculate them against shareholders who might be concerned about

lackluster research and development.

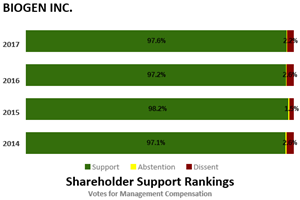

A few

companies have spent more money repurchasing shares than they

allocated to research over the period, the study found. They included

Gilead Sciences, which spent $27 billion on buybacks versus $17

billion on research, and Biogen Idec, which repurchased $14.6 billion

in stock and spent $13.8 billion on research and development.

“The key cause of

high drug prices, restricted access to medicines and stifled innovation, we

submit, is a social disease called ‘maximizing shareholder value,’” the study’s

authors concluded.

This concept, the

authors said, is actually “an ideology of value extraction.” And chief among the

beneficiaries of the extraction are drug company executives, whose pay packages,

based in part on stock prices, are among the lushest in corporate America.

“There’s no

shortage of spending on R&D in the U.S. economy, and no shortage of spending on

life sciences, even though it has declined somewhat in real terms,” one of the

authors, William Lazonick, a professor of economics at the University of

Massachusetts, Lowell, said in an interview. “But there really is very little

drug development going on in companies showing the highest profits and capturing

much of the gains.”

(The other authors

are: Matt Hopkins, Ken Jacobson, Mustafa Erdem Sakinç and Öner Tulum, all

researchers at the

Academic-Industry Research Network, a

nonprofit organization.)

While stock

buybacks appear to be particularly troublesome among drugmakers, big companies

in other industries — in sectors like banking, retail, technology and consumer

goods, among others — are also buying back boatloads of their shares. Through

May, some $390 billion in buybacks have been announced this year, $13 billion

more than at this time in 2016, according to figures compiled by Jeffrey Yale

Rubin at Birinyi Associates, a stock market research firm.

June 28 was the

biggest single buyback announcement day in history. That was when 26 banks

disclosed buybacks worth $92.8 billion, largely a response to having just passed

the stress tests administered by the Federal

Reserve Board. That figure blew past the previous record of $56.4 billion

announced on July 20, 2006.

Many companies

contend that stock buybacks are a great way to return value to their

shareholders. Investors often agree. By reducing the equity outstanding at a

company, the repurchases increase its per-share earnings, often giving a boost

to its stock.

Buybacks made at

low cost can be a fine use of a company’s capital. But when share repurchases

replace a company’s research-and-development spending, that indicates its

management is unable or unwilling to spend on innovation that could generate

future earnings to shareholders.

As the buyback

binge continues, another new academic study shows, a heavy reliance on them

actually hurts corporate performance over the long haul. These researchers found

that the more capital a business invests in stock repurchases based on its

current market capitalization, “the less likely that company is to experience

long-term growth in overall market value.”

“Secular

Stagnation” is by Robert U. Ayres, emeritus professor of economics, political

science and technology management at the global business school Insead, and

Michael Olenick, a research fellow there. It compares the performance of

companies that lean heavily on buybacks with those that do not.

Spending money on

buybacks and dividends has increased among United States companies from

negligible levels in the 1980s, the researchers said, to 38 percent of earnings

in 2000. By 2011, buybacks had grown to 79 percent of earnings, rocketing to 110

percent in 2015.

The

research looked at 1,839 large company

buybacks from January 1990 through last month, examining 6,516

inflation-adjusted transactions. The academics then examined the amounts these

companies had spent on repurchases compared with their current market

capitalizations.

Mr. Ayres and Mr.

Olenick found that 199 companies repurchased shares equal to at least half their

current value. Some 64 companies spent over 100 percent of their current market

capitalization on buybacks.

When the academics

combined these companies’ current market values with the amounts they had spent

on buybacks, the sum showed what the companies should have been worth if they

had invested the money in a money-market account instead.

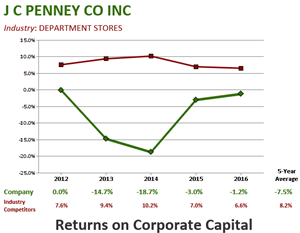

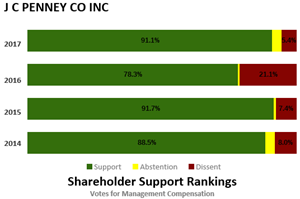

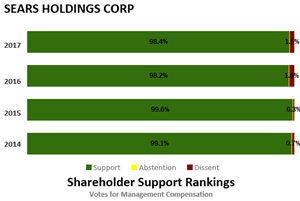

Fifty companies

have spent more inflation-adjusted capital buying back stock than their

businesses are currently worth in market value, the study found. Companies on

this list include HP Inc., J. C. Penney and

Sears Holdings.

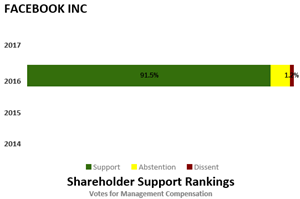

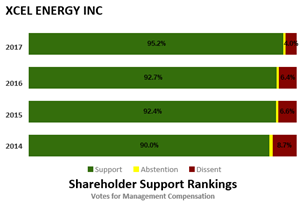

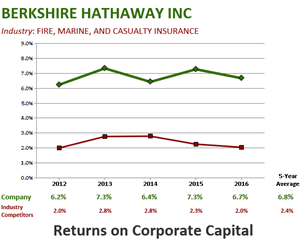

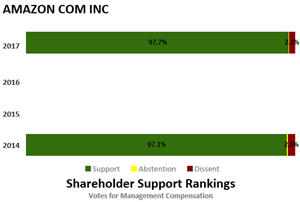

By contrast, the

research identified 269 strong performers that have repurchased stock worth just

2 percent or less of their current market values. They include

Facebook, Xcel

Energy, Berkshire Hathaway and Amazon.

Company executives

who buy back large numbers of shares instead of investing in their businesses

are committing corporate suicide, Mr. Olenick said. “When managers can’t create

value in the business other than buying their own stock,” he said in an

interview, “it seems like it’s time for a management change.”

His co-author, Mr.

Ayres, said he suspected the buyback craze was rooted in executives’ laser focus

on short-term results. “They have short-term expectations,” he said in an

interview. “They’re in their jobs for a few years at most; they’re not really

interested in the long-term future of the company.”

Share buybacks

provide immediate gratification, the stock market equivalent of a sugar high.

That makes them alluring in the short term. Until the crash that usually

follows.

A version of this article appears in print on July 16, 2017, on Page

BU3 of the New York edition with the headline: When Big Pharma Spends,

Research Isn’t No. 1.

© 2017 The

New York Times Company